Christmas 1779

December 25, 1779. The city of Nashville does not exist.

No streets. No bachelorettes. No Opry. No Californians. A limestone bluff above a cold brown river. A sulfur spring the French had traded at for decades. A handful of men in three-sided shelters open to a fire set against the wind.

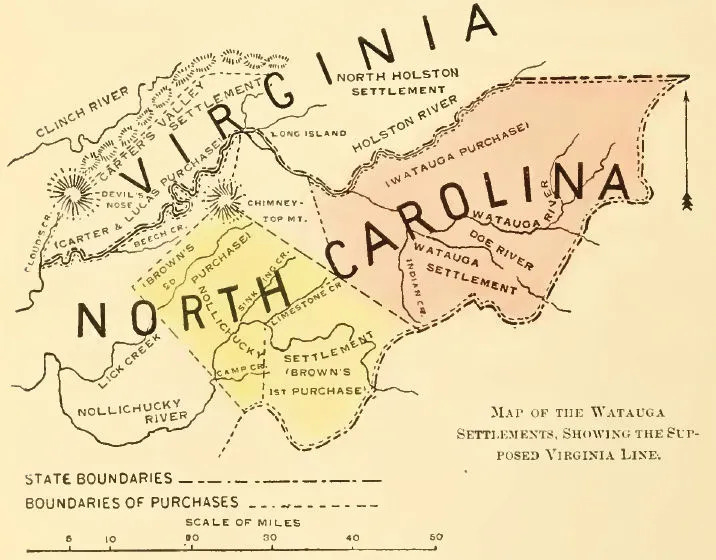

James Robertson led them here. Thirty-eight years old. A veteran of the Chickamauga Wars. In October, when the mountain laurel had gone to rust and the first hard frost silvered the Watauga Valley, he gathered between two hundred and three hundred men and boys and pointed them west through the Cumberland Gap. They drove horses and cattle and sheep. Horses scattered. Cattle balked at creek crossings. Sheep spooked at wolves. A man alone could cross thirty miles of open country in a day. A man driving livestock across the Cumberland Plateau counted himself fortunate to make eight.

The route wound north through the Gap. This narrow saddle in the Appalachian spine bore Thomas Walker’s name from 1750; Cherokee, Shawnee, and buffalo had beaten the trace for generations. All westward movement funneled through that wind-scoured notch. Mist clung in the hollows past midday. From there they descended into Kentucky, down toward the Barren River and on to Mansker’s Station. Kasper Mansker had hunted the basin for a decade. He knew every trace between the French Lick and the Ohio. He guided them south.

Amos Heaton left the Holston settlements around the same time. On Christmas Eve, they camped near White’s Creek within sight of the bluffs. The Williams and Buchanan families followed the headwaters of the Cumberland westward. They arrived to find twenty-five men already there. Some huddled in half-face cabins open to a fire; others hacked at the ground to plant corn for Virginia’s bounty laws. By Christmas morning, fragments of several parties converged.

Meanwhile, 985 river miles east, another party sat trapped in ice.

