Eggnog Nationalism

The Nog Wars: A Battle for Tradition

Winter often brought reprieve in the wars of the past, but not in the Eggnog War. Unlike the fashionable moral ambiguities peddled by our gender-ambiguous storytellers, this war permits no compromise. Here we find no fashionable shades of gray. We’re not flipping houses. The Eggnog Question divides as clearly as foundations, rock against sand. Eggnog-haters are going back!

The history proves as substantial as the drink itself. In Eggnog, we find something quintessentially American, a Christmas tradition that speaks most clearly in a Southern accent. What started in Albion’s taverns grew to something else. Something ours.

The Consensus

Posset is an old drink from an old world. Hot ale or wine and eggs and spices thrown together in medieval halls when common folk could only talk about its smell. By the 13th century, milk and sugar joined the mix, cementing its status as a drink for the lords and ladies.

The drink crossed the Atlantic with British settlers in the 1700s, and the new world changed it. Caribbean rum, cheap and easy to find, replaced the brandy and sherry of the old country. With an abundance of milk and eggs, it became a drink enjoyed by Yankees, Yeomen, Cavaliers, Crackers, and Fur Trappers. The name “Eggnog” emerged during this period, though its origin remains disputed. Some claim it came from sailors combining “egg” with their “grog.” Another group says it refers to the word “noggin” borrowed from Scottish drinkers who knew their small cups well. Others point to Norfolk’s strong ale called “nog.”

The word “Eggnog” first appeared in American records toward the end of the 18th century, finding its most thorough early description in William Attmore’s 1787 “Journal of a Tour to North Carolina.” He noted, with particular interest, that the taking of “drams” before breakfast was not merely accepted but customary in North Carolina. His Christmas Day account preserves the precise preparation: five eggs separated, yolks mixed with brown sugar, whites beaten until astonishingly firm, these elements combined, and rum carefully stirred into the mixture.

Prior to Attmore’s notes, Jonathan Boucher, a Maryland clergyman, philologist, and friend to George Washington, referenced “Eggnog” in a poem composed around 1775, yet published later. By 1788, the term began appearing in documents throughout the colonies, establishing its place in early American vernacular.

On the ſubſequent morning to that of his departure, he breakfaſted at a tavern, with fome American travellers, who fortified themſelves against the cold by a hearty draught of egg nog*, and by putting on their ordinary apparel, great coats and wrappers, trowſers and woollen focks, and mittens and filk handkerchiefs; Mr. Weld, and a young gentleman from the West Indies were highly diverted with this ludicrous mafquerade, at the fame time experiencing no particular annoyance from the ſeverity of the weather, though in their customary dreſs. (*Egg nog is a compoſition of new milk, rum, eggs, and fugar, beat up together. Index: Egg-nog, an American beverage.) Historical Account of the Most Celebrated Voyages, Travels, and Discoveries from The Time of Columbus to The Present Period by William Fordyce Mavor (1801)

Consensus Concerns

1. Definitions

Many rely on the Oxford English Dictionary’s outdated definition and etymology:

egg-nog(g: (ˈɛg-ˈnɒg) Also (rarely) egg-noggy. [f. egg + nog strong ale.] A drink in which the white and yolk of eggs are stirred up with hot beer, cider, wine, or spirits.

1825 Bro. Jonathan I. 256 The egg-nog‥had gone about rather freely. 1844 Mrs. Houston Yacht Voy. Texas II. 179 Followed by the production of a tumbler of egg-noggy. 1853 Kane Grinnell Exp. xlvi. (1856) 428 And made an egg-nogg of eider eggs. 1872 Cohen Dis. Throat 91, I would rely chiefly on egg-nog, beef essence, and quinine. (OED Second Edition. 1989)

eggnog (n.) /ˈɛɡˌnɔɡ/ (EG-nawg): A drink in which the white and yolk of eggs are stirred up with hot beer, cider, wine, or spirits. Also egg-nog, egg-nogg, (rarely) egg-noggy. Etymology: < egg n. + nog n. strong ale. The earliest known use of the noun eggnog is in the 1820s. OED's earliest evidence for eggnog is from 1825, in the writing of John Neal, author and women's rights activist. (Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “eggnog (n.),” June 2024.)

