The Folk-Chain of Memory

Donald Davidson first wrote “folk-chain” in his 1927 poem “Hermitage,” and later spoke of the “folk-chain of memory” in his 1966 lecture “The Center That Holds: Southern Literature & The Oldtime Religion.” These words had to wait another eighteen years before finding their way into print in Southern Partisan magazine in 1984.

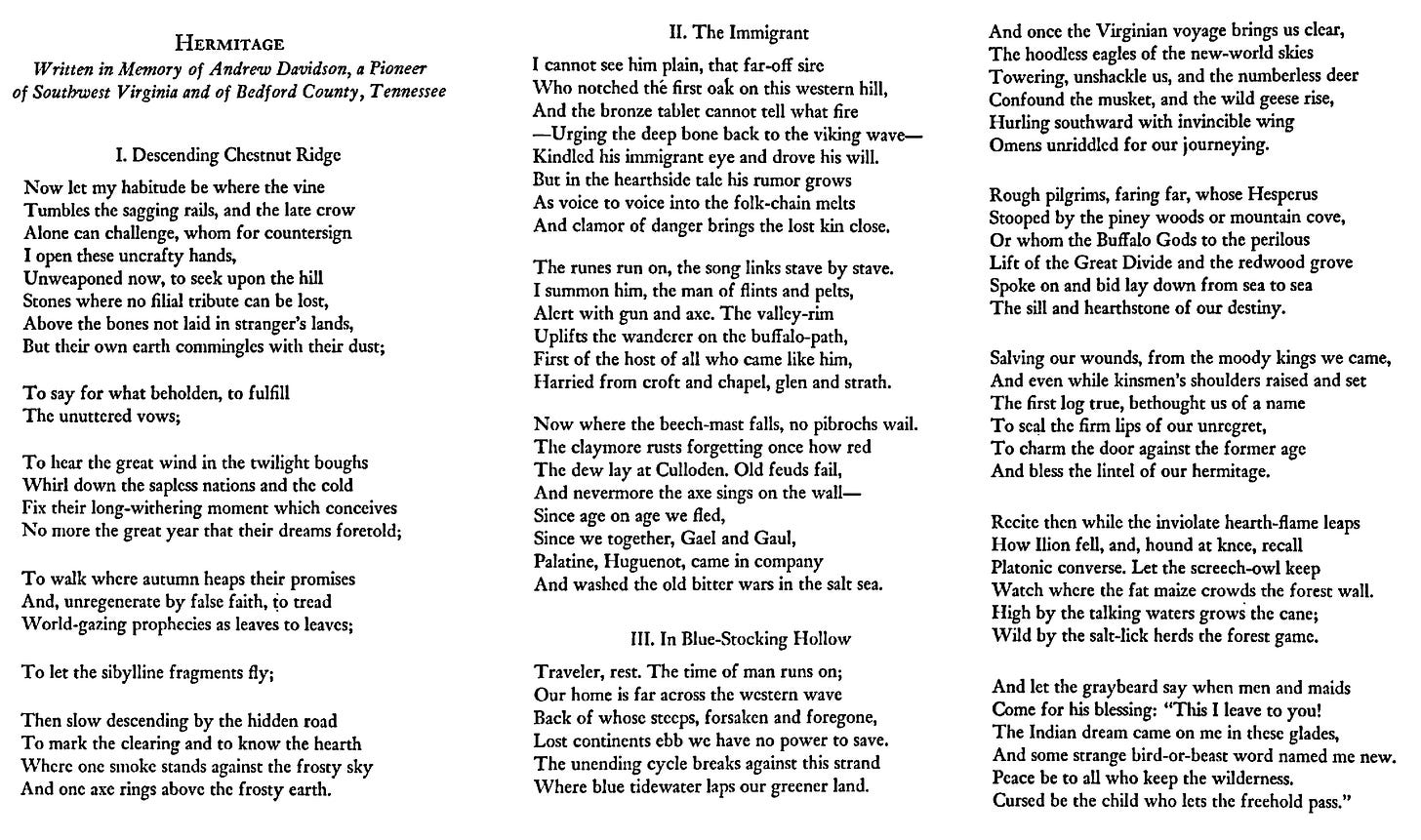

The Poem

Memory Older Than the Rememberer

In “Hermitage,” Donald Davidson knew memory was something older than remembrance, deeper than nostalgia. The modern mind, obsessed with self, treats memory as a private affair, locked in the vault of “lived experience.” Davidson knew better and what men forget. How memory passes not through books but through blood. Through hands that work the same soil across generations. Through family reunions at state parks. It lives in the way Grandfathers teach boys to read tomorrow’s rain in today’s clouds, in the recipes never written down, in voices rising from porch swings as the sun surrenders.

This memory he writes of dwells beyond the sanctioned narratives of consensus historians. The folk-chain he called it. Not history written by the victors but memory carried by the survivors. The South Davidson knew lived by this chain of memory, each generation taking hold of the links forged by their forebears, shaping a new one, and passing it down.

The poem remembers what Davidson knew. That we are what we remember together as a people, by how the soil itself keeps account of our passing, and by our willingness to accept the inheritance of those memories. That some truths can only be told in the telling and retelling. His poem becomes not merely words but a sacred trust. Memory older than the rememberer.

Headstones, Husk Lands, and Hearths

When Davidson sets foot on Chestnut Ridge, he’s treading not just soil but stories. He came down off that ridge where his people’s story waits. See how he marks where vines claim the rails men split and stacked, the borderlands between what man built and what God reclaims.

When he seeks out those gravemarkers—“Stones where no filial tribute can be lost / Above the bones not laid in stranger’s lands”—he is not merely paying respects but establishing coordinates in the geography of belonging.