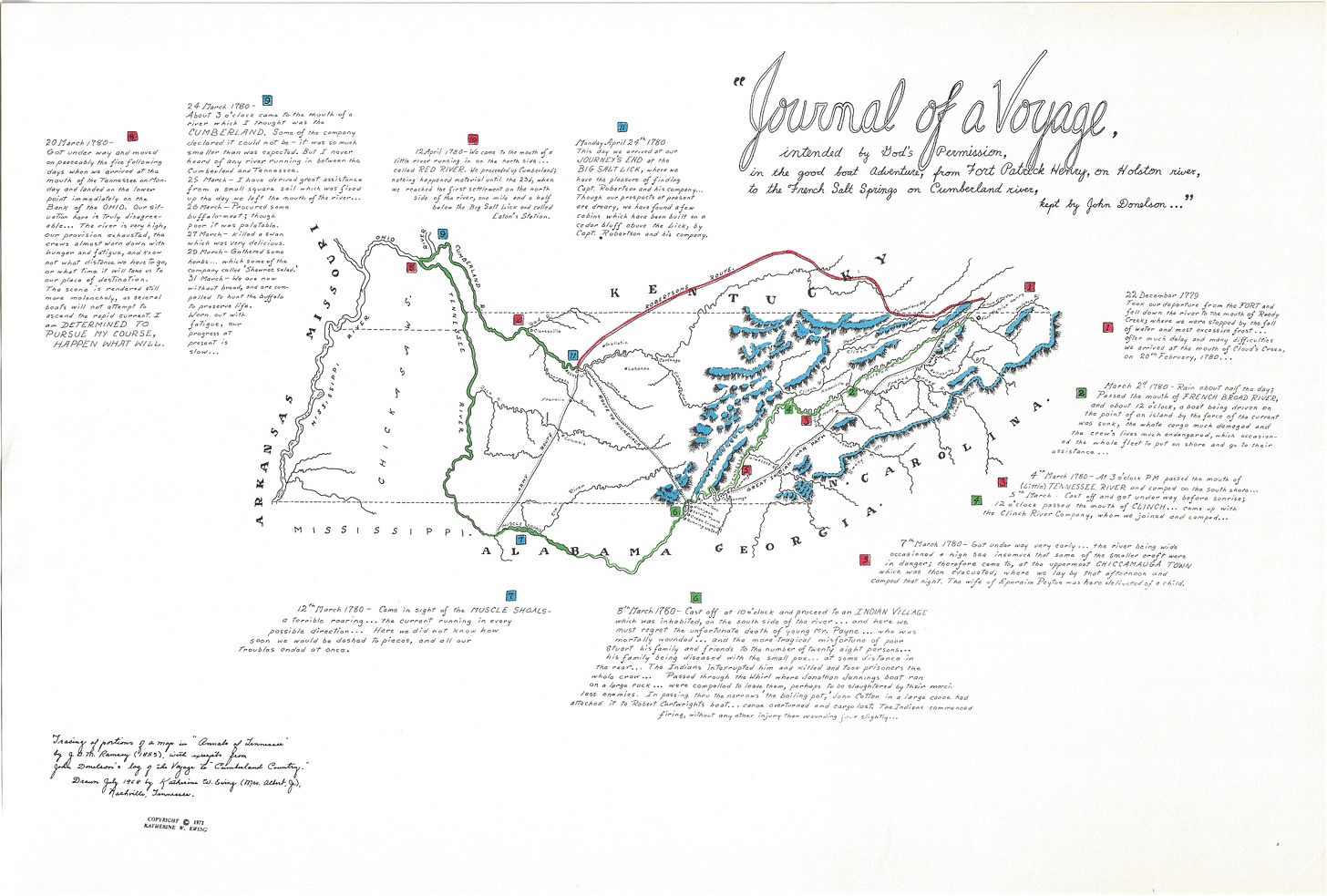

At Long Island on the Holston, John Donelson spent the autumn building a flatboat. A hundred feet of deck. Twenty feet across. He christened it Adventure. Donelson was fifty-four, a county surveyor and land speculator, a former member of the House of Burgesses chosen to lead the families by water. That summer, his son Johnny married Mary Purnell. The sixteen-year-old bride saw the passage as a wedding trip.

