Transcending Cornpone in the God-Haunted South: A Conversation with Cleanth Brooks

Originally published as “A Partisan Conversation: Cleanth Brooks” in Southern Partisan 3.2, Spring 1983, pp 22-26.

“It was an eight o’clock class, that excruciating hour designed to separate true acolytes from dilettantes. Mr. Cleanth Brooks, co-author of Understanding Poetry, on which my generation cut its critical teeth, was almost always there in the classroom before the first of us, a short, round-faced man whose eyes blinked from behind thick lenses and who stooped forward as he walked so that his astonishingly tiny feet seemed always to be trying to catch up to his center of gravity. He was dapper. The leather of his Oxfords shone, his charcoal gray flannels held a knife’s edge crease, and his brown, herringbone Harris tweed jacket was cut with the insouciant perfection of the great Ivy League haberdashers. Only his ties were on occasion rebellious, a reminder of the West Tennessean blood that coursed beneath his exquisite manners.

They distinguished him then as they do today. In that musical Mississippi accent, he revealed to us the disciplines of rhythm, language, and imagery that, when perfectly harnessed, can produce the magic of a poem. In suggesting his reading of, say, a sonnet by Yeats, he shunned any semblance of imposing it. He would begin, ‘On . . . the one hand,’ presenting his view, followed inevitably, by, ‘On . . . the other hand,’ presenting an opposing, or different, view. (As he grew older, we, his ex-students, grinned to hear him begin, ‘On . . . the other hand,’ so tender and scrupulous had he become about the opinions of others.) He was so fair, his enunciation so gentle, his manner so mild, that one can easily miss the steely analytical faculties that have established Cleanth Brooks as possibly the most rigorous as well as one of the most sensitive of the so-called (he doesn’t much cotton to the label) ‘New Critics.’

At Yale, his kindness was legendary: he read all our poetical efforts, spending precious hours in his Davenport College office (ever so gently) criticizing them. Among his greatest contributions to literature may be that he taught most of us so well to distinguish between the good and the not-so-good that clods like myself finally desisted in our assaults on the Muse. If you come upon The Well Wrought Urn, A Shaping Joy, or his two masterful works on William Faulkner, or, perhaps, a tattered and much-marked old copy of Understanding Poetry, treat yourself to a revolution—and marvel at the worth of a man who at age 75 is still teaching us that the only intellectually reputable reaction to emotionally tendentious works like Ode To The West Wind is a horse laugh.” — Reid Buckley

PARTISAN: How much is the South changing? You have argued that the South has remained unchanged in fundamental ways. I believe you cite John Shelton Reed to support your view that the South enjoys a certain stability in attitude toward family. religion, place and history. In fact, you have suggested that the South is becoming even more different and distinct . . .

BROOKS: Yes. That’s what Reed says. I can’t vouch for it, and I’m wary of sociologists generally. But Mr. Reed is one who writes the King’s English literately. And he’s come up with some surprising conclusions. Certain things in the South are changing surely. We have to admit to the growth of airports, skyscrapers, Holiday Inns, national advertising, radio and television shows. But Reed claims that, as you burrow down a little beneath those, you will find the more basic differences—differences in attitude, language and custom—these things are actually defining themselves more accurately.

PARTISAN: But you say you’re not sure–that you can’t vouch for it?

BROOKS: Well, I’ve sojourned for so long in New England. When I come back, it’s like coming home. Yet, many of my Southern friends say, “Oh Cleanth, it’s all changing. It’s all changing.” I think they’re wrong. But then, I could be wrong.

PARTISAN: In The Dispossessed Garden, Lewis Simpson speaks of the Southern writer’s “covenant with memory and history.” Are Southern writers today further removed from those circumstances that shaped great literature?

BROOKS: Lewis Simpson worries about that more than I do. But he is a first-rate observer. So we have to take his concern seriously. I think this: the Southern writer today is going to have to write in a different way from Faulkner and other Southern writers of the 1930s and 40s—for obvious reasons.

The South can remain the South without being static. There will be shifts. Scotland, for example, has certainly retained a sense of being a separate nation from England in spite of close ties. You even have an Archbishop of Canterbury who’s a good Scot and Scottish Prime Ministers running the government in London. Even so, the Scots have kept a sense of their own distinctness.

