Book-Madness on the Road from Richmond

In October of 1949, Bernard Mannes Baruch walked into the Virginia State Library in Richmond with letters. One hundred fifty-two of them, written in a hand any student of the War would recognize, the neat, right-sloping script of Robert E. Lee. They were addressed to Jefferson Davis between 1862 and 1865, dispatched from field tents and hurried through the lines. Mr. Baruch, seventy-eight years old and among the richest men in America, presented them as a gift.1

His father, Dr. Simon Baruch, a Jewish immigrant from Prussia, had been a surgeon under General Lee. He had operated on a church house door laid across two barrels at South Mountain, worked two days without sleep at the field hospital in Black Horse Tavern after Gettysburg, been captured three times, paroled three times, came home to Camden on crutches to find his practice gone and the state under military rule, and went out on the occasional white robed night ride.2

Bernard Baruch left South Carolina in 1881, went to Wall Street, traded sugar stocks in 1897, made millions, purchased 17,000 acres of former rice plantations near Georgetown in 1905, Hobcaw Barony, where he would later host Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt and George Marshall. Between 1916 and 1946 he chaired the War Industries Board, advised Woodrow Wilson in Paris, counseled Harding and Coolidge and Hoover and Roosevelt and Truman on matters of state, earned himself the nickname “The Lone Wolf of Wall Street” and enough fame that tourists in Lafayette Park photographed him on his bench feeding pigeons. He had never lost the accent of Camden, South Carolina. He had never stopped whistling that catchy tune.

The librarians accepted the gift. The letters went into the vault. They arrived late, as Southern things often do. Not late by days but by decades. No one asked, at least not aloud, how Robert E. Lee’s confidential wartime correspondence to the President of the Confederate States came to rest with a financier in New York City, eighty-four years after Richmond burned, eighty-four years after the last Confederate train left the capital under a bruised April sky, eighty-four years after a young aide decided that papers might survive if they shared a trunk with his shirts.

“To me, the memories of the great southern heroes like Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson are almost living figures because of what I heard my father and others repeat to me in story and song.” - Bernard Baruch

The last time those letters had been in Richmond, the city was burning.

Sunday morning, April 2, 1865. A messenger entered St. Paul’s Episcopal Church during the eleven o’clock service and handed a paper to the sexton. The sexton walked the aisle to the President’s pew. Jefferson Davis read the dispatch and rose. He walked out, down Ninth Street to his office. The congregation watched him go.

Lee’s words: “I think it is absolutely necessary that we should abandon our position tonight.”

Four o’clock—the government announced its evacuation. By nightfall, clerks burned documents in the streets. Staff members swept Davis’s desk into trunks—letters from generals, calling cards, official records, private correspondence.

The presidential train departed around eleven. Judah P. Benjamin rode with Davis. George Trenholm passed around peach brandy. John Reagan whittled a stick.

By morning, nine-tenths of the commercial district had burned, eight hundred buildings, twenty blocks. Raphael Semmes scuttled the James River Fleet after midnight. The explosions shook houses forty miles away. Gutters ran with whiskey. The arsenal exploded before dawn. When Union cavalry rode in, Mayor Mayo surrendered ashes.

