From the Archives: A 1983 Interview with Andrew Lytle

I’m currently working on an essay for an actual magazine and happened upon the March 1984 issue of Nashville! magazine. Inside was an interview with Andrew Lytle and an article on the Fugitive Poets and Southern Agrarians. Thought y’all would appreciate it.

An Interview with Andrew Lytle

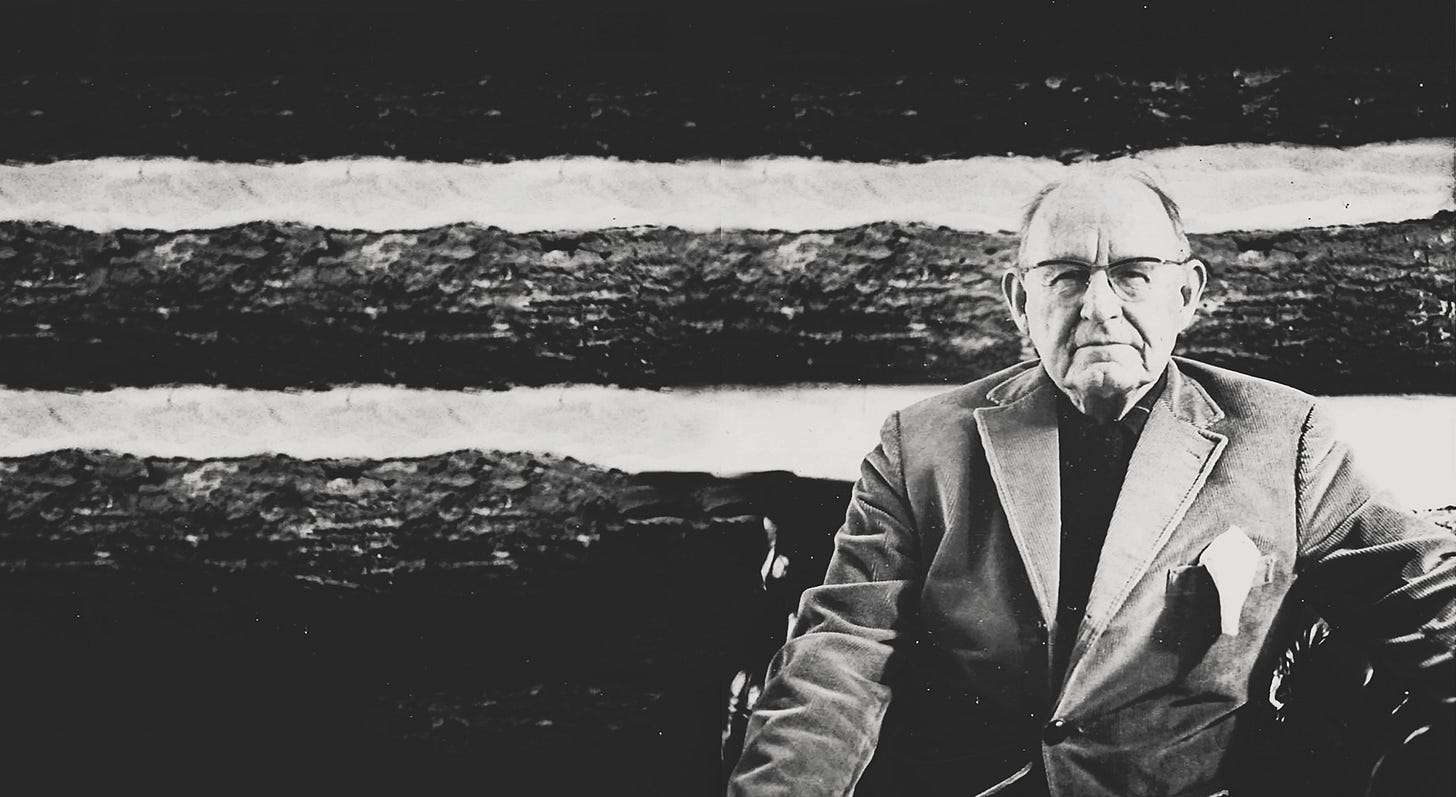

One of the most adamant essays in I'll Take My Stand is “The Hind Tit” written by Andrew Nelson Lytle. Born in Murfreesboro in 1902, Lytle was educated at Vanderbilt, Yale, Oxford and the Sorbonne. Today, at 82, Lytle lives on Monteagle Mountain in a log cabin that belonged to his mother.