The Southern writer today who is 40 years old cannot talk to his Confederate soldier grandfather, as Faulkner could. The fact that the South must alter doesn’t mean that the South will stop being a particular region. In fact, I don’t want the South to endure on a pure cornpone diet just to save ancient glory and pride. I want us to prosper. Yet prosperity brings its own dangers. New Orleans, for example, is rapidly ruining itself as a city: one great hotel after another overshadowing the French Quarter. Any city or region which goes pell-mell to attract tourists is inviting trouble.

PARTISAN: If the shaping experience of the generation of Faulkner was the War Between the States and Reconstruction, what are the shaping experiences of modern Southern writers? The 1954 Brown decision?

BROOKS: Even today, the Southern writers that seem to me ablest and best are the ones who still write with knowledge of the country people—white or black—small town, the sense of family and community. Even when they are describing the tragic experiences of families dissolving, communities going to pieces, they see it as something tragic. They don’t take it simply as the way the world wags.

PARTISAN: That’s true. And you know I have never sensed a generation gap in the South. The generation gap was bridged by the grandfather and grandchild sitting around the campfire on those hunting trips where you never hunt at all, just sit around and barbecue and swap yarns.

BROOKS: I can see that. All my family were hunters and fishermen of one sort or another. We all had this unifying tradition.

PARTISAN: Talk about hunting will be absolutely horrifying to certain literary circles in New York City. They associate the South with the brutality of “Easy Rider.” You and Mr. Warren deplore what you call the “frontier unruliness and violence”1 in the South. Part of this is associated with deer hunting, and so forth. But what would Faulkner, Lytle, Warren and the others have done without the new material that this violence permitted them to use?

BROOKS: I think all of the writers you named were brought up in that tradition, and they used it in their work. Some people have trouble accepting it. I taught a course in British and American literature at Yale. I caught the point fairly early. I would say to my class, you are going to read a great hunting story. How many of you have ever hunted at all? There might be one hand in the class. I’d tell them: you’ve got to get over the idea that a hunter is a sadist or a brutal man. Otherwise, you won’t be able to read one of the finest stories ever written, Faulkner’s Go Down, Moses.

PARTISAN: The stories of violence have their bad parts, but they also indicate a deeper humanity . . .

BROOKS: I agree. You don’t want to kill the hope that we can discipline the violence. We know we will never be able to do it completely, but we certainly don’t want to kill the humanity which is along side of it.

PARTISAN: Is there, in the South, a corrective to this problem? The persisting tradition of manners in the South; the taxi driver who brought our bags into the hotel instead of leaving them on the curb, as would have happened in other places; the Southerner of all economic classes who says, “Yes Sir” and “Yes Ma’am” to his parents; the courtliness of husbands toward their wives—all of those things so unfashionable today in other regions. Is this not a control over violence?

BROOKS: Yes. Allen Tate has written extensively on that subject. [Robert Penn] Warren too. If you call somebody an SOB, you’d better smile or make it perfectly plain that this is a joke and not meant. If you mean it, there will be hell to pay. So you use the lubricant of good manners, courtesy, “Thank you,” “Yes Sir,” “No Sir.” You use the civilities because honor, even the poorest man’s honor, is pretty tender. If he gets the idea that you are trying to insult him, watch out! You may have a real fight on your hands. This is where good manners are not simply a kind of elegant embroidery on the social scheme because everybody is being prissy. It’s a very necessary way to help keep things under control.

PARTISAN: Do you realize what you are saying? You are really horrifying a lot of people with what you just said.

BROOKS: Yes, sure, I know.

PARTISAN: If I may move on to something else? Can you explain the continuing flight of Southern intellectuals from the South? You spent thirty years up north; Mr. Warren spent many years up north; Tate spent many years away from the South before returning . . .

BROOKS: I can answer for myself and make some guesses about a few others. It was a standard joke at Yale that Mississippi was the state lowest on the rung of educational and economic statistics. And yet it is a curious thing that Mississippi is producing more writers and fewer readers of books than any other place in the country. I used to tease my classes by pointing out that we live in this nice well-built, sanitized, high-income state of Connecticut. But name me a native son or daughter of Connecticut who is a writer. Who are they? I couldn’t find any. Maybe there is a moral to this.

But, to get back to your question. Very frankly, I left LSU and the South because the Southern Review was killed. Both Warren and I left when other schools, which happened to be in the north, gave us offers. Warren went to the University of Minnesota and I went to Yale. I had a very decent friend who was the head of my department. He did all he could with the administration. They jacked-up my salary, they thought a great deal, and it was still $1500 under my other offer. At the time, due to certain family problems, I needed the money badly. And keep in mind that the spending power of money was much greater 50 years ago than it is today.

