M.E. Bradford's Last* Essay

A Neglected Classic: Filmer's Patriarcha

The following essay is from Saints, Sovereigns, and Scholars: Studies in Honor of Frederick D. Wilhelmsen edited by R.A. Herrera, James Lehrberger, O. Cist., and M.E. Bradford. Published by Peter Lang, 1993.

At the book’s beginning the editors honor Bradford:

M. E. Bradford (1934-1993)

As this volume was in the final stages of preparation, editor and contributor M. E. Bradford died following heart surgery on March 3, 1993. The author of eight books and more than three hundred articles, Professor Bradford was a scholar dedicated to the preservation of Christian Civilization. For more than a quarter of a century, he was a close friend and colleague of Frederick D. Wilhelmsen at the University of Dallas. When he was asked to help edit this festschrift, he gladly and generously agreed to do so; in more than one way he was indispensable to this project. Ten days before his death, Doctor Bradford reviewed and approved the proof pages of his own contribution to this volume. We are honored to publish *one of the last articles that this admirable scholar completed.

“A Neglected Classic: Filmer’s Patriarcha”

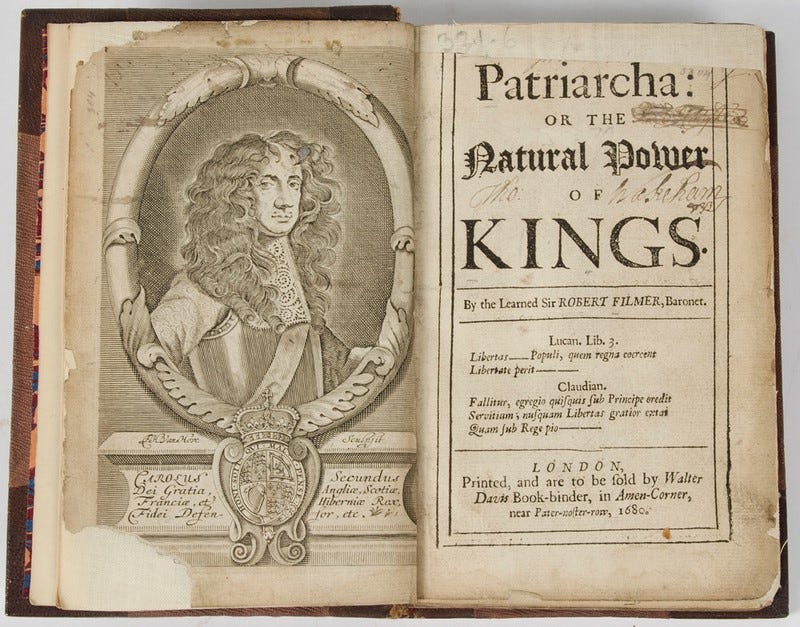

In a world gone mad in its “official” devotion to the aboriginal rights of man we have perhaps reached the proper moment for reconsideration of the antithetical political position, the doctrine of Sir Robert Filmer (1588-1653) as developed in his extraordinary, posthumously published treatise, Patriarcha. Filmer’s teaching is, as stated briefly, that the authority of the state is rooted in the natural authority of fathers—or, more usually, of grandfathers. And of elder brothers over their younger siblings, grandmothers over younger women in their family, etc. Filmer, the quiet magistrate and knight of Kent, writes as a legitimist, a high Tory, and a man of great learning. In reflecting on government he teaches nothing about social compacts, real or implicit, except to argue that many of them are fictional. His understanding of how political authority came into being reaches back to when Adam first maintained his establishment in Eden and when Noah sailed about the Mediterranean distributing some of his property among his sons.1 The ground for what Adam and Noah prescribe in fulfillment of their patriarchal duties is in the Order of Being itself, is ontological, and not in their agreements concerning policy with those in their keeping.

For once Eve was created and social order began, there had to be authority that went with responsibility, since God, Filmer insists, has made us all (and most especially fathers) accountable, but not free. Filmer’s concern in these speculations is to confront arguments asserting primordial human equality—or something close to it: arguments which therefore conflict with Filmer’s assumption that all authority begins in the tie of blood. Filmer’s critique of such doctrine is radical, with (and against) those who proceed from the idea of some state of nature where individuals exist solus, and from which their rights as individuals derive. There are other English royalist thinkers who reason from history, philosophy, or law. However, though the ultimate defender of the prerogatives of his prince, King Charles I, Filmer pleads his case as do many of his seventeenth-century Puritan adversaries—from Scripture, and only incidentally from other authorities. And he argues without any legalist compromises moderating his royalism—with such rigor that he has become in reputation almost a caricature of his own political opinions. Yet Patriarcha is almost never given a careful reading. All of which is to say that most strong views concerning Filmer come from writers who know nothing about his work and issue instead from ideologically motivated posturing. They are ignorant instances of the argument ad populum. As regards his central proposition, I wish (in brief) to correct the situation which I describe, to recover, in a personal observation, the hyperbole of Filmer as a correction for the even larger hyperbole of John Locke and his followers.