An author, historian and professor for more than 50 years, Andrew Lytle has eloquently defended the rich and gracious morality that he considers uniquely and innately Southern. He has been called one of the South's finest contemporary novelists. Presently, his work is receiving long-deserved attention. His 1957 novel, The Velvet Horn, has been reissued. An anthology is planned, and other Lytle publications are soon to be reissued.

The air is clear and very cold on top of Monteagle Mountain. Mr. Lytle opens the door of his cabin. There are family portraits on the walls, Persian rugs on the hardwood floors and antiques everywhere. “Sit by the fire and warm yourself, daughter,” he says, indicating a rocker in front of the stone hearth. His mind is very clear, his memory excellent. He spills over with history and with his message.

Nashville: Why did the Agrarian movement happen at Vanderbilt? Why not some other place?

Lytle: Only God can answer that question. Nashville was the center of a homogeneous society. Most of the writers came from Tennessee and Kentucky, nearby. They had a common inheritance, but they were all there by accident. What brought them all together was this. The South had been defeated during the War of Northern Invasion, but after the first World War we were disconcerted to find that things were not equal yet. There was the same old antipathy. The South was still a conquered province. It was a common feeling among us that industrial might would obliterate the family and society. We were protesting, our backs to the wall. We had no sense of being prophets. But the depression set in and made us look like prophets.

Nashville: What is your impression of the reaction to I'll Take my Stand?

Lytle: There were two reactions to what we said. Southern liberals criticized us, and others were sympathetic but didn’t believe it would happen. And what was happening was not only wrong, it was dangerous, it could destroy a way of life. Now we have the complete triumph of the industrial revolution, but our critics couldn’t understand that the dominant way of life could disappear. Those who called us romantics were wrong. We were advocating something real. Agrarianism isn’t a myth. Land is not a myth. Corn is not a myth. We took the word Agrarian because the best societies were based on close association with the land. The family and the family-size farm and business were the basic unit of society. By destroying the family, you make the individual dependent on some abstract entity — like a federal government agency. What we have is the abstract superimposition of the financial corporate state on a system based on real property.

Nashville: About land and corn — you once tried to become an Agrarian, a farmer. What happened to you, and what about groups who try to return to the land today like the Farm in Summertown?

Lytle: I bought a little “throw-away” farm, but there wasn’t any point. It was impossible to be independent. I couldn’t afford machinery to really farm. You had none of the usual habits of the farm and the town I grew up in. There was no system of support, no country community. In the 1940s I might have taken eggs to town to sell. You can’t take anything to town now and get cash for it.

As for the Farm, you can’t dope and farm, too. They are making an effort to recall what has been lost. But they formed a kind of cult. You can’t do that. They are, at least, dealing with nature.1

Land is a living thing. It takes a fine religious belief in what you’re doing. Industrialism uses nature, exploits it and destroys it. Agrarianism is a Christian and European attitude toward the land. From the land comes bread and meat and independence — and democracy. You'll be careful who you vote for for governor because you have something real to lose.

What the Agrarians were trying to do was to reuse, restore somewhat, our European inheritance which was a Christian inheritance. The South was in a formless way still religious.

Nashville: What do you mean by Christian and European?

Lytle: God was sovereign. The land was His and everything in it. The king was His secular overseer and the bishop His religious. The moment that God ceased to be sovereign, history took the place of God. History is man judging man, not God judging man. Everything becomes relative, and chaos is the result.