PARTISAN: But Mr. Tate spoke so bitterly, or am I misconstruing his words, when he said the South had no place for him?

BROOKS: Well, I know what he means. I would add this: LSU had no place for me. The hierarchy of the university was paying big salaries to the deans in the administration, but they would kill the Southern Review at a time when we were being read at Harvard and in London, and they would not raise my salary at least equal to what I could get elsewhere. So, yes, we were very bitter about it. Vanderbilt did the same thing. They refused Allen Tate a modest graduate scholarship, and they fired Warren eventually. They let [John Crowe] Ransom go at the height of his fame.

PARTISAN: Is this the prophet in his own land having no honor?

BROOKS: Yes, that’s part of it. But now Warren’s name is so honored. Ransom’s name is so honored, Tate’s name is so honored, that anywhere they go in the South, great ovations follow. I had a little part in the Fugitive’s reunion of the 50th anniversary of the publication of I’ll Take My Stand, and the place was packed. Nobody could say too much in favor of them.

PARTISAN: What about today? Who are the new voices you respect as artists, and are they able to make it here in the South?

BROOKS: Well, I think that Reynolds Price is a pretty good novelist. He has a good post at Duke. They want him there. He could go elsewhere if he chose, but he prefers to stay in North Carolina. I understand that Barry Hannan, of whose work I hear such good things, got out of teaching because like many writers, he found the university depressing. But he has chosen to remain in the South. Beth Henley, the young dramatist from Mississippi, has gone to New York, but a playwright has almost got to be on Broadway. There are quite a number who are now staying. In fact, Allen Tate finally came back to the South at the end of his life and lived at Sewanee. He loved it and is buried there.

PARTISAN: So you feel there is no longer this drain of talent?

BROOKS: No. Some of the college administrations are pretty bad, but nearly every college and university in the South has at least one writer in residence. There is a book that came out from a couple of people at the University of North Carolina, an anthology of recent Southern poets. There are over 70 of them in it, and the poems are very good. Most of those poets are living in the South right now. So, yes, the times have changed.

PARTISAN: Cleanth, on another subject, you have written, with hope, that education and the proper schooling will help to preserve certain values. But I always wonder whether that isn’t a forlorn hope.

BROOKS: I think that it is a forlorn hope and I think it’s going to continue to be unless we make what is not likely to happen: a radical change in the whole educational process. We see a few weak gestures that way in the “back to basics” program. But I think the teachers’ colleges have done infinite damage to the teaching process in this country. This doesn’t mean that a great democracy and a relatively wealthy democracy should not provide a good education for everybody who can take it and wants it. I think it should. The truth of the matter is that it hasn’t. Granted, there are exceptions: fine teachers in public schools turn out first-rate people. But on the whole, they are not doing a good job, and the fact that the literacy rate of the United States has been falling steadily for ten years tells its own story. By and large, we are not teaching people to read and write.

PARTISAN: Don’t we now have the illiterate teaching the illiterate?

BROOKS: We do. We have at least two generations of poorly educated teachers. In most states, you can’t teach in public schools unless you have graduated from a teachers college. Teachers colleges have historically emphasized, not content, but method, method, method. So you have people trying to teach mathematics who don’t know mathematics, and you have people trying to teach English who can’t speak or write English.

PARTISAN: And then there’s a related question: what can formal education really accomplish? Can education teach ethics? Can love of the True, the Good, the Beautiful be taught? In a very real sense, isn’t every generation condemned to start from scratch?

BROOKS: I would take a reverse step. There is a sense in which we all start from scratch. Our childhood period and our basic nature are terribly important to us, for good or ill. However, to an extent, you can train people to have an appreciation of the Good, the True, and the Beautiful. You can expose people. Good teaching can expose them to examples and indirectly may give a great deal of instruction. Not by providing formulas for the truth, definitions of the truth. and so on, but by providing models of the true and the good.

We get into a very touchy point here. Public school education in this country is dedicated, for reasons that we all know, to a pluralistic society. We are told: you can’t do this, you can’t do that, you are discriminating against this group or the other. The result is, the public school has been emasculated in a sense. It can no longer teach basic values. For example, how is religion taught in most universities? It’s taught historically and comparatively, which has its own merits. But if you start with an unbeliever, it’s likely to end up making him more skeptical and faithless still.

