Economic Problem of the Southeast

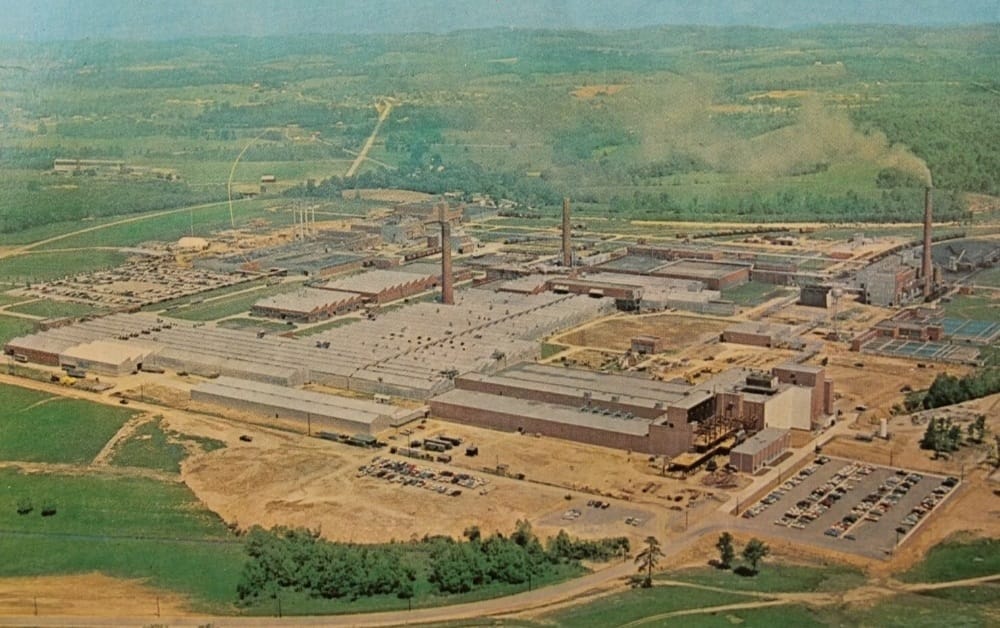

The remains of the Dutch-owned American ENKA plant cover the land in Lowland, Tennessee, like a steel skeleton picked clean. The smokestacks rise red against the sky, two of them, maybe a hundred fifty feet high. The parking lot has cracked enough to let a little wilderness in, an archipelago of grass and weeds pushing up through old asphalt. Grackles squawk rustily atop rust-red I-beams, some peeling back like pencil shavings to raw metal.1

The plant opened in 1947 to manufacture rayon for tire cord. Wood-pulp alchemy of a time that believed chemistry could reorder the world. Three years later bullets were flying. Striking C.I.O. textile workers, young men from the East Tennessee hills—tall, spare, quiet as fence posts—shouldered rifles, and fired on cars approaching the gate. Forty-seven bullets struck one Ford sedan. Violence flared, then cooled. Decades later, the chemistry moved elsewhere and the plant left to the elements.2

The story is not unique.

My Grandpa drove the tow motor at Oscar Mayer in Goodlettsville for near twenty years until they shut it down. Grandma worked the security shack at Pirelli Tires. Other kin punched the clock in the shirt factories and shoe plants that once dotted Middle Tennessee. A Great-Great-Grandpa kept the blades sharp for a cedar mill in Mobile and was sent to Lebanon because the pencils were made there. First time I ever saw a hijab was twenty years ago, on shift at the Nashville Dell plant. Once disconnected from the land, families moved in small arcs shaped by mills, plants, shifts, and the sound of whistles.

Some plants stayed long enough to anchor a county. Many did not. Kannapolis lost its textile empire. Pine Bluff lost a paper operation that once ruled the skyline. Gadsden lost steel. Lake Charles lost two chemical lines. Rock Hill shut a tire cord division. Spartanburg, Baton Rouge, Rome, Danville—whole blocks hollowed after closures. A factory in Salisbury just closed. A packaging plant in Alabama. A parts supplier in Mississippi. A plastics outfit in Florida. In Tennessee the GM battery layoff in Spring Hill sent seven hundred home for a season.

Across town a banner on a fence promises thousands of new jobs. Local newscasts talk about “the future of American manufacturing.” Politicians call it proof that they care about the community.

The work is real. The wages are real. The chance to make an honest living. But the rhythm is familiar, and familiarity is its own kind of instruction. The South has lived long enough with these waves to know that industry arriving with flourish may leave when the larger order changes its mind. A plant opens. A plant closes. The town learns to grieve in unemployment offices, job fairs, and church parking lots. Another banner goes up on another fence.

This rhythm did not begin with rayon or batteries. It runs back through textiles, through timber, through all of it.