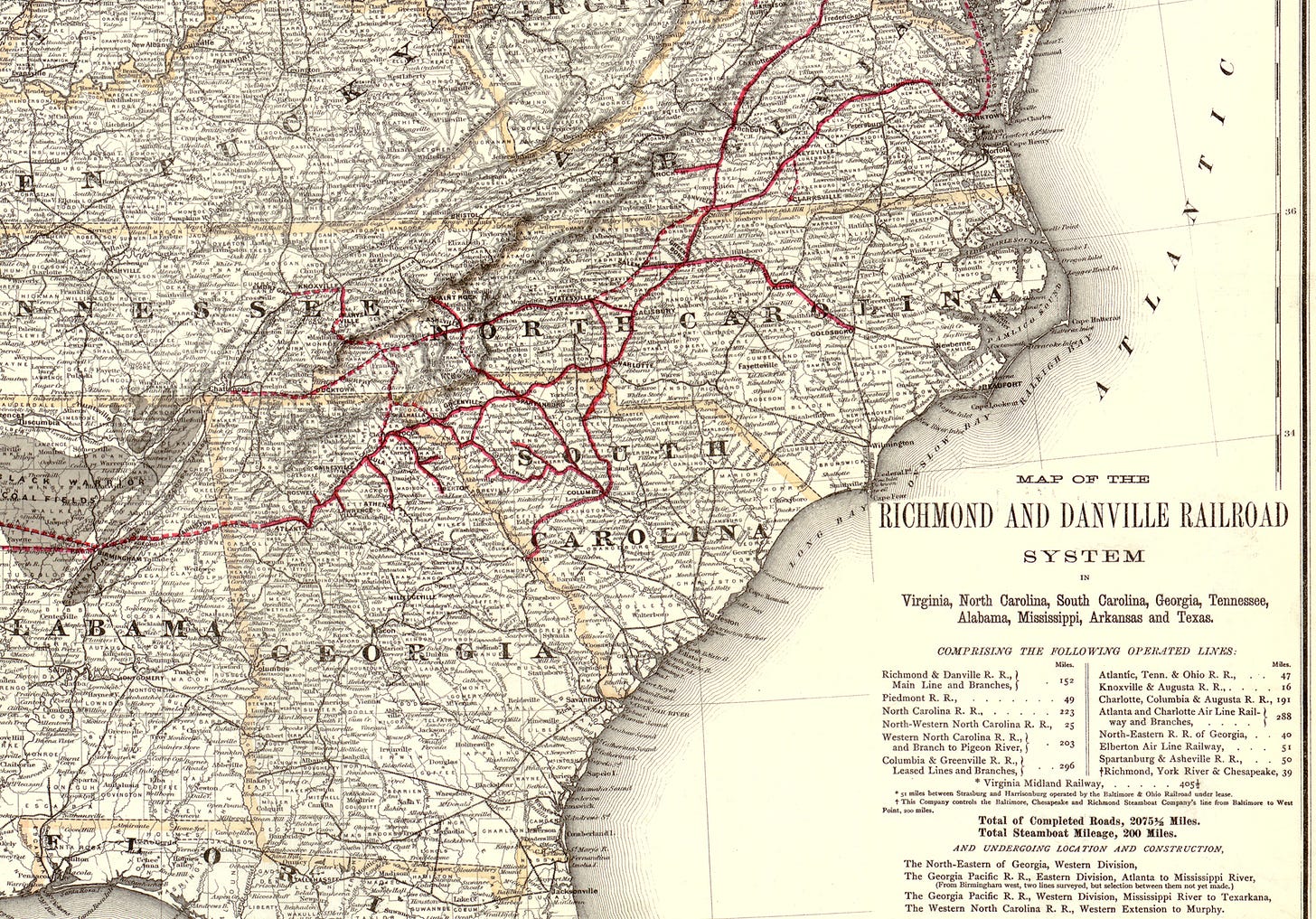

Somewhere in the baggage that fled south lay Lee’s dispatches to the President. Danville, Greensboro, Charlotte, Irwinville, Waldo. Five years passed. When the letters surfaced, they belonged to a private collector.

The man who should have been guarding those papers was not in Richmond that Sunday. Burton Harrison, twenty-seven, Davis’s private secretary since February 1862, had left days earlier escorting Varina Davis and the children south.

Davis gave his wife a pistol and showed her how to load it. “You can, at least, if reduced to the last extremity, force your assailants to kill you.” Their son Jeff begged to stay with his father. They left anyway. Harrison rode with them. The President’s family, his responsibility. The President’s papers, left to clerks.

Yale, 1859. Skull and Bones. Yale Literary Magazine. Mathematics at the University of Mississippi. Then the war. Three years managing Davis’s correspondence. Now Harrison was in Georgia. The papers were in trunks on a train.

May 10, 1865. Union cavalry caught the Davis party near Irwinville, Georgia. Harrison watched the Federals seize the President. “The business of plundering commenced immediately after the capture.”

Harrison spent the next year in federal prisons, Old Capitol Prison in Washington, then Fort Delaware. He studied law with books sent by Yale classmates. Released in 1866, he moved to New York, passed the bar, began building a practice. In 1867 he married Constance Cary, one of the three cousins who had sewn the first Confederate battle flags in 1861. Constance became an author. Their sons would lead the Southern Railway and govern the Philippines.3

The trunk remained in Georgia. Mrs. Robertson shipped it north in 1866. Harrison received it. He did not open it. It sat in storage. Years passed. Jefferson Davis wrote requesting the return of his papers. Harrison did not respond. Davis wrote again. Silence.