The public school system and even the great private universities have to respond to a pluralistic world. What you can teach in the way of ethics is very, very little. What you can do, and this is not perfect, but hopeful: you can expose them to the great thinkers and the great artists of the world. It is amazing how hungry college students are, the best ones, for this treatment.

Voegelin2 made one of the most interesting comments along this line that I know. When the great revolt of students occurred in America and Europe during the 1960s, he said, the universities in part had brought it on themselves. Many students thought that they ought to get out of their university life some account of the basic values, something to believe in, something to work for. For various reasons the universities had walked around these things so warily, he said, no wonder young students, uninformed, would blow their tops in this way. They were reacting to the absence of instruction in basic values.

The whole drift of American life is toward the training school, though we like to disguise it under the name of college or university, it’s a place where you go in order to learn how to make a living, learn a skill. Goodness knows, it is an important thing to know how to make a living.

But what used to be and what still ought to be, the real object of humanities, is to teach not merely how to make money, but how to spend it; not merely how to acquire the means for living, but to learn the proper ends. A person who has all the means in the world and doesn’t know what to live for will probably land on a psychiatrist’s couch sooner or later, asking, “What’s it all about? What am I building this fortune for? Why?” American education has been falling down on this business of exhibiting models of the great values of life.

PARTISAN: Plato says the object of education is to make good men. Aristotle spoke of the necessity of teaching people to use their leisure to better themselves. And we know that self-government depends on civic virtue. If civic virtue isn’t taught in our public schools, then we have a situation that militates against a self-governing society.

BROOKS: I agree completely. It’s quite true.

PARTISAN: Turning again to our region, will the South be able to survive the rising tide of polyesterized, three-piece suited, money-grabbing young men who are ignorant of the Southern tradition?

BROOKS: The only good signs I can see are these: I find that in the Southern schools where I have been teaching the brightest, most interested students respond right away. They are genuinely interested in Southern Literature. They are genuinely interested in the tradition dramatized and exemplified in it. They want to learn more about it; they are concerned.

PARTISAN: Now, let me get to the question of alienation applied to the Southern community. We have, all over the South, in TV stations and on radio programs, either yankees or Southerners who are ashamed of their native accent. They adopt the “mid-Atlantic” accent, whatever that is. They are doing their best to get rid of what is Southern about their speech. The common denominator of vulgarities, like a black hole in space, just sucks everything down. How do you protect against that?

BROOKS: I don’t know. How does one protect civilization? How does one protect man’s vision of God? How does one protect the health and vitality of a democratic society? There are no obvious, no easy solutions. It’ll take eternal vigilance and a great deal of faith in the capacity of man. I think there are some specific wrongs that we ought to try to right in education.

As I’ve said, I have very little faith in education as it’s taught. It’s a shambles in many respects. I’ve yet to find a student who, if approached with any vigor and interest, wouldn’t respond to some extent, some with limited talents and some with great talents that have never been touched.

Eric Voegelin made one of the most important, but also one of the most pessimistic, replies to this sort of question. He said, the great problem of any high civilization is to find enough good teachers, enough born teachers to instruct the new generation. He said very few high civilizations ever have enough.

PARTISAN: Then we’re in a bad way. We were talking about the lowest common denominator of our students going into education.

BROOKS: That’s one reason I’m in favor of the private schools. Do all you can to promote private schools. Provide a voucher system so that parents who care about the children can shop around a little. I know what the New York Times says when this is proposed: you will condemn public schools to the worst students; you’ll snatch away the better students. I think there is some merit in that.

On the other hand, I don’t think that people, like the editors of the New York Times, see how bad the situation is already in the public schools. I think public schools need some competition. I think that parents who don’t know much about education when they see how much more progress the children next door are making in private school will either try to get into that school or else raise hell with the public school. Why can’t we get more people doing that?

One of the most stimulating things that I’ve seen was a televised account of an admirable black woman in Chicago who didn’t like the way the schools were being run; so she set up her own school. It’s in one of the poorer districts, and they apparently have to pay a fee. But she can’t take any more students. She has a long waiting list. This is because parents, even those who are uneducated, can see the difference and say, “I want that for my child, too.”

