Southern Issues 3: The South, 1958

National Review 1958-03-08

Some years back, I found myself on a private tour through a historic house in South Carolina. The gracious lady hosting us asked a question I hadn’t expected. “What are your thoughts on William F. Buckley Jr.?”

“Ma’am,” I said, after a moment’s reflection, “my leanings are nearer to M.E. Bradford and his camp, and though I respect Mr. Buckley, I never could get comfortable with how some men were cast out, nor how certain events unfolded.” I can’t recall her reply.

Later in the day, an accomplished gentleman privately thanked me for speaking plainly, quietly noting our hostess’s connection to Buckley. The stories of the National Review purges are well-known in certain circles, but the Southern Issue explored here predates those tensions.

The issue at hand, appeared in 1958 as a response to integration legislation, much as the Modern Age issue discussed previously. My purpose isn’t provocation or to editorialize, but to map this publication as one significant coordinate in a complex intellectual topography, one with numerous connections both before and after August 1958.

Those familiar with National Review’s recent ways might be surprised by its earlier stance. Though this territory has been extensively examined, some context seems warranted.1

The Context

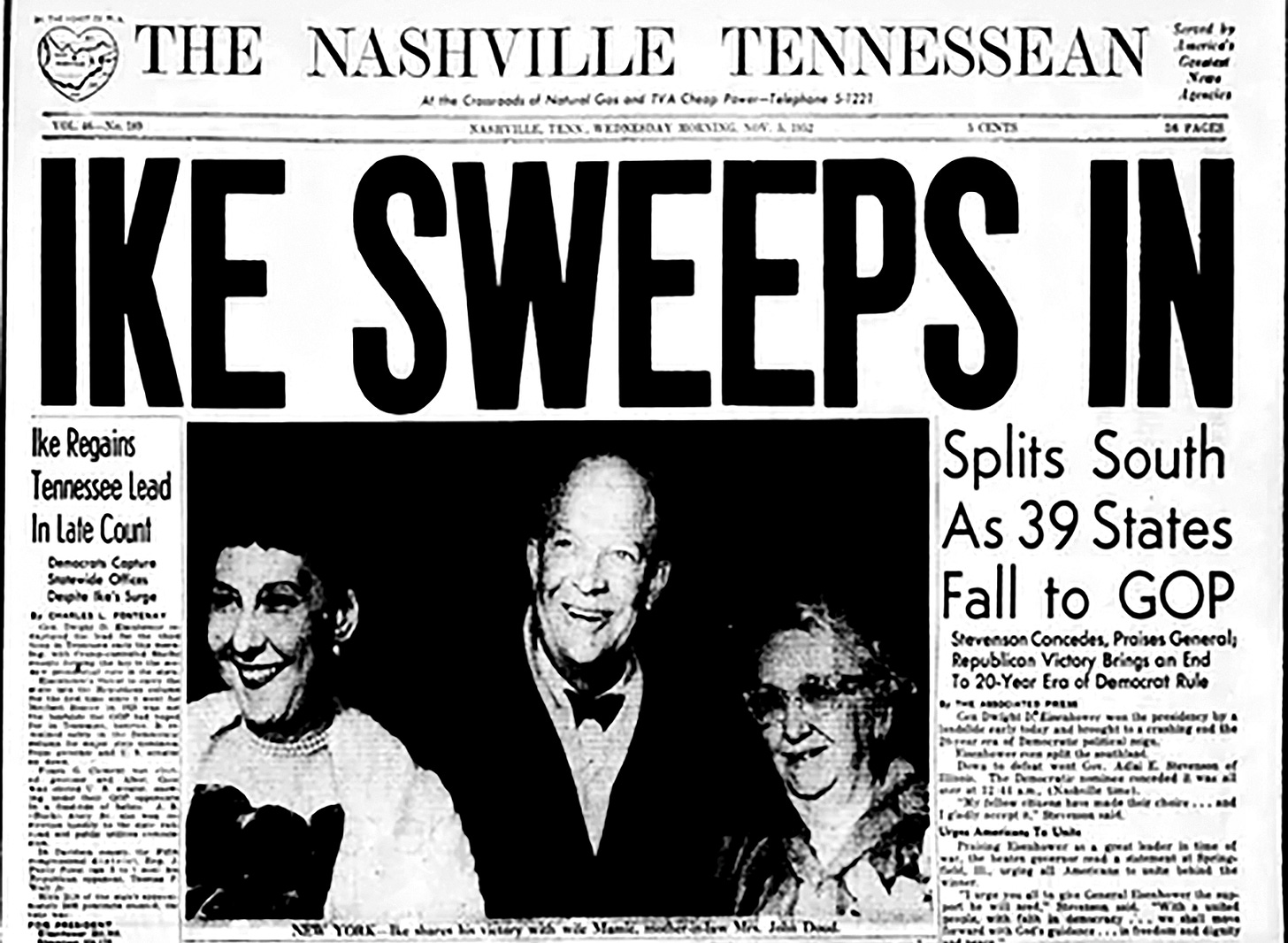

After the 1948 Dixiecrat revolt, Republican strategists saw an opening to remake their party’s fortunes in the South. Eisenhower’s victories in 1952 and 1956 marked real progress in states like Florida, Virginia, and Texas, where a growing white middle class responded to his message of economic restraint and limited federal reach. Yet Eisenhower’s decision to send federal troops to enforce school integration in Little Rock got many Southerners fit to be tied. Still, the GOP pressed ahead with “Operation Dixie,” an initiative aimed at cultivating a new Southern base by recruiting young, college-educated professionals, many with moderately segregationist views.

Beginning in the mid-1950s, National Review (NR) became instrumental in steering the modern Conservative movement southward. William F. Buckley Jr. launched the magazine in 1955 as a bulwark against the centralizing reach of the federal government, against the abstractions of New Deal economics, against Communism’s tentacles. While seeking to forge a unified Conservative voice, Buckley and his editors recognized untapped potential in the South.

Unlike some Republicans, who approached the South cautiously, NR took a more assertive approach. They published sympathetic coverage of Southern resistance to federal desegregation efforts, framing these conflicts not in terms of race, but as battles over constitutional principle and local control. Contributors like Richard Weaver portrayed the South as America’s Conservative heartland, valuing tradition, established order, and community autonomy, qualities NR deemed essential to the broader Conservative vision.

