The Proving Ground

Russell Kirk, Radioactive Soda, and Reading Lists.

In the Utah desert lies Dugway Proving Ground, perhaps the eeriest place I've ever visited. I was there in 2010 for cold weather training before deploying to Afghanistan. During WWII, Russell Kirk spent several years at Dugway, an experience he would later document in The Sword of Imagination:

Of Kirk’s four years in the army, three would be spent here near the heart of the Great Salt Lake Desert — the famous Bonneville salt flats sprawling a few miles to the west of the Dugway camp — surely one of the most desolate and most salubrious spots in all the world. While millions of men were slaughtering one another upon the Ukrainian steppes or in the Papuan jungles, Kirk lay enchanted, like Merlin in the oak, amidst a desert so long dead that it seemed nothing was permitted to die there any longer.

Dugway Proving Ground was then, and is today, the Chemical Warfare Service’s vast experiment field. Aside from conventional spraying of mustard or phosgene gases on goats, to see if such toxic agents would vex the creatures, Dugway became the center for testing two huge deadly experiments: the development of the gel bomb, and the beginnings of bacteriological warfare. Kirk being the only enlisted man at Dugway Proving Ground who possessed a master’s degree, and being an experienced typist, he found himself assigned to duty as recorder and custodian of classified documents — some of them “top secret” indeed. Had Germany and Japan won the war, Kirk might have been put on trial as a war criminal.

On the salt flats the CWS built accurate replicas of German and Japanese villages, to scale and of suitable materials, the houses completely furnished. Dugway Proving Ground possessed a solitary bomber, dispatched now and again to drop gel incendiary bombs upon those villages, in hope they might burn. They did. Having been thus thoroughly tested, the gel bomb was employed, very near the end of the war in Europe, to wipe out Dresden and its population, the air being sucked out of Silesian lungs while their dwellings were incinerated. This had been a war to vindicate the democratic and humanitarian way of life.

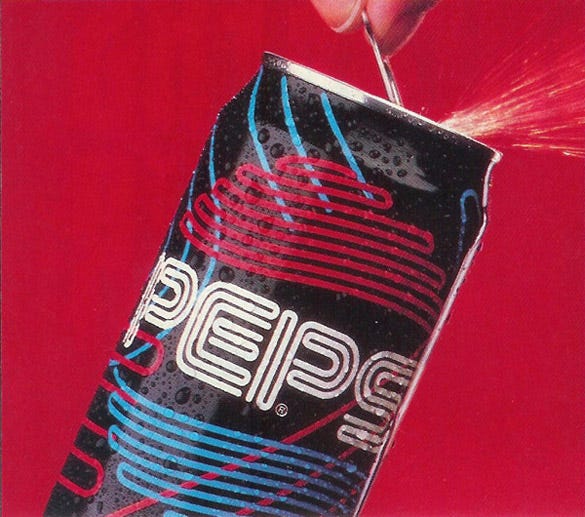

I can’t recall much about the day we found that rusted 55-gallon drum during our training at Dugway. I want to say we spotted it during a little map reading and land navigating. It was February and snowing. That I do remember. The drum was empty except for a pristine MCI, which came after C-rations and before MREs. Stranger still was the empty soda can—no dents, no rust, and older than most of the guys in my platoon. It was the 1990 Neon Pepsi can. I can’t shake the image of it. Months later, on a snow-covered mountain in Afghanistan, I found myself thinking what a beautiful place it was. I began daydreaming, sketching a business plan for a ski resort in the Tangi Valley on the edge of the Hindu Kush stocked with radioactive soft drinks.

Related Reading for the Curious:

Birzer, Bradley J.. Russell Kirk: American Conservative. University Press of Kentucky, 2015. (Probably the best Kirk bio and definitely the most in-depth regarding Kirk’s WWII service.)

Birzer, Bradley J.. “The Mystery of the Utah Desert.” Imaginative Conservative, 2011.

Kirk, Russell “A Conscript in the Desert, Half a Century Ago.” Modern Age, Spring 1993, pp. 272-278.