Many Confederate records were captured—boxes and barrels seized in Richmond, Charlotte, and along the retreat—and were forwarded to Washington. The War Department established the Archive Office in July 1865 under Francis Lieber to hunt for evidence against Confederate leaders. Lieber sorted through thousands of documents: War Department files, State Department correspondence, Treasury accounts. What the federal government seized became the foundation for the Official Records. What Harrison kept in New York remained unknown.

Harrison was not the only former Confederate remaking himself in Manhattan. Colonel Charles Colcock Jones Jr., of Savannah, Georgia and the Confederate artillery, arrived in New York in 1866, the same year as Harrison. Both practiced law. Both moved in circles of former Confederates.

Sometime around 1870, the Lee dispatches passed from Harrison’s possession into Jones’s collection.

Charles Colcock Jones Jr. collected the way some men drink, not for taste alone, but because they cannot stop. Son of a Presbyterian minister, Jones had graduated from Princeton in 1852 and Harvard Law in 1855. Mayor of Savannah in 1860. Lieutenant colonel of Confederate artillery at the Siege of Savannah in 1864. The war ruined him financially.

Jones collected: autographs of every signer of the Declaration of Independence, including Button Gwinnett’s, one of the rarest American signatures; more than twenty thousand prehistoric artifacts from Georgia’s Indians; colonial imprints, maps, manuscripts; bound volumes of Confederate papers—letters, orders, dispatches; “foremost among them,” one inventory noted, “several hundred letters from Robert E. Lee to Jefferson Davis.”

In November 1875, a slim package arrived at Scribner’s Monthly. Inside was the transcript of a letter from Lee to Davis, dated August 8, 1863, offering his resignation after Gettysburg. The sender was Charles C. Jones Jr. When pressed for authentication, Jones refused references but supplied his law partner’s name and mentioned his authorship of Antiquities of the Southern Indians. Regarding provenance, he offered no clue. Scribner’s published it in February 1876 as “A Piece of Secret History.”

Davis saw the resignation letter in print and wondered how it had escaped his files. Major William T. Walthall, gathering materials for Davis’s memoirs, traced the leak to Harrison. In October 1876, Walthall and Harrison crossed the East River to Brooklyn and arrived at Jones’s brownstone on Clinton Street. Jones produced Harrison’s trunk and claimed the Lee letters had never been inside it—he had copied the resignation letter from a Richmond collector named Captain James O’Donnell. No one ever found O’Donnell.

Jones returned to Georgia in 1877, settled at Montrose near Augusta. He published nearly a hundred books, pamphlets, and articles. When Jefferson Davis died in December 1889, Jones delivered the memorial address in Augusta’s Opera House.

Jones never explained how he had come to possess Lee’s dispatches.

Charles “The Macaulay of the South” Jones died on July 19, 1893, at Montrose, his health broken by Bright’s disease. He left a widow, a historian son, and a collection his estate could not afford to keep. The books Jones had spent decades gathering began to migrate. Wymberley Jones De Renne came to Montrose between 1891 and 1893. The two men shared a surname and a state.

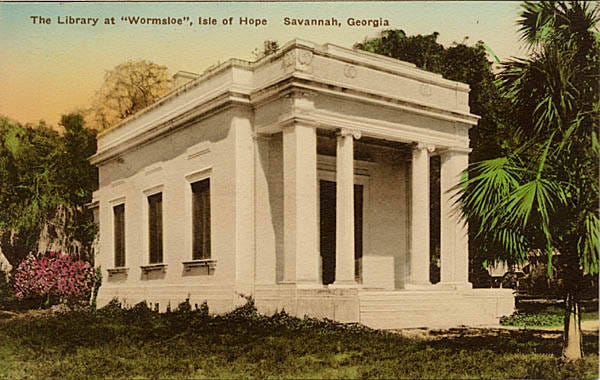

W. J. De Renne’s father had been a collector. His mother had assembled a Confederate collection that Douglas Southall Freeman would later call “second to none in the country.” He had returned to Georgia after years abroad, educated in France and Germany, where he acquired a dueling scar after joining the Saxonia Corps at the University of Leipzig. He came home to Wormsloe, the family estate outside Savannah.

Jones needed money. De Renne had it. The Lee dispatches changed hands. The price is not recorded, but years later De Renne insured them for ten thousand dollars.