In the European Agrarian society and later here in the South there was family, connections, order. Today there is no division between what's public and what's private. To confuse the two is the basis of tyranny. It violates the individual’s integrity.

Nashville: If industrialism has triumphed, then what hope do Southerners have of building lives of quality?

Lytle: What is divine in man is his sense of craftsmanship. If catastrophe happens, you may survive if you are an artist, if you can create a thing of utility or beauty. The economic basis of Christendom was craftsmanship. You must either make or do. That’s your only defense against an impersonal, industrial state.

The Company Was Olympian: Fugitives and Agrarians by Amy Lynch

During the early 1920s, the Fugitive poets called Nashville home, and later that same decade the city saw the publication of the controversial Agrarian manifesto, I’ll Take My Stand. This flurry of literary activity, often called the Southern Renaissance, had its beginnings in 1914 when John Crowe Ransom came to Vanderbilt to teach English.

Born in Pulaski, Ransom was a Rhodes Scholar and an Oxford-trained classicist philosopher. He soon encountered a promising student, Donald Davidson, from Campbellsville, Tennessee. They became friends. During the summer of 1915, Davidson and fellow student Stanley Johnson began visiting coed Goldie Hirsch at her home near Vanderbilt. There the students met Goldie’s half brother, Sid Hirsch, and found themselves fascinated by his far-flung and intriguing ideas. Hirsch was challenging, domineering and, the students decided, blatantly wrong about some things. Davidson and Johnson decided that the person to disabuse Hirsch of some of his fantastic misconceptions was Ransom, their English instructor. Ransom met Hirsch, and found him stimulating. The four began meeting regularly to discuss the classics, faraway places, art, and the abstract.

Sidney Mttron Hirsch, (1885-1962) the center of and catalyst for the discussions, was no ordinary Nashvillian. He ran away from home to join the Navy at an early age and for several years traveled throughout Asia and Europe. Fascinated by the mystical and remote, Hirsch read widely but without traditional guidance or education. He formulated some fantastic notions about the world. He also grew into an exceptionally handsome man. The heavyweight boxing champion of his navy fleet, Hirsch modeled for Rodin. He cultivated friendships with literary greats like Gertrude Stein and Edwin Arlington Robinson, and finally he tried writing too. A play entitled The Fire Regained was the robust result. It was perhaps the most outlandish theatrical performance in Nashville history.

The 1913 extravaganza featured classical characters and was performed in front of the newly-completed Parthenon. The cast numbered 600. A full-page advertisement in the papers invited visitors to see “The Flight of a Thousand Doves, The Revel of Wood Nymphs, the Thrilling Chariot Race, the Raising of the Shepherd from the Dead, and the Orgy of the Flaming Torches.” Railroads reduced their fares for out-of-town visitors, and trolley companies ran special cars to accommodate the 5,000 people who turned out for six performances between May 5 and May 8.

Those performances were nearly incomprehensible, but The Fire Regained was a smashing success. On the second day, one of the chariots rolled over in a cloud of dust — raised, perhaps, by the 300 sheep in the cast. The thousand doves in their flight implicate one of the temple virgins who is sentenced to be burned for her impurity. Happily, she is rescued by Hermes and turns out to be Athena herself. A happy ending, even if audiences couldn’t make heads or tails of it.

After The Fire Regained Hirsch remained in Nashville, restless and intense, but writing nothing of literary note. His one play remained his only achievement as a writer, but his influence on American letters was just beginning. Throughout 1915 other students joined the meetings: William Yandell Elliot from Murfreesboro, William Frierson and Alec Stevenson.2

Evidently the meetings were fun. During 1915 Stevenson called them “a gorgeous time.” He wrote to a friend, “Nat Hirsch, Stanley Johnson, Donald Davidson, John Ransom, and Sidney Hirsch were the company last night and it was Olympian.”