If you’re into such things, back in 1901, a big-brained man explained the etymological assumptions of the OED.

Across the authoritative references, you will read several competing theories:

Theory 1: The “nog” derives from “noggin,” meaning a small wooden mug with an upright handle used to serve alcohol. Under this theory, “Eggnog” simply means “eggs served in a noggin.”

Theory 2: “Nog” comes from East Anglian strong beer, documented in 1693 when Humphrey Prideaux wrote about “old strong beer, which in this country [Norfolk] they call ‘nog.’” This theory suggests Eggnog meant “eggs with strong beer.”

Theory 3: The name is a compression of “egg ‘n’ grog,” supported by early recipes specifically calling for rum, as grog was historically associated with rum drinks.

Regional variations add to the complexity. In Orkney and Shetland, “nugg” or “nugged ale” referred to ale warmed with a hot poker, possibly related to Norwegian “knagg” or Danish “knag.”

Similar milk-and-egg beverages have appeared under various names including egg-pop, custard posset, syllabub, milk punch, flip, “one yard of flannel,” and “auld man’s milk.” A related drink was sack-posset, made with milk, eggs, and either ale or sack (a dry wine from Spain or the Canary Islands).

EGG-NOG, n. A drink used in America, consisting of the yolks of eggs beaten up with sugar and the whites of eggs whipped, with the addition of wine or spirits. In Scotland milk is added and it is then called auld man's milk. — Encyc. of Dom. Econ. (An American Dictionary of the English Language by Noah Webster, 1852)

2. Antedating and Sourcing

You’ve probably noticed another problem with the OED entry: “OED's earliest evidence for Eggnog is from 1825, in the writing of John Neal, author and women's rights activist.” Look I’m an OED respecter, but this is telling in more ways than one. It will take anyone connected to the internet five minutes to find dozens of mentions prior to the 1820s, I’ve mentioned several above.

Others saw the OED’s mistake long before me. Language wizards were discussing it in 2007, yet even the experts missed Attmore’s 1787 mention and recipe. I actually found those old posts researching the errors I found. Attmore’s journal is known, but no one seems to have placed it in the story of Eggnog.

I kept stumbling over claims like the one above, saying Auld Man’s Milk was the true source of Eggnog. Now, I’m no John Hanning Speke, but so far, I’m not convinced. Of course, I’m willing to be proven wrong.

3. Fake News

I’m all for Cherry Tree-style myths. They’re natural, good, and even necessary. But there’s no reason to stretch the truth when it’s so simple to check. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve come across something like this: George Washington’s Eggnog was a thing of legend. He served it to his guests, rich and spiked with rye whiskey, rum, and sherry. He wrote the recipe down, though he left out the count of eggs. A dozen or more, most likely. Cream, milk, sugar, stirred slow and heavy with spirits. Modern Eggnog stays close, adding cinnamon, cloves, and nutmeg.

The folkchain will never counter-signal the American Cincinnatus, that’s something the Eggnog-deniers would do, but the lies aren’t his doing. The supposedly historic Washington Eggnog recipe, multiplied across print and pixels like biblical loaves and fishes, proves to be entirely apocryphal, and it’s not even that old of a myth. The full story’s there if you care to look for it.

A Southern Christmas Tradition

From Attmore’s 1787 observation grew the first documented link between Eggnog and Southern Christmas celebrations. By the early 1800s, this union had become indissoluble. Christmas morning in Southern homes, particularly on plantations, began with the sacred mixing of Eggnog. As men hauled in the Yule log at dawn’s first light, servants assembled the precious ingredients. The grandest families served from ancestral punch bowls—magnificent vessels holding thirty-six gallons, each bearing the weight of generations. The preparation became one thread in the intricate tapestry of Christmas preparations beginning weeks before: the butchering of hogs, the making of mincemeat, the gathering of evergreens. Households carefully accumulated alcohol and dairy products, knowing Eggnog would crown the holiday’s numerous libations.