Patriarcha was written in the 1630’s—probably between 1634 and 1638. But it was not published until 1679, when Charles II prorogued Parliament in order to prevent the adoption of an Exclusion Bill—a direct attack on the principle of legitimacy, which is at the heart of Patriarcha. Since that time the book has enjoyed another sixty-five years of significance as an influence in partisan political debate and then two hundred forty-nine years as a chapter in the history of political theory. But it really ceased to signify in a polemic fashion after the Glorious Revolution. Since 1688 it has been, except as regards succession, a counter in largely symbolic exchanges. And because Filmer’s discourse is, as I said earlier, so full of hyperbole, such symbolic exchanges have been numerous. A new edition by the Cambridge University Press should do much to increase attention to what Sir Robert actually wrote.2

The lasting significance of Filmer’s teaching has to do with which metaphors Western civilization prefers in understanding the origins of human society. The point is that in an egalitarian culture which has been that way for more than one hundred years, the obvious superiority of Filmer’s metaphor for social beginnings to the widely accepted preference for tropes given summary expression by John Locke is difficult to recognize as what it clearly is: difficult unless it is advanced with great care, appealing to family feeling without threatening individual vanity. Filmer’s metaphor is that society is, at bottom, like a family and that basic authority and obligation in the original social order were providential—a fact, not something to be voted in or out. As we all know, Locke’s preference was for a state of nature, of the savage isolate who, in a kind of dangerous Eden, finds the source of his political rights.3 The difficulty with Locke’s choice of defining image is that, first of all, it does not include any provision for children. It postulates a race of men who are all adults. In assuming human equality the Lockean myth is subject to the criticism of the American Declaration of Independence advanced by John C. Calhoun. In his June 27, 1848 speech “On the Oregon Bill,” Calhoun examined the proposition that “all men are born free and equal” and observed with impatience,

Taking the proposition literally (it is in that sense it is understood), there is not a word of truth in it. It begins with “all men are born,” which is utterly untrue. Men are not born. Infants are born. They grow to be men. And concludes with asserting that they are born “free and equal,” which is no less false. They are not born free. While infants, they are incapable of freedom, being destitute alike of the capacity of thinking and acting, without which there can be no freedom. Besides, they are necessarily born subject to their parents, and remain so among all people, savage and civilized, until the development of their intellect and physical capacity enables them to take care of themselves. They grow to all the freedom, of which the condition in which they were born permits, by growing to be men. Nor is it less false that they are born “equal.” They are not so in any sense in which it can be regarded; and thus, as I have asserted, there is not a word of truth in the whole proposition, as expressed and generally understood.4

Ignoring the logic which Calhoun understood so well, Locke insisted that children contract with their parents, that society is “created by thinking and willing.”5 According to the great Whig, the world before history was made up of “... people that were naturally free, and by their own consent either submitted to the Government of their Father or united together, out of different families, to make a government.”6 Which is a dreadful fiction, on a par with his insistence that, however in peril of death, harm, or subjection, any order of men or any person, unrestrained for the moment and secure from compulsion, is free and equal to anyone else similarly situated.

The difficulty in Locke’s theory is that if children operated as free agents in such a “state of nature,” the human race would swiftly be extinguished. For they cannot function successfully as free agents for at least fifteen years—to take an optimistic view. Nor indeed can most adults, without the supporting network of family, friends, associates, brethren, and countrymen. But there never was such a place or time as Locke’s “state of nature.” It is pure fiction, an ideological construct, a piece of pleading designed to function in a polemical response to another, very different, political statement: in Locke’s own phrase, as included in the title of his Two Treatises, it is part of an effort to confound “the false principles and foundation of Sir Robert Filmer” so that they “are detected and overthrown.”7