Kirk, Russell. Imaginative Conservatism: The Letters of Russell Kirk. University Press of Kentucky, 2018. (Contains several letters he wrote from Dugway.)

Kirk, Russell. The Sword of Imagination, Memoirs of a Half-Century of Literary Conflict. William B. Eerdmans, 1995. (Which seems to be out of print, so…)

Chemical and biological warfare is outside my realm, though it has occasioned several exploratory detours. My grasp of World War II is modest at best. However, I'm intrigued by how these and related topics intersect with the South. I’m thinking Camp Detrick, Pine Bluff Arsenal, Redstone Arsenal, Horn Island (and all the military installations in the South, many of which were renamed recently), industrialization, migration, mobilization, Atomic testing, POW camps in the South, Savannah River Plant, environmental impact (e.g. The U.S. Army extensively used sea disposal for chemical agents and munitions, initially dropping loose munitions overboard. In 1946, about 5,000 tons of lewisite munitions were dumped 160 miles off Charleston, SC (Site NC-04). Operation Geranium in 1948 saw another 4,500 tons dumped 300 miles off Florida’s coast (Site FL-02).) There are hundreds, if not thousands, of works on these subjects, and the list below isn’t necessarily an endorsement (many are what you’d expect), but the bibliographies, endnotes/footnotes, etc. will point the way. I’m barely scratching the surface.

A good summary of the history of American Chemical Warfare.

Bolton, Charles C.. Home Front Battles: World War II Mobilization and Race in the Deep South. Oxford University Press, 2024.

Chamberlain, Charles D.. Victory at Home: Manpower and Race in the American South During World War II. University of Georgia Press, 2003.

Daniel, Pete. Toxic Drift: Pesticides And Health in the Post-world War II South (Walter Lynwood Fleming Lectures in Southern History). Louisiana State University Press, 2005.

Drumright, William Wade, “A River for War, a Watershed to Change: The Tennessee Valley Authority During World War II.” PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2005.

Frederickson, Kari A.. Cold War Dixie: Militarization and Modernization in the American South. University of Georgia Press, 2013.

Hagood, Margaret Jarman, 1946. “Farm Population Adjustments Following the End of the War,” Miscellaneous Publications 335394, United States Department of Agriculture

Jaworski, Taylor. “World War II and the Industrialization of the American South.” The Journal of Economic History 77, no. 4 (2017): 1048–82.

Patterson, Robert P.. Arming the Nation for War: Mobilization, Supply, and the American War Effort in World War II. University of Tennessee Press, 2014.

Remaking Dixie: The Impact of World War II on the American South. University Press of Mississippi, 1997.

Robin, Ron Theodore. The Barbed-Wire College: Reeducating German POWs in the United States during World War II. Princeton University Press, 1995.

Roland, Charles P. The Improbable Era: The South since World War II. University Press of Kentucky, 1976.

Scranton, Philip. The Second Wave: Southern Industrialization from the 1940s to the 1970s. University of Georgia Press, 2001.

Sugg, Redding S.. Nuclear Energy in the South. Louisiana State University Press, 1957.

Sunbelt Cities: Politics and Growth Since World War II. University of Texas Press, 2014.

The chapter "World War II and the Command Economy, 1939-1945" in The Takeover: Chicken Farming and the Roots of American Agribusiness by University of Georgia Press, 2017.

The chapter “World War II and the Postwar South” in The New South, 1945-1980 by Numan V. Bartley. Louisiana State University Press, 1995.

The chapter “World War II: The Turbulent South” in The Emergence of the New South, 1913-1945 by George Brown Tindall. Louisiana State University Press, 1967.

The Rural South Since World War II edited by R. Douglas Hurt. Louisiana State University Press, 1998.

White, Gerald Taylor. Billions for Defense: Government Financing by the Defense Plant Corporation During World War II. University of Alabama Press, 1980.

If you want to get really thorough, download and ctrl+f these:

Man, you knocked one right up my alley.