PARTISAN: Yes, parochial schools in the city are filled with non-Catholic blacks. But changing the subject, Cleanth, you say, “Indeed, I shall . . . argue that poetry needs religion, and that the relationship between religion and poetry is a polar relationship in something of the same sense in which we speak of the poles of an electric battery, one positive and the other negative, poles that mutually attract each other and thus generate a current of energy.” Does Robert Penn Warren illustrate your point?

BROOKS: Well, it’s amazing to me how many times God comes up in his poems. He is a seeker; he is a yearner. He knows how important it is and has been for a lot of people in past ages.

PARTISAN: If you don’t mind, I’d like to quote some passages of yours. You say, categorically at one point, that the death of a civilization comes with the decay of religion. A little later on you say, “If one takes a somewhat longer view and believes, one can establish the community again, a truly human community, but do it without reference to transcendental faith.”3

BROOKS: As I get older, and I’m not sure wiser, I am more appalled at the distortions of Christian theology that I find all around me. The people who honestly and so badly misunderstand it, if they could get the scales dropped from their eyes, would say, My God! I didn’t realize. I run into people all my life who think that God was wicked, not even as good as a good human being, to allow his Son to be treated so badly. I think a better knowledge of the Trinity would make them see that it is God Himself sacrificing Himself. I don’t know whether the theologians of my church would accept my view, but I hope they would. Infinite harm has been done in the South by the hot gospelers. But I’ll say this much for them, the South is the only region that still has some hold on the supernatural.

PARTISAN: You call it God-haunted. But going back to the claims of Incarnation, when a poet writes, mustn’t he be aware of that claim, even if he personally rejects it?

BROOKS: I think so. I think my friend Warren has a real appreciation of Christianity, even though it’s detached and not his own

PARTISAN: Which is why he calls himself a yearner.

BROOKS: Yes. He came out of a God-fearing community, by and large. There were wicked people and good people, but I think that it was God-haunted. I know that he has a number of friends who are devout Christians, and he does not scorn them saying. “You of simple faith” or “You of blind faith.” I think the claim of art as religion has been powerful in our time and I can see why, even though I don’t agree with it. I can see why Joyce gave up his Church. How was he going to fulfill himself in what must have seemed to him a rather alienated meaningless universe? He made up his own universe through his work. So does Wallace Stevens, who becomes more and more of a philosophical poet. He can tell you volumes about not only himself but about our age, the artists of our age.

PARTISAN: I have one final question. The church is the custodian of the Word. Over the interpretation of very few words, the Church has suffered through the experience of terrible schisms, bloody wars, torture; the Church has become inhuman and cruel, whether in Geneva or in Toledo makes no difference. So the Church knows personally the importance of the written word. Now explain to me how the Church today can be so cavalier to what it is doing to the Word by its destruction of the euphonics of the language that we were brought up in.

BROOKS: I will simply pound one more mallet head onto the spike you have driven so well. I have spent fifty years trying to teach people the importance of words, getting the right words and putting them together; trying to show how words make drama, plays, novels and poems. The people who are supposed to be guardians of the word sometimes throw all of that away and say, “We can use any old language.”

My feeling is that God will accept any earnest prayer, even if it is given in a sign language. But I’m not worried about God. I’m worried about us. I need all the help I can get in my worship. I want the help of a great language which helps articulate what I have difficulty articulating. More than that, it’s a thing that goes right back to the Jewish origins of the Church. Our sacrifice ought to be the best we can offer. To offer just cheap, shop-worn, everyday language is not good enough when we have something better.

PARTISAN: We find everywhere around us this disrespect for language. In book reviews, nobody pays any attention to the language that the author may have used. They pay great attention to the utilitarian values of the book, either its message or its technical contribution to the craft. But how often have you read somebody who turns around and says, besides which this person writes damn good English. There’s a general rule of indifference to the word.

BROOKS: Well, I used to tell my English students, sometimes in despair, when I thought they felt that they had no important function: “Look, take yourselves seriously. You occupy a castle at the very top of the pass. Everything has to pass your doors. Even the sociology professor is using words; so control the passes if you can; try your best to. In other words, you have got a very important function, and don’t let anybody tell you that you don’t.” THE END