The weekly meetings continued the following fall, but behind the scenes something happened that would eventually change the group forever. At 28, John Crowe Ransom began to write poetry. The story goes that one afternoon he asked Donald Davidson to go for a walk on campus, and he showed his first poem to his young friend. Shortly afterward, World War I broke up the group temporarily. Several Fugitives fought overseas, and some stayed in Europe to study after the war was over. But the core group returned to Vanderbilt in the early 1920s. They began to meet again in the home of Hirsch’s brother-in-law, James Marshal Frank, where Hirsch was living. Today the Frank home at 3802 Whitland Avenue is marked by a state historical marker. The discussions resumed with 11 or 12 regulars. Allen Tate from Kentucky joined the group.

In the fall of 1921, Ransom showed one of his poems to the group and found they made good critics. That evening proved so exciting that other members began bringing their verse. Talk turned from philosophy to poetry, and throughout the winter of 1921-22 the poems piled higher. In March someone suggested that they publish their work, and the proposed magazine was named The Fugitive. The magazine’s title was a reference to Hirsch’s conception of the archetypal fugitive in poetry — an outcast, a wanderer often with mysterious knowledge. The first issue made clear, however, that this Fugitive was fleeing the “high-caste Brahmins of the Old South.” Proclaiming that traditional Southern Literature had “expired,” the Fugitives strove to produce a new style of poetry. They had little use for moonlight and roses.

The first issue of The Fugitive must have been fun to produce. It contains poems under pseudonyms like Robin Gallivant, Roger Prim, L. Oafer, and Henry Feathertop. The 500 copies sold well in Nashville, and the rest were sent to editors across the country. Reviews were mixed at best. Only three copies were sold in New York. Merrill Moore joined the group soon after the appearance of the first issue, and Robert Penn Warren and Jesse Wills joined during the next year. The members became more seriously committed to poetry.

The Fugitive was published until 1925. By that time, members had developed other interests which took priority. From then until 1928 the group slowly drifted apart. 1928 marked the publication of an anthology and the formal end of Fugitive poetry.

Agrarians. In 1925, when the last Fugitive was issued, the Scopes Trial in Dayton, Tennessee, caused a national sensation. During the hot circus-like summer, Northern reporters interviewed rabid fundamentalists, local “characters,” and tobacco-chewing moonshiners squatting in the shade in front of the courthouse. Tennesseans were portrayed in the Northern Press as ignorant, obstinate and lazy. Nashvillians resented the picture painted by the press, and over the next five years the four primary members of the Fugitive group (Robert Penn Warren, Allen Tate, John Crowe Ransom and Donald Davidson) along with eight other Southerners developed a strong and complicated response.

That response was a symposium on Southern culture and history entitled I’ll Take My Stand, and they certainly did. The Agrarians, as the group came to be called, argued that Southern society fostered individual integrity, stability, character, and aesthetic qualities unavailable in the industrialized North. Southern society was still tied to the land, they argued, and therefore allowed for a happy integration of work and play as well as for order and quality. Advances in education, economy and the arts must not be made at the expense of Agrarian values. The North, they were convinced, had lost this precious heritage and had given way to impersonal and brutalizing industrialism. The South must not do the same.

I'll Take My Stand produced as heated a controversy as any Southern publication ever printed. The authors were deluged with editorials, newspaper articles and letters of protest from every part of the country. It was called the “most audacious book ever written by Southerners.” Critics called the authors dreamers trying to stop progress, Neo-Confederates, and romantics trying to escape the realities of modern life.

In spite of criticism, the Agrarians continued their scholarly defense of Southern Agrarian traditions and values. Some of them became very well-known. Allen Tate wrote to Donald Davidson in 1942 “Never fear: we shall be remembered when our snipers are forgotten.” So it would seem. I’ll Take My Stand remains a landmark in Southern literature, an articulate defense of the humane tradition, of beauty over progress, and of spiritual wealth over material profits.