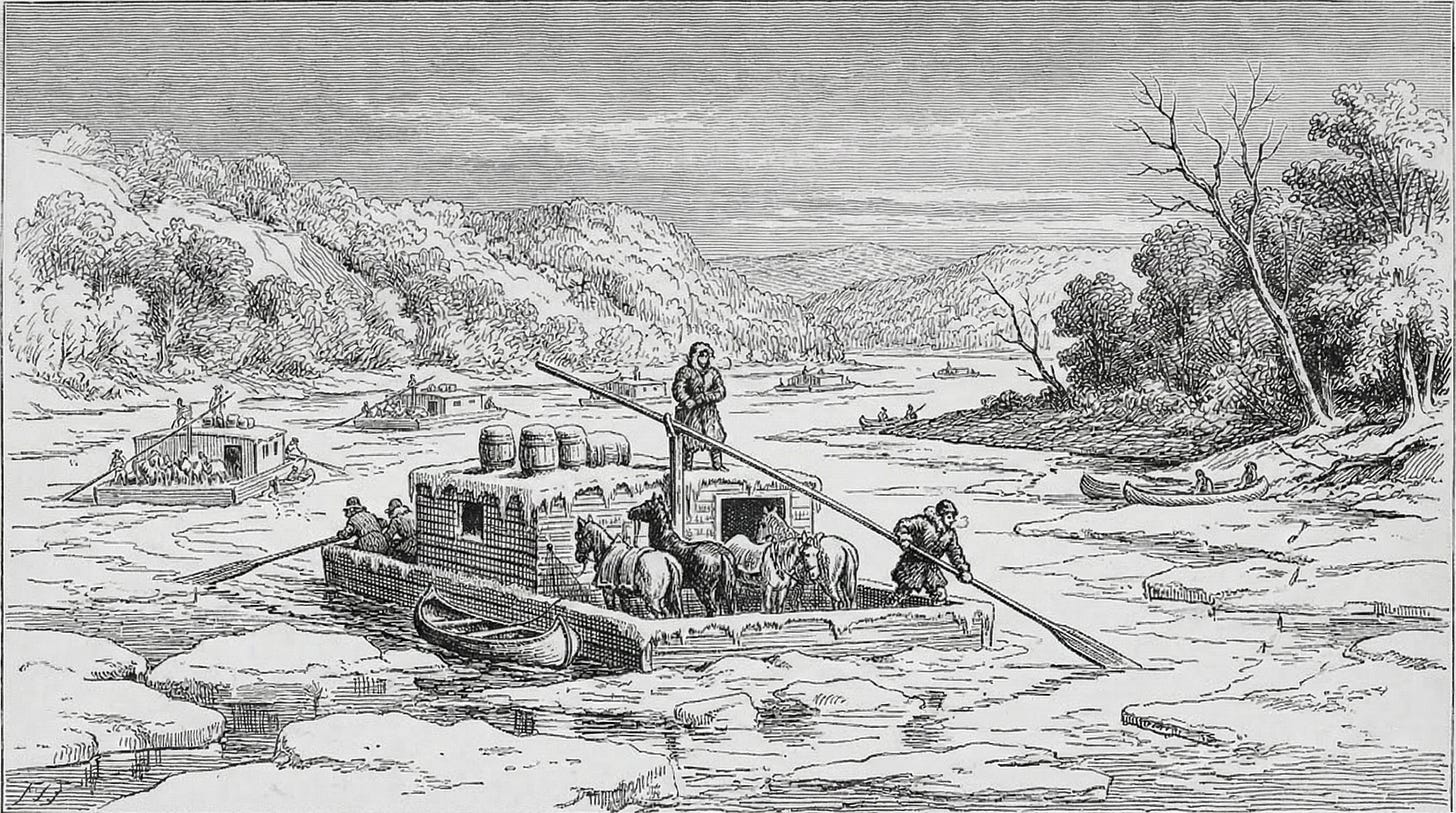

The Donelsons stowed household goods and slaves. They packed silverware stamped with JDe. Charlotte Robertson brought her children to rejoin James at the French Lick. The Adventure served as flagship for thirty vessels—flatboats and pirogues and dugouts—carrying several hundred souls. On December 22, 1779, after the families had boarded the flotilla, they cast off from Fort Patrick Henry.

They did not get far.

At the mouth of Reedy Creek, the water had dropped. The cold sharpened. Three days out, the hulls ground into the silt. Ice crept along the gunwales and held. Rope stiffened. Wool froze. Fires failed. Men went ashore for wood with rifles in their grip. Children cried, quieted, cried again. Flour was counted. Firewood too. The river skinned over.

They would not move again until February.

Christmas Day broke cold over the Cumberland. Robertson held the limestone heights. Heaton’s party lay at White’s Creek. The Williams and Buchanan families slept in scattered lean-tos. A thousand river miles east, the Donelson boats held fast in the Holston ice. Snow covered the ground and stayed. Sap locked in the wood. Trees split through the night, the sound carrying. Years later, Mary Purnell Donelson recalled cattle lying down and never rising. Turkeys froze on the roost and fell, bodies thudding below.1

Further Reading

The Cumberland Settlements–Annotated Bibliography

Journal documenting the 1779-1780 river voyage of Col. John Donelson

Sources

Arnow, Harriette Louisa Simpson. Flowering of the Cumberland. Macmillan, 1963.

Arnow, Harriette Louisa Simpson. Seedtime on the Cumberland. Macmillan, 1960.

Barnes, Katherine R. “James Robertson’s Journey to Nashville: Tracing The Route of Fall 1779.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 35, no. 2 (1976): 145–61.

Henderson, Archibald. “Richard Henderson: The Authorship Of The Cumberland Compact And The Founding Of Nashville.” Tennessee Historical Magazine 2, no. 3 (1916): 155–74.

Snyder, Ann E.. On the Watauga and the Cumberland. Publishing House M.E. Church, South, 1895.

Spence, Richard Douglas. “John Donelson and the Opening of the Old Southwest.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 50, no. 3 (1991): 157–72.

Stealey, John Edmund. “French Lick and the Cumberland Compact.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 22, no. 4 (1963): 323–34.

On January 1, 1780, the Cumberland froze solid. Robertson drove his livestock across the ice and began building the settlement they named Nashborough, for Francis Nash, a North Carolina brigadier killed at Germantown. The Holston ice yielded on February 13. The Adventure began a passage through current and sickness and attack. By April, thirty-four were dead or taken. The overland party lost none. On Monday, April 24, 1780, the boats arrived at the French Lick. They met the Robertson party with jubilation.

Powerful imagery of a Christmas that feels like a world away, but yet is not all that far removed from us in the grand scheme of history.

Merry Christmas to you and your family.