Despite doubts about the Republican Party’s immediate viability in the region, NR initially placed greater hope in Conservative Southern Democrats. Throughout the late 1950s, the magazine consistently presented Southern opposition to civil rights initiatives as part of a legitimate Conservative defense against centralization.

Detour

I never paid much attention to magazine advertisements, until I read Caro’s LBJ biographies. He taught me a few things. You know, follow the money stuff. Several ads in these old National Review issues always piqued my interest—the Milliken ads.

The textile magnate Roger Milliken didn’t just bankroll postwar conservatism, he helped build it. A key player in Strom Thurmond’s party switch, funder of Goldwater and Buchanan’s campaigns, and a major backer of Regnery Publishing, the John Birch Society, and the Manion Forum. He also helped launch National Review. Buckley once called him the magazine’s “most important asset.” Anyway, back to the point.

“Why the South Must Prevail”

Most of the editors had never sweated through a Southern summer. Buckley, however, had lived in South Carolina and his mother was a New Orleans-raised Southern belle, her grandfather a Confederate who bore arms at Shiloh. Early on, NR did have quite the roster of Southern contributors: Donald Davidson, Cleanth Brooks, Andrew Nelson Lytle, Richard M. Weaver, James J. Kilpatrick, Medford Evans, William T. Couch, Sam M. Jones, Robert Y. Drake Jr., J. Fred Rippy, M. Stanton Evans . . .

Relevant NR essays leading up to 1958:

1956-01-18: “National Trends” by L. Brent Bozell.

1956-02-29: “The South Girds Its Loins” editorial.

1956-03-21: “None So Blind . . .” editorial.

1956-04-25: “The Right to Nullify” by Forrest Davis.

1956-05-09: “Southern Discomfort” by Sam M. Jones.

1956-05-23: “Why the South Likes Lausche” by Jonathan Mitchell.

1956-06-06: “Notes from the Gulf Coast” by James Burnham.

1956-08-25: “From the Democratic Convention” by L. Brent Bozell and Willmoore Kendall.

1956-09-01: “The Campaign” by Sam M. Jones.

1956-09-15: “The Man Next to You” by John Chamberlain.

1956-09-29: “Reflections on a Right-Wing Protest” by Revilo P. Oliver.

1956-11-24: “The Liberal Line” by Willmoore Kendall.

1956-12-08: “National Trends” by L. Brent Bozell.

1957-07-13: “Integration Is Communization” by Richard M. Weaver.

1957-07-27: “Voice of the South” Sam M. Jones interviews Senator Richard Russell.

1957-08-03: “Utopia and Civil Rights” editorial.

1957-08-24: Buckley’s infamous editorial, “Why the South Must Prevail”.

1957-09-07: “The Open Question, Mr. Bozell Dissents from the Views Expressed in the Editorial, ‘Why the South Must Prevail’” by L. Brent Bozell.

1957-09-21: “The Court Views Its Handiwork” editorial.

1957-09-21: “Governor Faubus Clouds the Issue” by L. Brent Bozell.

1957-09-21: “The South’s ‘Granitic Opposition’” by James Jackson Kilpatrick.

1957-09-28: “No Trips to Newport” editorial.