As Peter Laslett writes, Locke “did not succeed in establishing against Filmer that consent pervaded all social relationships. He did not appear to realize that this would have to be done if naturalism [i.e., the theory that the beginnings of government are providential] is to be refuted. He explained family relationships by saying that they were based on contract and not on status ....”8 All of which is a contemptible fiction, and as political philosophy, decidedly inferior to the notion that the family is the original and the raw material out of which any ancient social order was assembled. The sequence in forming a society is as follows: first the ontological connection, in blood relations; then additions of members of families into which one of your own family has married; then a gathering in of those who are linked to you by common causes and common enemies, covering both intense bondings, as in war, and milder forms of association, as in occupation or business; finally, enlargements by common beliefs, as in political cooperation and common religion. Units developed by these stages, if they have a common language as additional adhesive, are the building blocks of nations, political entities that think of their leader as a “father,” whether he be a king, a chief magistrate, or a priest, none of whom believe that they are free, or that anyone is equal to anyone else. Out of this sedimentary process come custom, law, and even constitution: out of “this lordship which Adam by creation had over the whole world, and by right descending from him [to] the Patriarchs ....”9

Of course, Filmer’s biblical arguments, when they go beyond how best to determine the status of legitimate princes, tribal chieftains, or fathers—and beyond how such distinctions invite a certain reverence for the mysterious origins of society—are not entirely persuasive. All who are in such authority hold their offices “by the ordinance of God himself.”10 God, by making them the sons of their fathers, gave each of these their station, which is part of what they are: gave them “the power of government [which] did originally arise from the right of fatherhood.”11 This observation, however, says nothing about their powers, which are determined by particular histories. As I have argued elsewhere, man is designed to live under a “social and political order,” under an authority that is restrained by some kind of inherited politics.12 And therefore there are limitations on any ruler or prince, even the Great Turk or the Khan of China. For these reasons, I am still a Whig and cannot give my assent to Filmer when he says that the Great Charter is not binding and that whatever the Parliament does is by the king’s sufferance.13

That kings, chieftains, and patriarchs are much inclined to be tyrants and to sin against God if their authority is absolute is a matter of historical record; so is the fact that subjects of even the best of princes are often disobedient—determined to choose their own way. Yet individuals have a primordial reality unto themselves, along with their roles in society. They are not a fiction. Human beings are born and die one by one. Moreover, religion teaches us that we are judged, from everlasting unto everlasting, with respect to our own spiritual condition and our merits; and there is not enough of this truth in the Patriarcha—apart from Filmer’s teaching about personal complicity in rebellion.

Nevertheless, even though many men (and certain orders of men) unknowingly occupy, in the human family, a position something like that of children, even though God is Our Father in Heaven and all lesser authorities from Pope to Chief Magistrate to Commander in Chief and County Judge are all to this day in loco parentis without benefit of recognition, in a world where the aforementioned bond between “parents” and “children” is deteriorating and rebellion in the ontological, Promethean sense is commonplace, it is still possible that some of Filmer’s truth will survive in all of the little “social units” which persist “out there,” looking inward, remembering their own history, trying to avoid becoming merely parts of government. For the way in which moderns tend to “miss something” in the impersonal operations of state-sponsored beneficence, the way that they do not find there the link between the generations and the human solidarity with those who issue from us or who gave us life speaks of something familial which our nature requires—or from the closest things to such kindred as we may find.14 Even though inequality is ineradicable, in the social state affection shores up responsibility and guarantees the parental grant of liberty as no treatise, oath, or compact ever will.

To our sense of security in such parenting we respond in yearning as, on our own as adults, we remember, even long after our parents are dead, the most secure state (however imperfect) we ever knew. Though the American government rests on contract, society (which is logically prior to the state) does not. For children are born into society, not into a polity or state. Families are the component parts of society and the guarantee of its continuity. Families contain little brothers and older brothers, orphaned nieces and the elderly uncles of your deceased father-in-law. In order to watch over all of these (and the dignity of the family in general), the patriarch must have authority. Also he must be able to keep some of the “family property” together, though not primarily for his own use. And he cannot treat all of his charges in the same way, even though their “childlike” dependent status will not go away with the mere passage of time, as do the limitations of children.