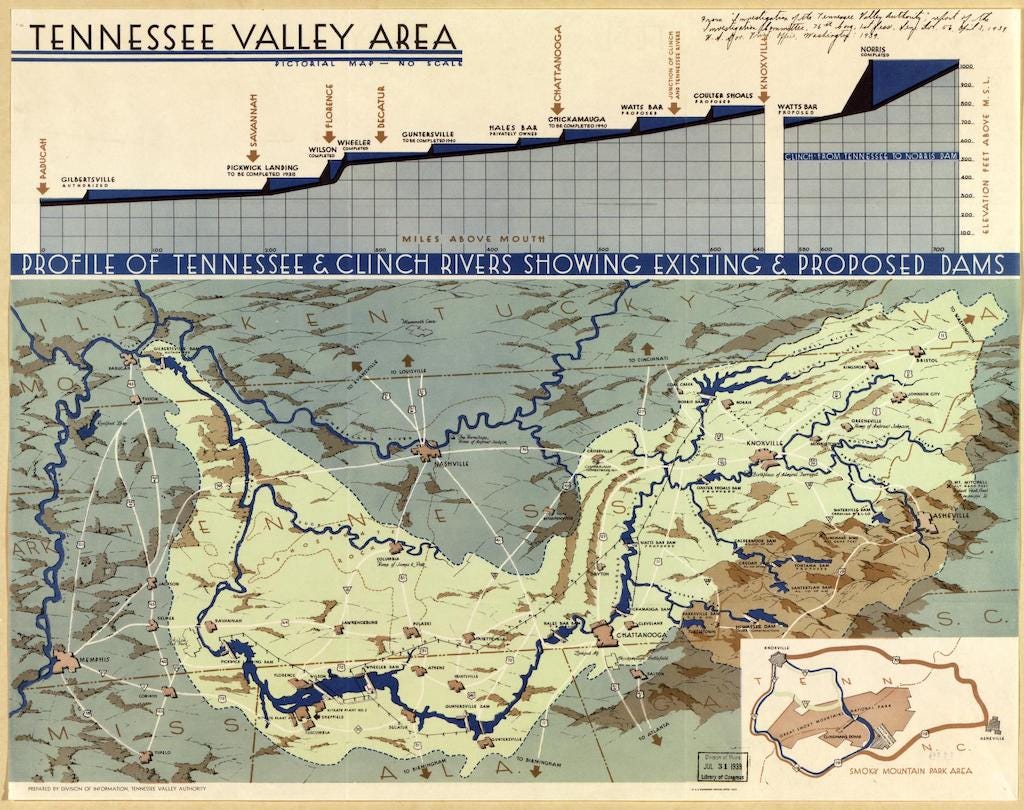

Stand below one of the old TVA dams on an autumn afternoon and watch turbines turn falling water into light and dividends. You might forget, looking at that clean geometry of poured government ambition, that FDR spoke it into existence in 1933, a few years before he stood at Warm Springs in 1938 and called the South the “Nation’s No. 1 economic problem.”3

He saw a region whose wealth had long flowed away from its people. A region held in patterns shaped by others. A region whose natural abundance did not translate into local prosperity. His solution was federal—TVA, REA, WPA, CCC—the whole alphabet. Roosevelt’s framing became part of the vocabulary of the New Deal. Though, ever since Appomattox critics have cast the South as a standing American problem.

Eleven years after Roosevelt’s declaration, Anne E. Hulse and Patrick J. Deturo published a study in the Harvard Business Review titled “Economic Problem of the Southeast.” They wrote with the calm authority of mid-century business science. Their purpose was diagnosis and prescription. Their tone was measured, urgent, optimistic. Their audience wasn’t the South.

Hulse and Deturo framed the South as a domestic Marshall Plan waiting to happen. Europe received billions in reconstruction and recovery funds while businessmen hurried to secure contracts in foreign markets. A vast potential domestic market sat unattended at home.

“If every inhabitant of the Southeastern section of the United States were to attain a standard of living comparable to the average for the balance of the nation, there would be created an additional demand for at least $13 billion of goods and services annually.”

Their working definition of the Southeast covered eleven states: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia. Texas and Oklahoma were excluded. Those states, they wrote, had little in common with the Old South, and to include them would obscure the genuine problems confronting the region.

Charts and tables fill the pages. It is all very neat. I assume their numbers were not wrong. A number is clean, brings order to a region that resisted it. The South held a fifth of the population but earned a tenth of industrial wages. School terms ran short. Children left class for fields, for mills. Workers stayed on past sixty, past sixty-five, bodies bent, joints stiff. Farm income stayed low. Diets suffered. Families lived at the edge of necessity. And none of the men were leadership material. Backwards, they called it.

“The South has never experienced the influx of European labor which played such an important part in the industrial development of the North and the West.”

Many jumped on the Hillbilly Highway. One-seventh of Southern servicemen did not return after WWII. The region never experienced a European immigration influx on the scale of the North and West. The South was never a nation of immigrants. Between 1920 and 1930, a hundred thirty thousand more people left the region than entered each year. During the war years, the average net loss climbed to a quarter million annually. Over half of those who left were between fifteen and thirty-four.

The cure, Hulse and Deturo believed, was industry. More plants, deeper capital, longer schooling, and outside management until the region could stand on its own.

“Only when the South succeeds in producing on a scale comparable to that of other sections of the country will it be able to enjoy a high standard of living.”

The region which the charts describe as “lagging” was, in 1940, already well along the road to national assimilation. Radios and mail-order catalogs had carried the gospel of mass consumption into the backwoods. The old loyalties were already yielding to the new creed of Mobility.