1957-09-28: “Right and Power in Arkansas” by James Jackson Kilpatrick.

1957-10-26: “Britain Looks at Little Rock” by Anthony Lejeune.

The Issue

“Our Contributors—in this special issue on the South: Anthony Harrigan (“The South Is Different”) is an editorial writer on the Charleston (S.C.) News and Courier and a contributor to various magazines. James Jackson Kilpatrick (“But It Won’t Stay Buried”), author of The Sovereign States, succeeded the late Douglas Southall Freeman as editor of the Richmond News Leader, on which Richard Whalen (“Rural Virginia: A Microcosm”) is his editorial assistant. Andrew Lytle (“The Quality of the South”) teaches at the University of Florida. He was one of the contributors to I’ll Take My Stand, and has published four novels of which the latest is The Velvet Horn.”

The South Is Different: Anthony Harrigan

The South, Harrigan says, is still itself—not innocent, not unchanged, but whole in a way the rest of the country has forgotten. Though the highways came and the banks got taller, it didn’t sign on to the national conformity plan. It welcomes visitors, remembers its stories, holds fast to its customs. The court ruling of 1954 only deepened this resolve, uniting diverse communities through shared trial. He objects to being remade by advertising or national opinion. He says history isn’t just economics and politics. It’s Providence and people. People, remembering. This essay made it into the Congressional Record.2

Factories have been mechanized but not the people.

Rural Virginia: A Microcosm: Richard Whalen

Whalen’s Virginia moves slow, and on purpose. It’s a place modern on the surface but ancient in its reflexes. He’s skeptical of Northern idealists who talk integration while living segregated lives. He says the South won’t change at gunpoint. If anything’s going to shift, it’ll be through jobs, migration, and the quiet, patient erosion of time.3

Unlike fluid, incohesive city life, rural life is closely-knit and follows rigid, time-honored forms. The coming and passing of the seasons imposes an inflexible order on the lives of those who till the soil. Change is suspect.

But It Won’t Stay Buried: James Jackson Kilpatrick

In “But It Won’t Stay Buried”, Kilpatrick counters Harry Ashmore’s obituary for the Old South, arguing that Southern identity remains stubbornly alive. He met Ashmore back in ’54, when the South was still reeling from the Court’s ruling but hadn’t yet hardened. Since then, the region has been pried open by strangers, “doctors of sociology,” and the New York Times to be examined and diagnosed.

Kilpatrick isn’t swayed. Yes, there’s change—factories, cities, the usual—but Ashmore’s mistake is thinking you can kill a culture by reporting on it. Far from fading, Kilpatrick argues, outside pressure has revived Southern distinctiveness, binding the region closer in defiance of its eulogists. Some things, once rooted, are not so easily pulled up.4

The Quality of the South: Andrew Nelson Lytle

The Southerner is the classicist who enjoys the way, leaving the end to God.

Lytle reviews The Lasting South, focusing on the tension between two incompatible ways of thinking: Southern conservatism and the statist, secular impulses of liberal democracy. He frames the Southern mind as Apollonian, rooted in Christian tradition, reverent of limits, and wary of utopian abstractions, contrasted with the Faustian liberalism that promises power, equality, and immortality, but severs liberty from its theological roots. Lytle praises essays by Kilpatrick, Clifford Dowdey, and Richard Weaver, while criticizing others. Ultimately, he argues that as the South confronts liberal encroachment, its survival may depend on artists and writers to preserve its language, memory, and moral vision.5

The family and its connections are the basis of Southern society. If this goes, the South will go.

Sources & Bibliography

Bogus, Carl T.. Buckley: William F. Buckley Jr. and the Rise of American Conservatism. Bloomsbury USA, 2011.

Buccola, Nicholas. The Fire Is Upon Us: James Baldwin, William F. Buckley Jr., and the Debate Over Race in America. Princeton University Press, 2019.

Buchanan, Patrick Joseph. Conservative Votes, Liberal Victories: Why the Right Has Failed. Quadrangle/New York Times Book Company, 1975.

Burner, David., West, Thomas Reed. Column Right: Conservative Journalists in the Service of Nationalism. New York University Press, 1988.

Continetti, Matthew. The Right: The Hundred-year War for American Conservatism. Basic Books, 2022.

Crawford, Alan. Thunder on the Right: The "New Right" and the Politics of Resentment. Pantheon Books, 1980.

Edwards, Lee. Educating for Liberty: The First Half-Century of the Intercollegiate Studies Institute. Regnery Publishing, 2003.

Felzenberg, Alvin S.. A Man and His Presidents: The Political Odyssey of William F. Buckley Jr. Yale University Press, 2017.

Gottfried, Paul. “Rethinking William F. Buckley’s Quest for Respectability” in The Great Purge: The Deformation of the Conservative Movement. Washington Summit Publishers, 2015.

