Three Hundred Twenty-Two Pages: Jesse Stuart at Vanderbilt

In early summer 1931, Jesse Stuart stood in the Greenup National Bank with empty pockets and a failed tobacco crop behind him. That spring he and his brother James had raised tobacco on a round knoll in W-Hollow, hoping to earn college money. Heavy rains came. The leaves went pale, then brown, then soft, then nothing. He borrowed three hundred dollars, folded one hundred thirty in his pocket, and set out.

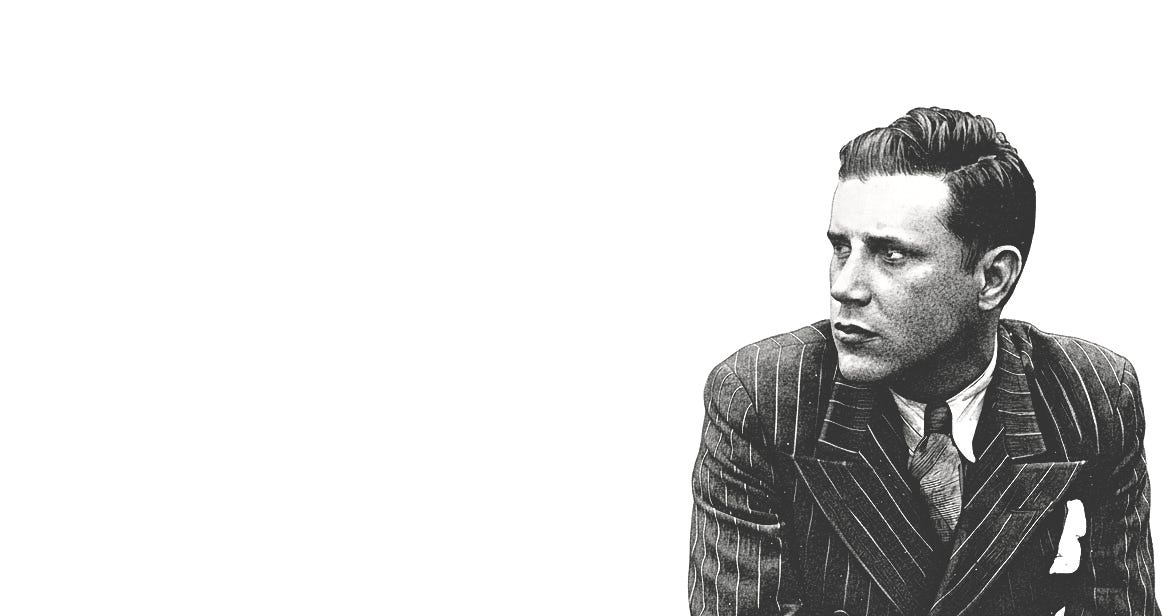

He was twenty-four, six feet tall, broad in the shoulders, hands marked by farm work and the Ashland steel mill. Family talk still ran to his great-grandfather Raphy, a six-foot-six Highlander who left the Firth of Forth with five brothers and settled by the Big Sandy.

That same summer he arrived in Nashville. The city smelled of coal smoke and river water. As O. Henry put it, “London fog mixed with gas leaks, dew drops from a brickyard, a touch of honeysuckle … not as fragrant as a mothball, not as thick as pea soup.” The streets ran straighter than back in Greenup County.

By his own account he reached Vanderbilt without ever applying. Edwin Mims listened as the young Kentuckian told his story. Mims doubted his chances but admitted him anyway. Stuart found work sweeping the corridors of Calhoun Hall, one of the few white men on that crew. He could afford eleven meals a week and counted them out like coins.

On Saturday nights he walked downtown to the Grand Ole Opry. Uncle Dave Macon and the Fruit Jar Drinkers. Dr. Humphrey Bate and his Possum Hunters. Stuart sat in the cheap seats and felt at home.

The grades came in December: three C’s and a B from Robert Penn Warren. He needed a B average for the master’s degree. “My legs weakened,” he said later.

He wrote poetry when professors assigned term papers. When he did write the papers, they missed the point. For Mims’s British literature survey he turned in an essay on Thomas Carlyle. Mims refused to accept it. Stuart reread his own prose and could not find Carlyle in it either, only three places where he had imitated the style. Another paper came back marked “Too poor to grade.”

He kept writing sonnets, notebook after notebook, and stacked them in his room beside a thesis he had started on John Fox Jr., the Kentucky writer.

In the winter of 1932, Mims assigned an autobiographical essay, eighteen typed pages due in two weeks. Stuart sat in the cold room on Twenty-First Avenue and went to work.

He wrote of the one-room school at Plum Grove and the barefoot walk through frost. He wrote of the carnival that carried him off. He wrote of the mill and the boy torn open before his eyes. He wrote of a father who could not read and a mother who had stopped in the second grade. He wrote of debt, pride, hunger. He wrote about his grandfather Mitchell Stuart, the knock-down-drag-out fighter, the hard-working, hard-drinking, land-clearing timber cutter. The man Stuart had been terrified of as a child—“If I had met Grandpa at night I would have thought he was The Devil.”

Stuart wrote for eleven days straight. Fingers cramping. Then wrote some more. He wrote like a man who had once thrown a punch for honor. When he finished, he’d written 322 pages, typed margin to margin. He knew it broke every rule. He slid the pages between cardboard, bound them tight with heavy rubber bands. He left the stack on Mims’s desk.

