Three Cities, One Address

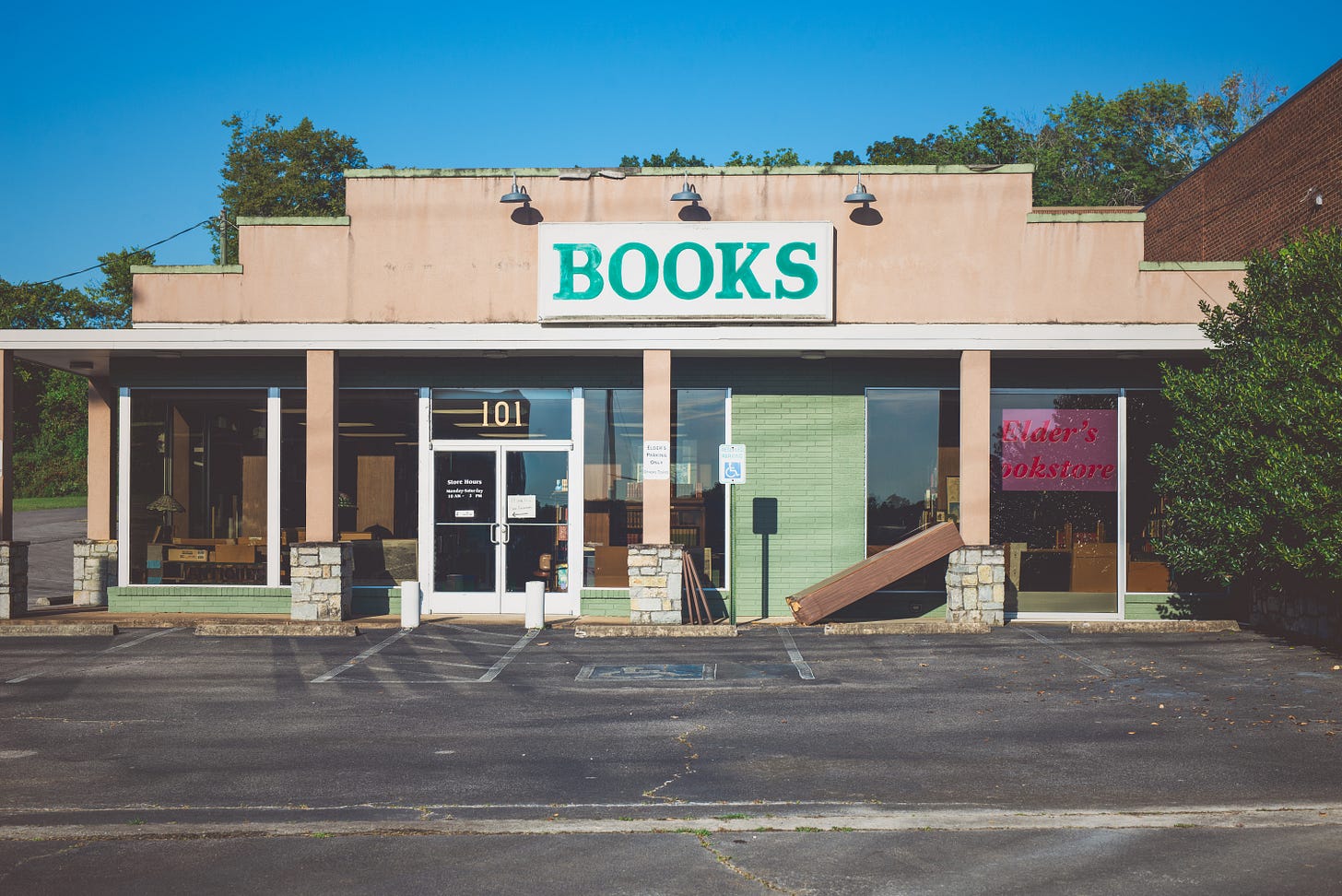

My essay “The Bookstore Time Forgot” appears in the current issue of Frontier Magazine. It tells Nashville’s story through Elder’s, Tennessee’s oldest bookstore. Randy Elder keeps it alive in a converted mattress outlet on White Bridge Road beneath a green sign that says BOOKS, nothing more, the way older generations marked graves with a single word—Father, Mother.