Noble Jones arrived in Georgia with James Oglethorpe in 1733 and received five hundred acres on the Isle of Hope. He intended to raise silkworms. The venture failed. The name persisted: Wormsloe. Wymberley’s father, George Wymberley Jones De Renne, had been a collector since the 1840s. Then Sherman marched to the sea. The library did not survive. After the war, the elder De Renne began collecting again. He died in 1880, the library partially rebuilt. His widow Mary continued, focusing on Confederate materials, including the original vellum manuscript of the Confederate Constitution, signed by all the delegates.

Wymberley inherited the estate. By the time he acquired the Lee papers from Jones, he had resolved to surpass his father’s collection. Within two decades, he assembled more than four thousand items relating to Georgia history, which contemporaries called “the most complete private state historical collection in existence.” In 1907, he built a library to house it. Fireproof.

Douglas Southall Freeman entered this world in the summer of 1910. He was twenty-four, a newspaper reporter with a Johns Hopkins doctorate earned at twenty-two, his dissertation already lost to fire. He had published one scholarly work, A Calendar of Confederate Papers.

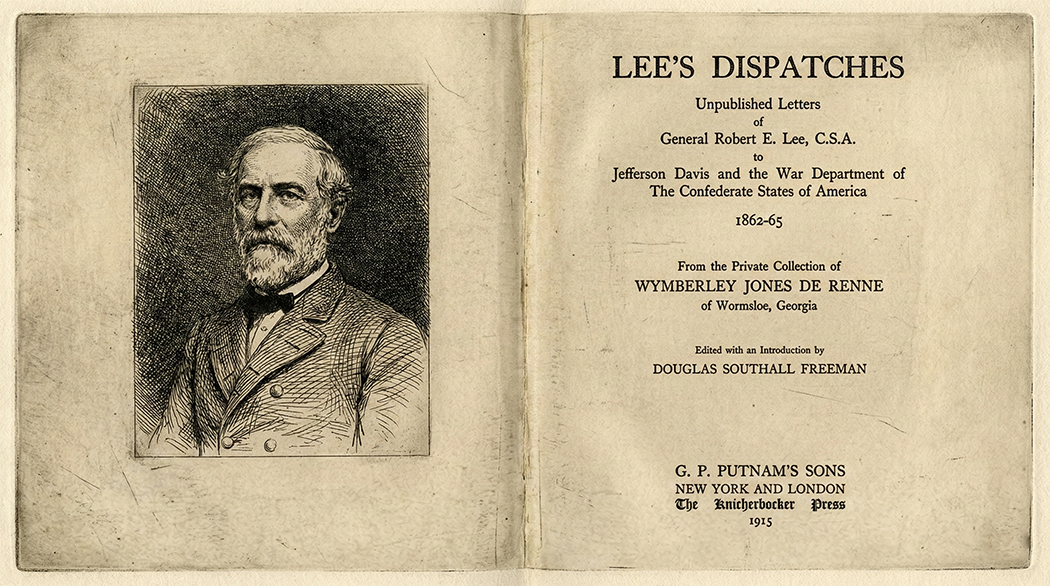

De Renne had a proposition. He owned two leather-bound volumes containing more than two hundred letters from Robert E. Lee to Jefferson Davis and the bookplate of Colonel Charles C. Jones, Jr. inside. He believed most had never been published. He wanted Freeman to examine them, edit them, annotate them, and bring them to print.

The work took four years. Freeman annotated every letter, traced every officer, verified every date. De Renne waited. He sent money. In June 1915, Lee’s Dispatches appeared—letters believed lost, missing from the Official Records, passing through a private secretary and two collectors before reaching print fifty years after the war. Freeman wanted to explain the provenance. De Renne pushed back. Freeman’s introduction identified the source only as a “well-known Southern writer.”

In 1939, Dallas D. Irvine of the National Archives published “The Fate of Confederate Archives” in the American Historical Review, concluding after years of research that Colonel Charles Colcock Jones Jr. had “purloined” the Lee dispatches. The charge was precise: Jones had acquired papers never his to keep, documents that should have been returned to Burton Harrison, surrendered to the federal government, or deposited in the archives Francis Lieber created to collect Confederate records.

Irvine’s case was circumstantial, resting largely on Harrison’s testimony that the papers had been loaned, not sold. Jones never returned them, allowing the loan to harden into possession through silence and time, until Harrison’s death in 1904 ended any claim. Douglas Southall Freeman circulated Irvine’s conclusion in The South to Posterity, even as he recognized the contradiction at its center: without Jones’s “book-madness,” the letters might not have survived at all.

De Renne did not live to see what Freeman became. He died at the Hotel Netherland on June 23, 1916. He was sixty-three. His funeral was held in the library at Wormsloe, among his treasures.