The Southern Agriculturist Vol 1 Iss 6 (1828-06)

In compliance with your request, I think we may remember, with some sad feelings of regret, the good old past-times of plenty and comfort in Carolina; when we considered it quite a glorious feat, to have our shoulders nearly dislocated by the discharge of an overloaded, old, rusty, plantation gun, to salute the rising sun, and rouse the slumbering household on a cold, merry-Christmas, good morning; and then archly intercept the family, old fashioned, massy silver waiter, crowned with whole bumpers of egg-nog, as the maid-servant was entering the bed-rooms, where our old widowed aunts, our old-maiden sisters, and, perhaps, a half dozen or so first, second, third, and even fourth cousins were all dozing; for, in the good old times of which I am speaking, tradition tells us, it was not considered unfashionable nor stupid, to cousin the third and fourth generation of those who esteemed you as such.

Eggnog served as the South’s liquid handshake, extended to everyone from the nearest neighbor to the most distant traveler. Eggnog-enjoyers weren’t only the landed Gentry. The newspaper record and oral histories show the beverage was enjoyed by all. Even the Civil War’s harsh deprivations couldn’t kill this tradition. Hospital matrons, seeing in the drink both comfort and healing, prepared it for their wounded charges. In army camps, soldiers scoured the countryside for eggs and spirits, desperate to preserve this taste of home during the holidays.

“I have always found eggnog the best thing ever given to wounded men. It is not only nourishing, but a stimulant.” - Kate, The Journal of a Confederate Nurse

The standard recipe by 1815 called for separating six eggs or more, divided between yolk and white. The yolks married first with sugar, then spirits, rum leading the way, though brandy and whiskey made frequent appearances, sometimes joined by Madeira or sherry. Milk or cream provided substance, while beaten whites were gently folded in. Nutmeg or lemon zest crowned the mixture. Hot Eggnog made with warmed milk was a popular variant, as was the single-glass version, where a whole egg was shaken with sugar, milk, and spirits.

Letters of William Gilmore Simms, Volume V—1867-1870

To Frederick Swartwout Cozzens: Charleston, Decr. 19 [1865-1866]. My dear Mr. Cozzens. By the Quaker City, I forward next Saturday to your address, a bottle of Rum, whether Yankee or Jamaica, I cannot tell you, but I am assured that it has been 18 months in cellar. I hope you will find it good & grateful. In making Egg Nog, in our old times, our process was to use equal parts of Jamaica & Cognac. I take for granted that you know, not only the goodness of this beverage, at Christmas, & during the New Year Holidays, but also the proper mode of its preparation.