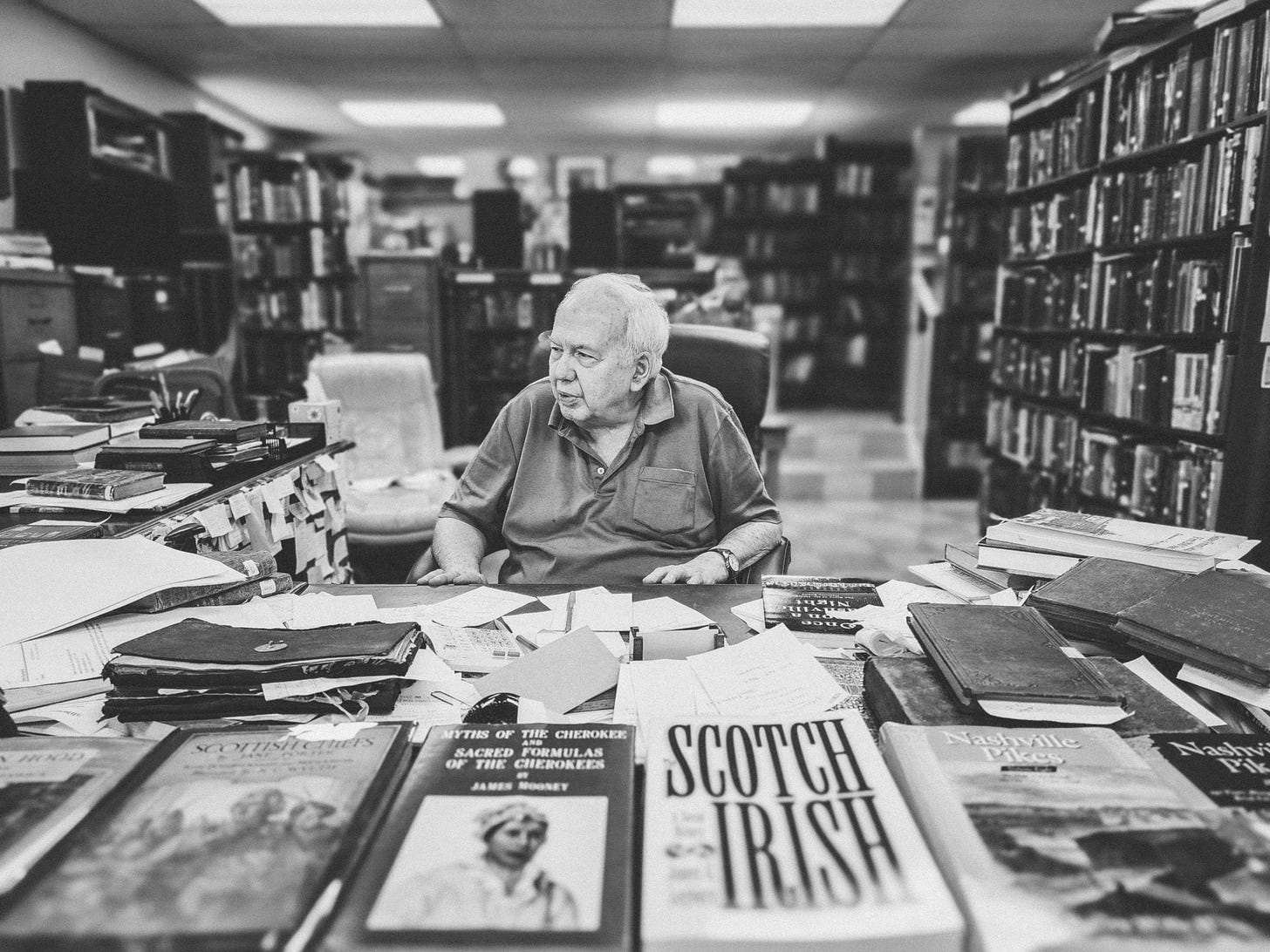

To the left, a few steps in, sits Randy Elder, the second-generation owner of the place. His desk is a Cumberland point bar where the current slows and the cultural sediment of a bookman’s trade collects. Scraps, notes, slips, and lists advance unchecked, creeping as vines will. Books crowd the edges. Cherokee myths, Scotch-Irish migrations, the roads of Nashville.

Elder’s holds the remnants of every city Nashville has been. First, Athens, when Vanderbilt men read Greek and the Fugitive poets gathered in parlors. Then Music City, when WSM carried fiddle tunes over the Tennessee hills. Now Neon Nowhere, the bright forgetting of high-rises and pedal taverns. Southern accents? Vanderbilt students speak Chinese now.