Professor Mims felt the weight. “There you go, Stuart. You hand me a paper like this when you are failing my class. And you know I read every word a student gives me.”

Three days later Mims called him back. His voice had softened. “I have been teaching school for forty years. I have never read anything so crudely written and yet beautiful, tremendous, and powerful as that term paper.”

He looked at Stuart. “It’s the finest paper handed to me in my career as a teacher. So crudely written and so beautiful and it needs punctuation.” He studied the boy. “If you were a son of mine I don’t know what in the world I would do with you. You’re unusual. Just some kind of special genius.”

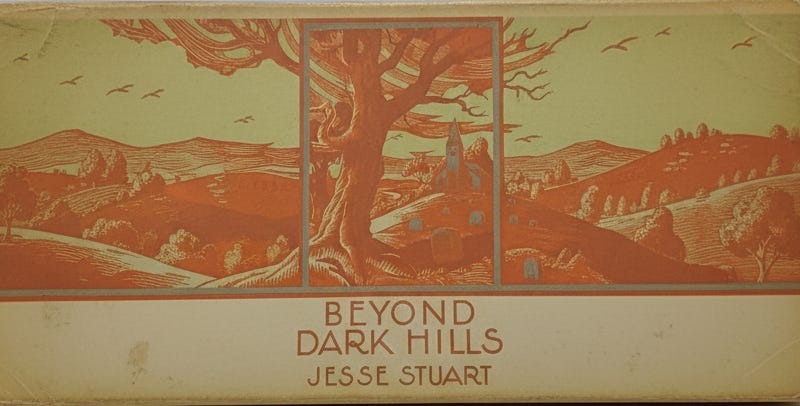

The paper earned no grade. Six years later, with a final chapter added, it became Beyond Dark Hills.

Across the hall Donald Davidson—Tennessean, poet, scholar of the ballad—taught the Elizabethan lyric. Stuart sat in the front row, first to arrive, last to leave. He brought poems from the hill-tongued and burley-barn scented. Davidson heard the true note, gave him his only A, and pointed to one called “Elegy for Mitch Stuart.”

“Send this to H. L. Mencken,” he said.

Jesse laughed. Mencken had just said no poet in America was fit to print.

“His bark is bigger than his bite,” Davidson said.

Mencken published it in The American Mercury.

That spring fire swept Wesley Hall, taking the typewriter, the thesis, the little he owned. He begged the registrar for a small loan. When the money ran out he left. He hitchhiked home on a dollar tucked in his shoe. Once he rode most of the way on a truckload of dynamite. When he could pay he took the Greyhound that rumbled across the Bluegrass toward the hills.

Before he left for good he stopped by Davidson’s office to say goodbye. The older poet fixed his compass in a sentence. “Go back to your country. Go back there and write of your people. Do not change and follow the moods of these times.”

In 1955 Greenup County named a Jesse Stuart Day. Davidson, too ill to travel, sent a letter: “You have restored the bardic tradition, the one thought lost. It couldn’t have happened to Tom Wolfe. It can’t happen to Ransom, Tate, Warren, or me.”

When Stuart’s father died, Davidson wrote again. “If from him you had the gift of life, from you he has a gift of life that mounts beyond death. As a writer, you are everybody’s memory.”

April 1968. Davidson lay dying in the hospital. He wrote Stuart a final letter. “I am putting aside all unfinished commitments and will try to get my affairs straight. We think of you with greatest affection.”

Four days later, Davidson died.

I do belong to these men of the past.

I am one of a sleeping generation.

I have gone to weed roots and dust at last.

I may not have been a builder of the nation.

But I was just one of the many millions,

Lover of earth and trees and blackberry blossoms,

And a one-horse scrap of land, Don Davidson.

- Jesse Stuart’s Man with a Bull Tongue Plow (E. P. Dutton, 1934).

Sources

Clark, Jim. “‘Unto All Generations of the Faithful Heart’: Donald Davidson, The Vanderbilt Agrarians, and Appalachian Poetry.” The Mississippi Quarterly 58, no. 2 (2005): 299–313.

Foster, Ruel E. “Jesse Stuart and Donald Davidson: A Literary Friendship.” In The Vanderbilt Tradition: Essays in Honor of Thomas Daniel Young, edited by Mark Royden Winchell, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1991.

Gifford, James M. “Donald Davidson, Jesse Stuart’s Mentor, Editor, and Friend”.

Stuart, Jesse. Beyond Dark Hills. E.P. Dutton, 1938.

Winchell, Mark Royden. Where No Flag Flies: Donald Davidson and the Southern Resistance. University of Missouri Press, 2000.

Wolfe, Charles K.. A Good-Natured Riot: The Birth of the Grand Ole Opry. Country Music Foundation Press and Vanderbilt University Press, 1999.

It has been, maybe, forty years since I read Jesse Stuart’s name. Maybe fifty years. His name resonates as a voice of common, poor, forgotten people of the land. I think of him like I do singer Jimmie Rodgers as less a writer amongst other writers, but man of a particular time and place. We think of them as separate and unique, and yet captured in time, but not for all time.

I'm on the last twenty pages of "Beyond Dark Hills." Thanks for pointing me to what easily has become my favorite book of the year.