W. J. De Renne’s son inherited the library and continued adding to it until 1918. His sister contributed volumes. Leonard L. Mackall presided over the shelves from 1914 to 1931. In the spring of 1938, the family sold the Georgia collection to the University of Georgia for sixty thousand dollars, against an assessed value of two hundred and fifty thousand. They kept a few things, the rest went to Athens. The Lee dispatches did not.

Sources

Alford, Kenneth D. Civil War Museum Treasures: Outstanding Artifacts and the Stories Behind Them. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2008.

Beers, Henry Putney. The Confederacy: A Guide to the Archives of the Government of the Confederate States of America. Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, 1968. Reprint, 1986.

Books Relating to the History of Georgia in the Library of Wymberley Jones De Renne. Compiled by Oscar Wegelin. Savannah: Morning News Press, 1911.

Bragg, William Harris. De Renne: Three Generations of a Georgia Family. Wormsloe Foundation Publications, no. 21. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1999.

Bragg, William Harris. “Charles C. Jones, Jr., and the Mystery of Lee’s Lost Dispatches.” Georgia Historical Quarterly 72 (1988): 429–62.

Bragg, William Harris. “‘Our Joint Labor’: W. J. De Renne, Douglas Southall Freeman, and Lee’s Dispatches, 1910–1915.” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 97, no. 1 (January 1989): 75–100.

Burnette, O. Lawrence, Jr. Beneath the Footnote: A Guide to the Use and Preservation of American Historical Sources. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1969.

Callahan, James Morton. The Diplomatic History of the Southern Confederacy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1901.

Clark, James C. The Last Train South: The Flight of the Confederate Government. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1984.

Coulter, E. Merton. Wormsloe: Two Centuries of a Georgia Family. Wormsloe Foundation Publications, no. 1. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1955.

Freeman, Douglas Southall. A Calendar of Confederate Papers, with a Bibliography of Some Confederate Publications. Richmond: Confederate Museum, 1908.

Freeman, Douglas Southall. The South to Posterity: An Introduction to the Writing of Confederate History. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1939. Reprint, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1998, with introduction by Gary W. Gallagher.

Freeman, Douglas Southall, ed. Lee’s Dispatches: Unpublished Letters of General Robert E. Lee, C.S.A., to Jefferson Davis and the War Department of the Confederate States of America, 1862–65. From the Private Collection of Wymberley Jones De Renne, of Wormsloe, Georgia. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1915.

Freeman, Douglas Southall, and Grady McWhiney, eds. Lee’s Dispatches: Unpublished Letters of General Robert E. Lee, C.S.A., to Jefferson Davis and the War Department of the Confederate States of America, 1862–65. New Edition with Additional Dispatches and Foreword by Grady McWhiney. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1957.

Harrison, Constance Cary. Recollections Grave and Gay. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1911.

Irvine, Dallas D. “The Archive Office of the War Department: Repository of Captured Confederate Archives, 1865–1881.” Military Affairs 10, no. 2 (Spring 1946): 93–111.

Irvine, Dallas D. “The Fate of Confederate Archives.” American Historical Review 44, no. 4 (July 1939): 823–41.

Irvine, Dallas D. “The Genesis of the Official Records.” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 24, no. 2 (September 1937): 221–29.

Johnson, David E. Douglas Southall Freeman. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 2002.

Johnston, Angus James II. Virginia Railroads in the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1961.

Mackall, Leonard L. “The Wymberley Jones De Renne Georgia Library.” Georgia Historical Quarterly 2, no. 2 (June 1918): 63–86.

Patrick, Rembert W. The Fall of Richmond. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1960.

Posner, Ernst. “The Captured Confederate Records under Francis Lieber.” American Archivist 10, no. 4 (October 1946): 277–319.

Sternhell, Yael A. War on Record: The Archive and the Afterlife of the Civil War. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. 128 vols. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

Sandra Gioia Treadway and Edward D. C. Campbell Jr., eds., The Common Wealth: Treasures from the Collections of the Library of Virginia (Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia, 1997).

Patricia Spain Ward, Simon Baruch, Rebel in the Ranks of Medicine, 1840–1921 (University of Alabama Press, 1994). Bernard Mannes Baruch, Baruch: My Own Story (Holt, 1957).

Excellent work on this.

Utterly amazing and very well-written. Always glad to learn that papers and artifacts necessary for a true appreciation of history have been saved.