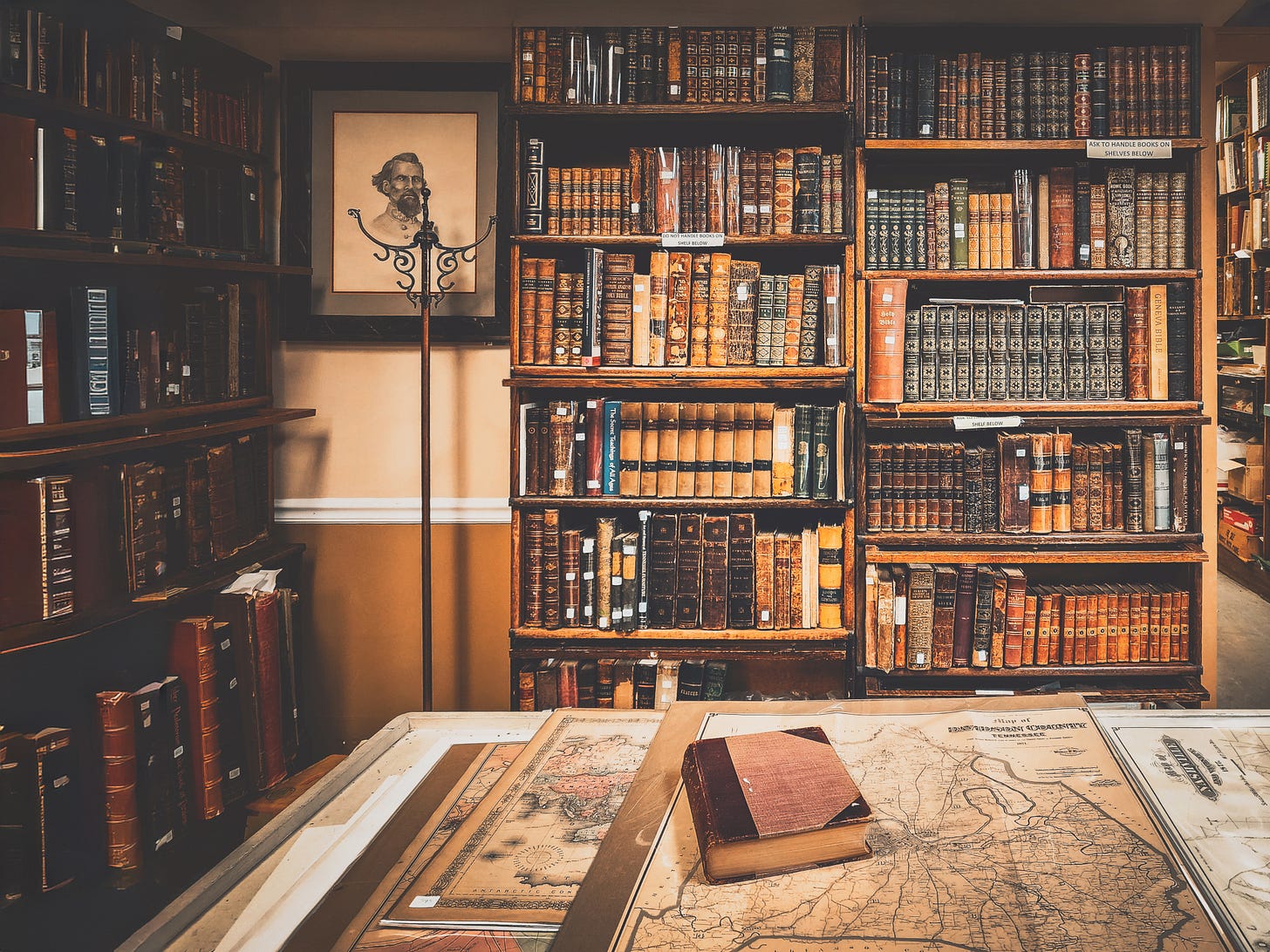

On those shelves, many threads wait to be pulled. One runs through Nashville’s literary past—the Fugitives, the Southern Agrarians—and to the generations they set in motion. Their students and their students’ students redirected the course of Southern letters. Russell Kirk read their work and found permanent things. Richard Weaver studied under them. Mel Bradford came to Vanderbilt to study with Donald Davidson. Some say the Southern Renaissance began the day Ransom walked into his first Vanderbilt classroom.

I’m hardest on the present because I live in it. The city forgets, calling its amnesia progress. We’re told to throw away old books, old ideas, old ways. But Mr. Elder remembers, selling the city back its own discarded memory. Almost twenty years ago, after I traded my DVDs for books, I walked into Elder’s on Elliston and bought my first Southern book: The Correspondence of Shelby Foote & Walker Percy.

Every city needs an Elder. A keeper who stocks Old Hickory biographies alongside hot chicken histories, who knows that the Fugitives weren’t outlaws and which singers were. State Route 155 carries me back into the stream. Behind me, the books, Randy at his desk, hands moving. Drive out there. Tell Mr. Elder you’re looking for Nashville. He’ll know which one you mean.

Mills went silent. The mule was driven out, the tractor drove in. Nashville was not spared the change. In 1930, Charles Elder opened a bookstore downtown. That year, Twelve Southerners set their names to a book, their defense against a world given to the machine. You can find I’ll Take My Stand now on Elder’s shelf, between The Fugitive and Who Owns America?.

Beyond the desk stands the table, the center of the room. Glass-topped, its map spread wide, rivers like veins, counties etched in brown. Rolled maps jammed beneath like artillery shells. Over it all, the General’s portrait hangs—bearded, stern, eyes that follow; the patriarch of the room.

There are still Athenians about. You can find them over on the West End, where even the mosquitoes are more blue-blooded than my people.

Love that your first was Foote and Percy's letters. Haven't read all of them, but one of my favorites was where Foote wrote Percy, "Have you ever been tempted to just run away from your wife and off to the South Pacific with two co-eds?" Apparently the gray eminence of Southern history had a hard time hanging on to marital bliss.

Many, many purchases there over the years, my first copy of I’ll Take My Stand and Paul Conkin’s book on the Agrarians among them.

Underappreciated, too, is Elder’s large collection of Church of Christ/Disciples of Christ literature. I found a near flawless first edition of William Baxter’s Life of Elder Walter Scott there many years ago.