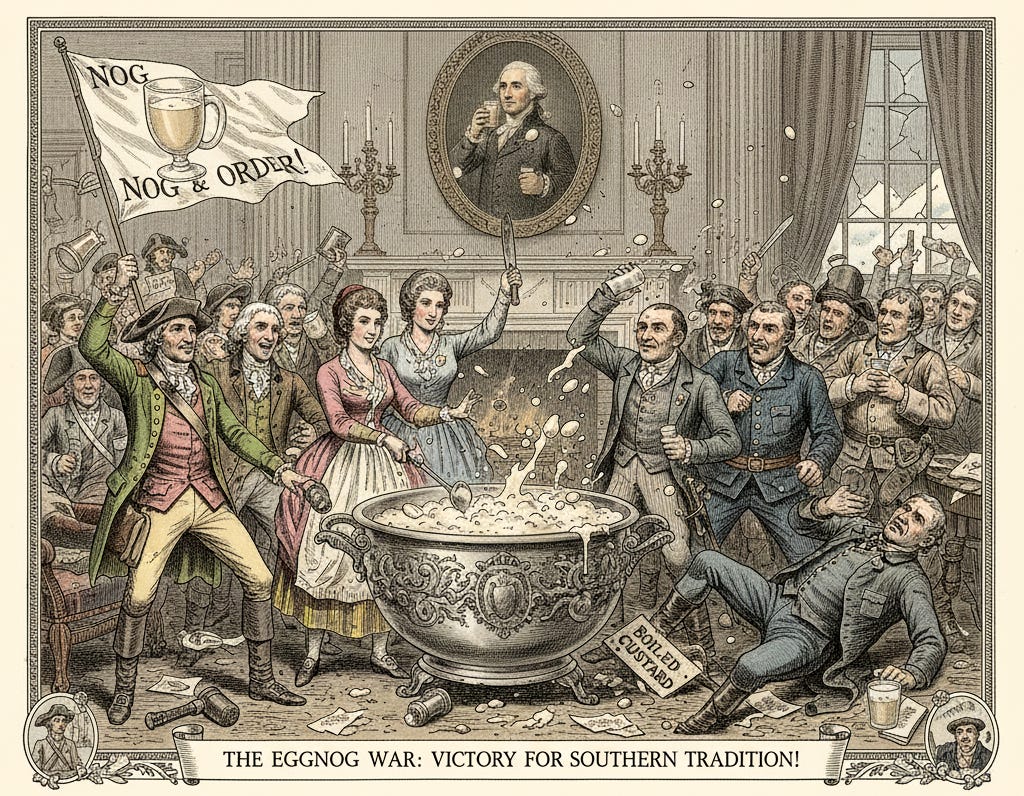

The Haters

The Prohibition regime sought to strangle the venerable custom of greeting Christmas guests with proper Eggnog. Those years produced anemic substitutes like “Boiled Custard,” born in the longhouses of temperance reformers. Today, a different breed of cultural revolutionaries pursue destruction: they melt statues, topple monuments, and engineer demographic decline. These Eggnog-haters, in their contempt for ancestral wisdom, shall receive no Christmas Truce of 1914. One does not negotiate with vandals of heritage.

Nog and Order

The Eggnog Question transcends mere preference. To claim Southern identity while rejecting this tradition reveals one as either a Carpetbagger or, more contemptibly, a Scalawag. And to all others—whether Yankees, Midwesterners, Californians, or simply Americans—Eggnog flows through your cultural bloodstream just the same.

In “The Search for Order in American Society,” Andrew Nelson Lytle discovered what we should have known, traditional cuisine can anchor a civilization. Eggnog remains one of our strongest anchors:

“A traditional cuisine, composed of culinary crafts, the basic ones inherited, does two things to stabilize society. It demands good manners, and this restrains appetite and thus makes for the etiquette of the table, which in turn makes for a respectful savoring of the dishes served, good conversation, and a celebration of a social amity among the diners. It maintains leisure, which gives pause for reflection, upon which the arts and, for the last four hundred years, history had depended. Memory, through recollection, into song, I believe is the classic inheritance the Western world has abandoned in its reduction of man to his physical dimensions. The taste and odor of the family victuals, which has the common taste of a province or region, binds the solitary to the family and the family to a place . . .”

History has rendered its verdict. Eggnog disrespecters were rejected at the ballot box. Come join a rich and creamy inherited tradition that spans centuries and continents. Cheers!

Notes & Recipes

First, I will continue to research Eggnog’s history as it relates to the South. I already have 100+ pages of notes. I doubt I will write a book, but I’ll upload a comprehensive research guide to the archive eventually. Far as I know, there’s no book on Eggnog. The books I’ve seen on Christmas in the South stick to plantations and slavery. They’d have you believe most Southerners didn’t bother with Christmas at all. I have hundreds of quotes mentioning Eggnog from Newspapers in every Southern state; War of 1812, the Texas Revolution, the Mexican-American War, Civil War diaries/journals/books; Travel Narratives; Periodicals; Oral Histories; and every other type of written source. They need to be compiled for the “record.” I also think it’s significant if Attmore’s recipe is the oldest, especially since it’s from North Carolina, a Southern State. Besides the quotes, I need to catalog all the recipes, so we can do some data stuff.

The Columbia Encyclopedia (1950): Christmas—Other American innovations are firecrackers and egg nog in the South.

Reading List (Just a small sample)

Christmas in Dixie during the War Between the States

Bever, Megan L.. At War with King Alcohol: Debating Drinking and Masculinity in the Civil War. University of North Carolina Press, 2022.

Christmas Memories from Mississippi. University Press of Mississippi, 2010.

Christmas Stories from Georgia. University Press of Mississippi, 2005.