With regard to his fabulous pre-social state, Locke asks:

If Man in the State of Nature be so free as has been said; if he be absolute Lord of his own Person and Possessions, equal to the greatest and subject to no Body, why will he part with his Freedom? Why will he give up this Empire and subject himself to the Dominion and Controul of any other Power? To which tis obvious to Answer, that though in the state of nature he hath such a right, yet the Enjoyment of it is very uncertain ... full of fears and continued dangers [even though every man is king].15

All of which is directly to Filmer’s point. Most of us will, as human beings, see that Locke’s description of social arrangements, even after contract has replaced a state of nature, is a cold one and that Filmer’s affectionate patriarchy is sometimes, when we have put our foot wrong, a better help to us than a fierce advocacy of all our own “rights.”16 And, if Filmer is correct, nothing compels us to adopt Locke’s contract. Fatherly power is loving and indulgent, since a father sees his own honor in the lives of his children—and, I might add, sees his own problems in theirs. It is no accident that we prefer to invoke God as Father than as just judge. To say that the Czar is never really the “little Father,” Pater Patriae, is like saying that no judge is ever disinterested and no grade given on a term paper ever fair or accurate. It does not affect the paradigm of how these roles are supposed to operate, or our sense of their relative legitimacy. For we are free (and safe) only by way of our relation to someone else. Nor is there any liberty without context, except for the kind of liberty that frightens Mr. Locke. And that liberty in context is our point of departure as we begin to contract on our own.

Filmer, of course, did not suggest (as Locke pretends) that all princes and chieftains are the products of uninterrupted succession. The authority of Adam was for him the type of all fatherly authority, exemplary and politically instructive, even though “true fatherhood itself was extinct” and only approximations could occur.17 Yet he reasoned that this concession in no way affected the validity of his argument, so long as there were fathers and sons to renew the process he describes. Such observations indicate the sophistication of his thought, which his enemies almost never acknowledge. But a good many of them have always taken Sir Robert seriously, even when like Locke, the Whig historian James Tyrell, and the theorist Algernon Sidney, they distorted his position. These, along with a few admirers, have kept his reputation alive. The Virginia Tory parson Jonathan Boucher wrote fine sermons out of the Patriarcha. Early in this century, Professor J. W. Allen wrote that “as a political thinker he [Filmer] was far more profound and far more original than was Locke.”18 And Peter Laslett, working outward from the implications of Filmer, composed his extraordinary study of a bygone familial England in The World We Have Lost.19

I will quote once more from Laslett in concluding these remarks on Filmer. In his introduction to Patriarcha he observes that Filmer did not think of society as “created by conscious thinking” or as “kept working by conscious thought.” Then Laslett concludes that “society for him was physically natural to man. It had not grown up out of men’s conscious thinking, it could not be altered by further thinking, it was simply a part of human nature.”20 And he suggests that, on reflection, most of us are bound to agree with Sir Robert Filmer on this point. That is, unless like the young man who betrays the head of his family in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s fine story “My Kinsman, Major Molineux,” we have listened to the original of all revolutionaries and been caught up in the fancy of living absolutely on our own. But that dream rarely lasts very long in the clear light of day, at least not once we learn about the other side of independence qua isolation—the difference between strangers and blood relations.

M. E. Bradford

University of Dallas

Irving, Texas

Sir Robert Filmer, Patriarcha and Other Political Works, ed. with an Introduction and Notes by Peter Laslett (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1949), p. 59.

Sir Robert Filmer, Patriarcha and Other Writings, ed. with an Introduction by Johann P. Sommerville (Cambridge, 1991). This work contains a useful Filmer bibliography.

John Locke, Two Treatises of Government: A Critical Edition, Introduction and Apparatus Criticus by Peter Laslett (Cambridge, 1964).

John C. Calhoun, Calhoun: Basic Documents, ed. John M. Anderson (State College, PA: Bald Eagle Press, 1952), p. 291.

Locke, p. 555.

Ibid., p. 361.

Ibid., p. 153. Locke’s entire First Treatise is a response to Filmer.

Laslett’s Patriarcha, p. 40.

Ibid., p. 59.

Ibid., p. 57.

Ibid., p. 79.

M. E. Bradford, Remembering Who We Are: Observations of a Southern Conservative (Athens, GA: Univ. of Georgia Press, 1985), pp. 16-17.

Laslett’s Patriarcha, pp. 117 and 119-120.

Ibid., p. 40.

Locke, p. 368. My language in brackets.

Laslett’s Patriarcha, p. 61.

Ibid.

J. W. Allen, “Sir Robert Filmer,” The Social and Political Ideas of some English Thinkers of the Augustan Age, A.D. 1650-1750, ed. F.J.C. Hearnshaw (London, 1928), pp. 27-46. The best of recent commentary is in James Daly’s Sir Rohen Filmer and English Political Thought (Toronto: Toronto Univ. Press, 1979). Also of value is Gordon J. Schochet’s Patriarchalism and Political Thought (Oxford, 1975).

Peter Laslett, The World We Have Lost (New York: MacMillan, 1984).

Laslett’s Patriarcha, p. 42.