The authors projected convergence. The numbers, for a time, cooperated. By 1978, Southern per capita income reached 88% of the national average. Spring Hill got Saturn. Smyrna got Nissan. Georgetown got Toyota. Research Triangle filled with labs. Atlanta pulled in corporate headquarters. Charlotte built bank towers forty stories high. Progress, they call it. But new industry often comes with strings thicker than the hawsers on those Liberty ships.

Many jobs that did stay—poultry plants, meatpacking, construction—now rely on foreign labor. From a local worker’s view, this feels like a double bind: your father’s union-ish factory job left for Mexico or China, and the new jobs in town are lower-wage, harder, and staffed by people who you can’t even shoot the breeze with. The 1949 framework grappled with none of this.

But read past the tables and charts, past the policy prescriptions, and something else emerges—abstractions and a place identical to everywhere else.

“The South distrusts and resents industrial installations when all the operating decisions are made in main offices located elsewhere or by men sent in whom it regards as aliens.”

Abstraction erases the very things that give a place its meaning. A region becomes a zone, a section, a market. A community becomes a labor force. A farm becomes an inefficient use of acreage. A home becomes a unit of consumption. A tradition becomes a barrier to progress. The people become inhabitants, units in tables. A place that lives by particular attachments becomes, in the hands of experts, a problem to be solved. When a place is interpreted through aggregated data alone, its history disappears.

The authors list the region’s four “great resources”: a young population, abundant minerals and timber, adequate energy, and productive land. They are not praising its blessings. They are identifying inputs. Their admiration is functional. They speak with the confidence of engineers describing a machine that has not been operated at full capacity. What they cannot capture with their diagrams are the costs such a view imposes on a place. They assume growth is neutral.

Education is viewed solely as preparation for industrial work. They see children as future cogs in a national system of production. They never ask what education means for a community beyond the labor market, what it offers beyond wages. They measure the success of schooling by its ability to produce technicians and managers. They do not consider that education might also safeguard memory and shape civic life.

But this is heresy to the Church of Gross Domestic Product. In that denomination, the highest sacrament is line go up. A man becomes human only when his labor passes through the blessed machinery of wages, taxes, and corporate profits, there to be sanctified by economists and returned to him in the form of rayon shirts purchased with one-click interest free payment plans.

What is never asked in these liturgies to Progress is what sort of life the South is to lead when it has at last matched the national average of Amazon deliveries per household.

“While other areas less favorably endowed have improved their economic position by making use of Southern resources, the South receives what in a very real sense is only partial payment for its rich natural wealth.”

Agrarian thinkers had named these blind spots long before 1949. They did not deny the South’s poverty. They argued that the cure being offered—unchecked industrial growth, absorption into the national economic order, the transformation of farmers into factory hands—would strip the region of something hard to name and harder to recover. They believed memory was a form of capital and that breaking a region from its past in the name of progress left it hollow. They believed that economies organized at a scale too large for human life would always extract more than they returned.

“From all indications the Southeastern region of the United States appears to be at the point where it is ready for a full-scale industrial expansion such as it has never experienced in its entire history. Basic conditions have improved during the war, and the South is stirring.”

The South built a Sunbelt economy. Foreign auto plants arrived in the 1980s. Amazon fulfillment centers followed. EV battery megasites rise now from Tennessee limestone. Income converged. Population reversed its outflow, by the twenty-first century, the South gained more people than it lost. The region that once exported its young now imports workers from other states and other nations.

While researching for this piece, I messaged a more knowledgeable friend about my split mind on the subject and if he knew of industry “done right.” He wrote back: “You have to make a decision to not maximize scale, dollars, etc. There are lots of smart guys who went to some fancy school and returned to their small town to run a smaller business that employed the entire town. Not enough people appreciated that, and now lots of them are gone. But you can run a smaller manufacturing business and do okay. All the fat of those companies has just gone into Private Equity pockets. I see it every day. Tragic.”

Related

“LABOR: Trouble at Lowland.” TIME, July 3, 1950.

(1) National Emergency Council. Report on Economic Conditions of the South. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1938. (2) Franklin D. Roosevelt, Message to the Conference on Economic Conditions of the South. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. (3) “National Affairs: Problem No. 1.” TIME, July 18, 1938.

Damn, Chase, this is excellent.

Outstanding, Chase. Thanks. "A region becomes a zone..." That's just one of many perfectly-put phrases.

This book has many chapters: Decades of regional decimation in the violence of war and its cataclysmic aftermath; the painful opportunistic pounce of (and then resource extraction by) northern industrial (and now global) capital; acceleration of the atomization via financializing monetary policy and public-debt-financed infrastructure; institutionally-imposed cultural memory-holing. All of it pushing and pulling away from dignity, community, and regional autonomy.

I take it as a reason for great optimism that people are starting to see that all this dégringolade wasn't inevitable—that it's been a choice imposed on people everywhere (not just the South) by technocratic planners. A few hundred years from now, I expect our great great great great grandchildren will look back on this mindset as a weird (and hopefully briefly-lived) insanity.