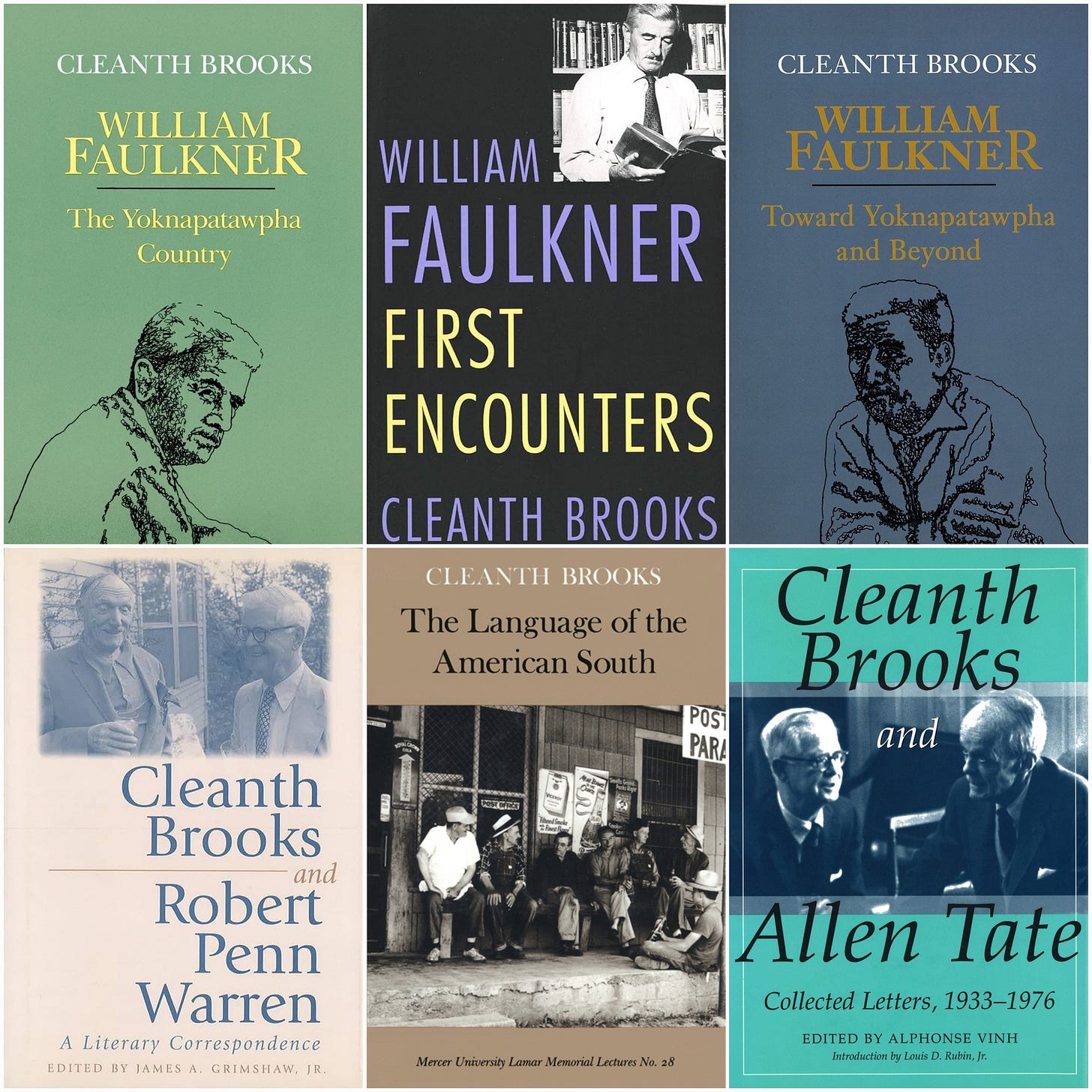

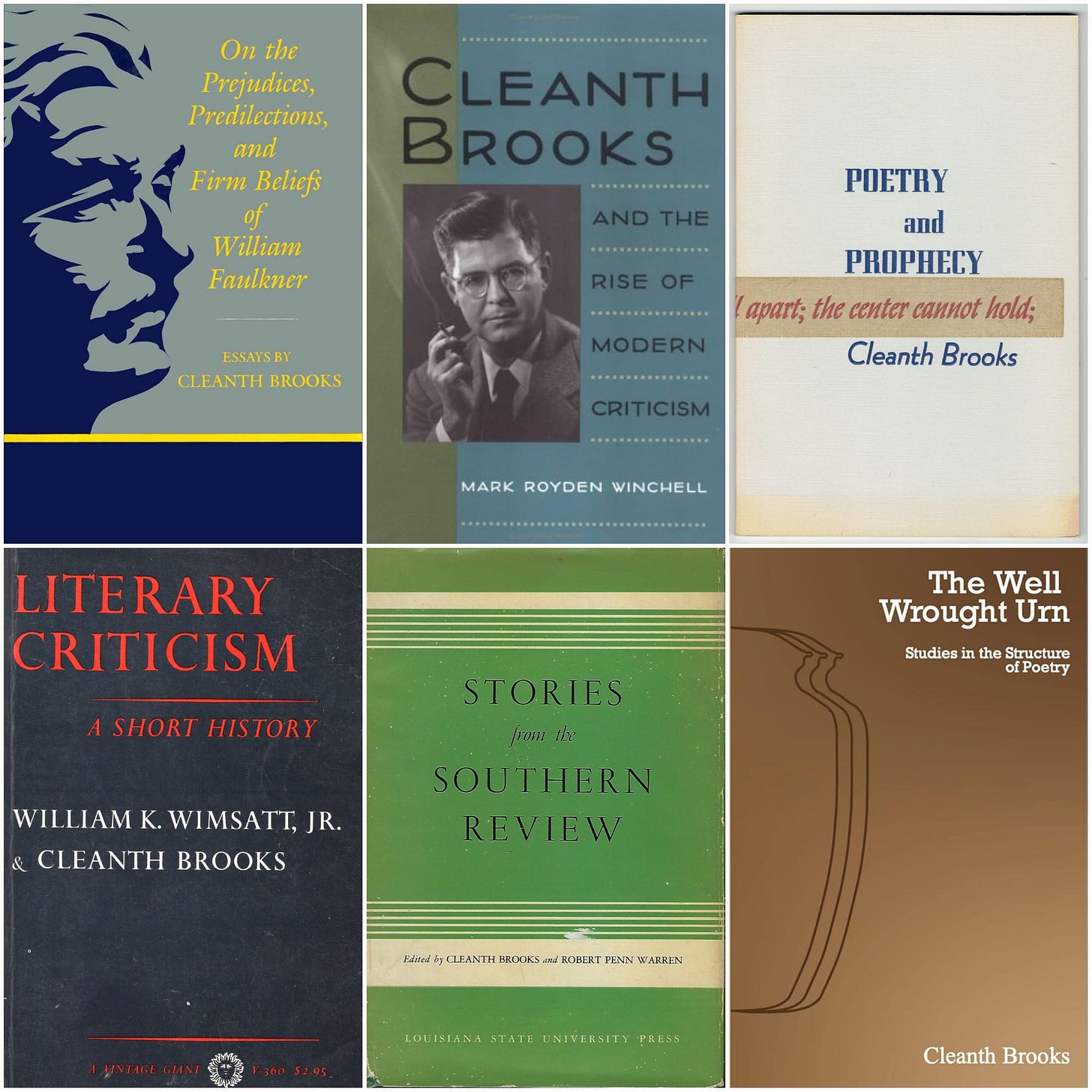

Additional Resources

Video: Cleanth Brooks | Louisiana Legends

Video: Conversation Between Eudora Welty and Cleanth Brooks

Audio recording of Cleanth Brooks delivering a lecture: American Literature, The Past 30 Years.

Audio recording: Conversations on the Craft of Poetry 1: Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren.

Audio recording: Conversations on the Craft of Poetry 2: Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren.

Audio recordings: Soundings Project.

Conversation between Willie Morris and Cleanth Brooks.

Chronicles Magazine search results.

Imaginative Conservative search results.

Digital materials from the Cleanth Brooks Papers at Yale.

Tennessee Encyclopedia entry.

Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame.

“The Well-Wrought Textbook” by Garrick Davis. Humanities, July/August 2011, Volume 32, Number 4.

Open Library results.

Various Cleanth Brooks Articles.

Cleanth Brooks: “Faulkner And The Muse Of History”.

Cleanth Brooks: “The Relation of the Alabama-Georgia Dialect to the Provincial Dialects of Great Britain”.

Cleanth Brook’s chapter from Who Owns America

The Possibilities of Order: Cleanth Brooks and His Work; Chapt. 1, Robert Penn Warren, “A Conversation with Cleanth Brooks.”

Eric Voegelin, author of Order And History, by many deemed the seminal philosopher-historian of this century.

The Possibilities of Order: Cleanth Brooks and His Work.

Once again we thank the Archivist for his generosity.🥃