Gottfried, Paul., Fleming, Thomas. The Conservative Movement. Twayne Publishers, 1993.

Hart, Jeffrey Peter. The Making of the American Conservative Mind: National Review and Its Times. ISI Books, 2005.

Hemmer, Nicole. Messengers of the Right: Conservative Media and the Transformation of American Politics. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

Hustwit, William P.. James J. Kilpatrick: Salesman for Segregation. University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

Jewell, Katherine Rye. Dollars for Dixie: Business and the Transformation of Conservatism in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Kelly, Daniel. Living on Fire: The Life of L. Brent Bozell Jr. ISI Books, 2014.

Kilpatrick, James Jackson. The Southern Case For School Segregation. Crowell-Collier Press, 1962.

Lowndes, Joseph E.. From the New Deal to the New Right: Race and the Southern Origins of Modern Conservatism. Yale University Press, 2008.

Mattson, Kevin. Rebels All!: A Short History of the Conservative Mind in Postwar America. Rutgers University Press, 2008.

Mergel, Sarah Katherine. Conservative Intellectuals and Richard Nixon: Rethinking the Rise of the Right. Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Nash, George H.. The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945. Skyhorse Publishing, 1996.

Perlstein, Rick. Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus. Hill and Wang, 2001.

Reichley, James. Conservatives in an Age of Change: The Nixon and Ford Administrations. Brookings Institution, 1981.

Schneider, Gregory L.. The Conservative Century: From Reaction to Revolution. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2009.

Schryer, Stephen. National Review's Literary Network: Conservative Circuits. Oxford University Press, 2024.

Skinner, Kiron K.. The Strategy of Campaigning: Lessons from Ronald Reagan and Boris Yeltsin. University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Smant, Kevin J.. Principles and Heresies: Frank S. Meyer and the Shaping of the American Conservative Movement. ISI Books, 2002.

Stone, Roger., Colapietro, Mike. Tricky Dick: The Rise and Fall and Rise of Richard M. Nixon. Skyhorse, 2017.

Voegeli, William. “Civil Rights and the Conservative Movement.” Claremont Review of Books 8.3, 2008.

Harrigan (1925-2010) wrote for Southern Partisan, Chronicles, American Mercury, The Freeman, Shenandoah, Modern Age, The American Historical Review, Public Affairs, The Contemporary Review, Catholic World, American Heritage, and others. At one time he was assistant editor at the University of Florida Press. Some of his deepcuts:

Piazza Tales: A Charleston Memory by Rose Pringle Ravenel edited by Anthony Harrigan.

The Editor And The Republic: Papers And Addresses of William Watts Ball edited by Anthony Harrigan.

His Philadelphia Society speeches.

Richard J. Whalen (1935–2023), a New York native and Queens College graduate, began his journalism career at the Richmond News Leader under James Jackson Kilpatrick. He went on to write for Time, The Wall Street Journal, and later joined Fortune as a senior writer and board editor. His biography The Founding Father: The Story of Joseph P. Kennedy is a foundational text in Kennedy scholarship. He also wrote “on New York’s endangered architectural heritage” in A City Destroying Itself: An Angry View of New York. His book Catch the Falling Flag chronicled his brief tenure, and swift disillusionment, with Nixon’s 1968 campaign as one of Nixon’s aides/speechwriters along with Pat Buchanan. In 1975, he published Taking Sides: A Personal View of America from Kennedy to Nixon to Kennedy, a collection of political essays. (Full Bio) (Review of the News 1980 interview) (The New Leader 1959-09-28 Richard Whalen, “Labor Struggles in the South”)

Kilpatrick is better known than Harrigan and Whalen, but here’s a few links:

Internet Archive search results,

Some of his editorials.

His Philadelphia Society talks.

His papers at UVA.

A thesis on his changing views.

If you read this Substack, Lytle needs no introduction, but just in case. And here.

The 50s through the 80s was an interesting time for Conservatism. Buckley had a dominant role. It was a sort of cosmopolitan conservatism. Not at all like what I would call small-town, local community conservatism. It mirrored the change in how capitalism was understood as well. Corporate capitalism became the default as local, mom-and-pop family store capitalism became subject to what we now see as neo-conservatism, or as I call it, "state-sponsored capitalism." What is often missed in discussions about these trends and ideologies is that the old conservatism prior to Buckley was more agrarian and of the land than cosmopolitan and urban. The cultural conservatism that I've witnessed throughout my college years seemed to be trapped between its old agrarian roots and the need to compete for readers of magazines. As we are in the midst of another major shift, it will be interesting to see what will emerge from the old agrarian, local community conservatism that has a more historic and universal appeal.

Thank you for reading, Mr. Brenegar, and for your thoughtful comment, they always challenge me to think more deeply.