Christmas in the South: Holiday Stories from the South's Best Writers. Algonquin Books, 2004.

Coulombe, Charles A.. Rum: The Epic Story of the Drink that Conquered the World. Citadel Press, 2004.

Covert, Adrian. Taverns of the American Revolution. Insight Editions, 2016.

Cure, Karen., Brown, Lois. An Old-fashioned Christmas: American Holiday Traditions. H.N. Abrams, 1984.

Encyclopedia of Southern Culture. University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

Farr, Sidney Saylor. More Than Moonshine: Appalachian Recipes and Recollections. University of Pittsburgh Press, 1983.

Food in the Civil War Era: The South. Michigan State University Press, 2015.

Fowler, Damon Lee. Classical Southern Cooking: A Celebration of the Cuisine of the Old South. Crown Publishers, 1995.

Genovese, Eugene D.. The Sweetness of Life: Southern Planters at Home. Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Glenn, Camille. Camille Glenn’s Old-Fashioned Christmas Cookbook. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1996.

Kane, Harnett T.. The Southern Christmas Book, the Full Story from Earliest Times to Present: People, Customs, Conviviality, Carols, Cooking. D. McKay Co. 1958.

May, Robert E.. Yuletide in Dixie: Slavery, Christmas, and Southern Memory. University of Virginia Press, 2019.

Restad, Penne L.. Christmas in America: A History. Oxford University Press, USA, 1995.

Shanahan, Madeline. Christmas Food and Feasting: A History. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2019.

Slave Narratives

Smith, Andrew F.. Drinking History: Fifteen Turning Points in the Making of American Beverages. Columbia University Press, 2013.

Taylor, Joe Gray. Eating, Drinking, and Visiting in the South: An Informal History. Louisiana State University Press, 1982.

The Civil War Christmas Album. Hawthorn Books, 1961.

The Food of a Younger Land: A Portrait of American Food : Before the National Highway System, Before Chain Restaurants, and Before Frozen Food, when the Nation's Food was Seasonal, Regional, and Traditional: from the Lost WPA Files. Riverhead Books, 2009.

The Letters of William Gilmore Simms

The Oxford Companion to Spirits and Cocktails. Oxford University Press, 2021.

The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America. Oxford University Press, 2012.

The Oxford Handbook of Christmas. Oxford University Press, 2020.

Walter, Eugene. Happy Table of Eugene Walter: Southern Spirits in Food and Drink, edited by Don Goodman, and Thomas Head, The University of North Carolina Press, 2011

1787 Egg Nog

In two clean Quart Bowls, were divided the Yolks and whites of five Eggs, the yolks & whites separated, the Yolks beat up with a Spoon, and mixt up with brown Sugar, the whites were whisk'd into Froth by a Straw Whisk till the Straw wou'd stand upright in it; when duly beat, the Yolks were put to the Froth; again beat a long time; then half a pint of Rum pour'd slowly into the mixture, the whole kept stirring the whole time till well incorporated. (Journal of a Tour to North Carolina by William Attmore, 1787)

Alton Brown’s Aged Eggnog looks interesting.

Auld Man's Milk of Scotland, or Egg-nog of America (1844)

Beat the yolks and whites of six eggs separately; put to the beat yolks sugar and a quart of new milk, or thin sweet cream; add to this rum, whiskey or brandy, about half a pint; put in the whites of the eggs whipped up, and stir the whole gently. It may be flavoured with nutmeg or rind of lemon. (An Encyclopaedia of Domestic Economy. 1844)

Baltimore Egg Nogg

(Large bar glass.) 1 yolk of an egg, tablespoon of sugar, add a little nutmeg and ground cinnamon to it and beat it to a cream.

1 half pony brandy

3 or four lumps of ice

¼ pony Jamaica rum

1 pony Madeira wine

Fill glass with milk, shake thoroughly, strain, grate a little nutmeg on top and serve. (Stuart’s Fancy Drinks, 1896)

Egg Nog

“The recipe below for egg nog would have indeed been a special treat for a soldier even at Christmas. Unfortunately, they often had to make do with a far less rich mixture.”