A Fugitive and Agrarian Bibliography by Marice Wolfe

The Works:

The Fugitive. Nashville, 1922-1925. Nineteen issues. The little poetry magazine through which the Fugitives discovered themselves and were discovered.

I’ll Take My Stand: The South Brothers, 1930. Reprinted by Louisiana State University Press, 1977. The Agrarian manifesto — disparate views of a common cause.

Davidson, Donald, Southern Writers in the Modern World. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1958. An insider-historian’s view of the genesis of the Fugitives and the Agrarians.

Lytle, Andrew Nelson. A Wake For the Living. New York: Crown, 1975. His family as subject offers an invitation to explore the bases of Lytle’s fiction and his Agrarian beliefs.

Ransom, John Crowe. Poems and Essays. New York: Vintage Books, 1955. An opportunity to sample vintage Ransom in poetry and prose.

Tate, Allen. Collected Poems: 1919-1976. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1977.

Warren, Robert Penn. All the King’s Men. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1946. Robert Penn Warren Talking: Interviews 1950-1978. Floyd Watkins and John T. Hiers, eds. New York: Random House, 1980. The most various and durable of the productive Warren’s work in many genres and a chance to listen to the man.

The Studies:

A Band of Prophets: The Vanderbilt Agrarians After Fifty Years. William C. Havard and Walter Sullivan, eds. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1982.

Fugitives’ Reunion: Conversations at Vanderbilt May 3-5, 1956. Rob Roy Purdy, ed. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1959.

Cowan, Louise. The Fugitive Group: A Literary History. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959.

Rubin, Louis D., Jr. The Wary Fugitives. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978.

Stewart, John L. The Burden of Time. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965.

Young, Thomas Daniel. Waking Their Neighbors Up: The Nashville Agrarians Rediscovered. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1982.

The books listed above and a thousand more by or about the Fugitives and Agrarians can be found in the Jesse E. Wills Fugitive/Agrarian Collection housed in the Special Collections section of the Vanderbilt University Library. The collection also contains 75 shelf-feet of letters and manuscripts relating to the writers and poets. Especially valuable are the letters of Andrew Lytle and Donald Davidson. Splendid photographs of the Nashville-based writers line the walls. If you want to learn about the Fugitives and Agrarians, Special Collections is a delightful place to browse. The General Library Building is located at 219 21st Avenue, South. Hours for the Special Collections section are 8-5 Monday through Friday and 9-2 Saturday. Phone: 322-2807. (Marice Wolfe is Head of Special Collections at the Vanderbilt University Library.)

Related Essays:

The Summertown farm mentioned in relation to Lytle’s “dope and farm, cult” comment is some type of hippie commune that’s been around since the 1970s. The Wiki

I fixed a typo/error. William Frierson was missing but Elliot was mentioned twice. Also, the article leaves out Walter Clyde Curry.

Thank you for posting this. This time in history is difficult to see clearly. It helps to go back two hundred years before the Agrarians to the time of the European migration to the colonies. New England, as we still call it today, was an outpost of European aristocratic culture. The South was settled as a second migration from those who first migrated from Europe into the Northern colonies. My German and Scottish ancestors settled in the Piedmont region of North Carolina beginning in the early 1700s. Their presence can still be seen today. A third migration began when new generations of the original settlers moved West into the frontier. Industrialization in the South and West came later and continues today. A settler culture is tied to the land. The Agrarian idea was not an ideal. Not some mythic notion to inspire the spread of subsistence farming. For many people are tied to the land, it is all they have. In the late 19th century, just prior to the emergence of The Fugitive and the Agrarian perspective, Fredrick Jackson Turner declared that the frontier of the US was now settled. The frontier was closed. I believe that Lytle and his circle of scholars showed that the frontier ideal was not about settlement, but about a relationship to and with the land. The land still beckons young men and women to leave the confines of urban/suburban culture and venture out to claim their few acres of dirt. For this reason, the Southern culture they describe remains alive in fresh forms, even as industrialization ebbs and flows as an alternative culture.