4 egg yolks

4 Tbsps sugar

1 cup cream (whipping)

1 cup brandy

¼ cup wine

4 egg whites

A little grated nutmeg

Beat the egg yolks until light then slowly beat in the sugar, cream, brandy and wine. Whip the egg whites separately and then fold into the other ingredients. Sprinkle with the nutmeg to serve. (The Civil War Cookbook by William C. Davis)

Egg Nog—As Enjoyed by Robert Morris

5 egg whites

¼ tsp salt

5 egg yolks

2 tsp vanilla

¼ cup sugar

Nutmeg to suit

Put egg whites in a small wooden mixing bowl and beat them to a soft fluffy peak. Stir in the egg yolks and beat again. Add the sugar, salt and vanilla. Beat a third time. Set aside to chill. When thoroughly chilled, sprinkle with nutmeg and serve. (Historical Christmas Cookery by Robert W. Pelton)

Old Virginia Eggnog

Twelve eggs, 1½ pints best whiskey, 3 gills best rum (Cognac brandy, fair substitute), I well-rounded tablespoon granulated sugar to each egg, 1 quart of milk or cream, beat the yolks light, add sugar and beat light, add whiskey, rum, milk, beat light, put in whites beaten to a froth. This recipe is fairly mild. For men increase liquor to 1 quart of whiskey, I pint of rum. One drop of oil of cinnamon improves this for some people. Never add liquor after cream or milk; this will ruin your eggnog.

Sherry Egg-Nog—Von Steuben’s Christmas Concoction

1 egg yolk

1 tbls sherry wine

1 tsp sugar

¾ cup cold milk

Pinch of salt

1 egg white, lightly beaten

Nutmeg to suit

Put the egg yolk in small wooden mixing bowl and beat until thick and lemon colored. Stir in the sugar, salt and sherry wine. Add the cold milk. Pour into a shaker or tightly covered canning jar. Shake well. Fold in the fluffy egg whites. Pour into glasses. Sprinkle with nutmeg. Serve cold. (Historical Christmas Cookery by Robert W. Pelton)

St. Francis Street Methodist Episcopal Church Eggnog (Mobile, Alabama. 1878)

To each egg, allow one small wine glass of brandy, one tablespoonful of sugar; beat the whites and yolks separately. After beating the yolks well, gradually add the sugar, then the brandy; also allow about three wine glasses of rum to about one dozen eggs; pour in the milk, as much as you like—say a quart to a dozen eggs and last, stir in the whites when they are as light as they can be beaten. (The Gulf City Cook Book)

Tally Simpson’s 3rd South Carolina Eggnog

Separate 1 dozen eggs, and beat whites and yolks separately. Then for each egg, mix 3/4 cup of rum or whiskey and the same amount of boiling water with 1 tablespoon of molasses. Mix thoroughly; then stir in the beaten eggs, stirring constantly to prevent curdling. Then stir in 7/4 cup of milk, and serve. (A Taste for War: The Culinary History of the Blue and the Gray by William C. Davis)

Virginia Egg Nogg

Eight eggs, one tablespoonful of pulverized sugar to each egg, one wine glass of rum or brandy to each egg. usually mix rum and brandy, half a pint of milk. Beat eggs separately and very light, keeping out a portion of the whites to put on top. Sugar and eggs are beaten together. Stir this into the milk, next the rum and brandy, and beat the white of the eggs. Much depends upon the manner in which the ingredients are put together. (Recipes Old and New. Collected by Mrs. Charles Marshall for the benefit of the Confederate relief bazaar. April, 1898.)

The Tennessean (1941-12-28)

Traditional as refreshments on New Year's Day is that rich and luscious twin offering of eggnog and fruit cake. A gourmet gift from the famed hospitality of the Old South, eggnog is still the accepted “right thing” to bring forward for every guest who calls to pay his or her respects on New Year's Day. This thick, custardy whip must of course be eaten with a spoon.

Very thoughtful piece. You did miss “coquito” the Puerto Rican eggnog which I happen to have shared a recipe for in my last post. The addition of coconut cream works quite well in the mix. Thanks for such an exhaustive exploration, cheers, M

Gonna be sharing this with my Southern Eggnog Respecting Husband.