Those lines, “To say for what beholden, to fulfill / The unuttered vows,” carry Burke's understanding that history is not some academic abstraction but a living compact, joining those dusty earth comminglers, the living, and those not yet quickened in the womb. Russell Kirk was fond of citing Burke on this point—without these obligations, “generation will not link with generation, and men will be as the flies of a summer”—creatures without memory or meaning.

He left “sapless nations”. The husk lands. Blood transfusion won’t take. Their veins collapsed long ago. In contrast, Davidson transports us to the hearth, the lifeblood of traditional life, the center that M.E. Bradford called “the homely and routine operation of tradition.” Just the everyday done every day. The fire tended. The wood split. The bread baked. Small acts. Ancient acts.

Davidson knew where the true chain holds. Places where “one person teaching another extends the folk-chain.” As he wrote, “What passes from memory to memory, without benefit of the historian’s record, is as old in time as the memories that it expresses, and if it is accepted it endures as long as the land and people that accept it.”

There Are Portals

The title “Hermitage” carries layers of meaning. Davidson names directly the homestead of Andrew Davidson, but deeper still it evokes a hallowed ground where a man can sit quiet and hear the voices of his fathers. The Hermitage becomes both the dirt under your feet and a sanctuary. A sanctuary against forgetting. Against the sickness of a world that knows no yesterday and sees no tomorrow.

“Hermitage” stands against our newfangled notion that time marches one way toward some brighter tomorrow. Instead, it offers what Anthony Harrigan named “transcendent memory”—that sacred knowing that lets us move through portals.

The second section calls forth “the man of flints and pelts,” revealing this memory-magic at work. Though long dead, blurred by decades, this ancestral presence manifests through the “hearthside tale” where “voice to voice into the folk-chain melts.” This poetic alchemy demonstrates Davidson’s faith that through “communion and pietas,” reverence conquers the tyranny of passing years. In the New World, Scottish bagpipes fall silent and swords tarnish, as former foes—”Gael and Gaul, Palatine, Huguenot”—arrive together, their blood feuds washed in the Atlantic crossing.

Can the Folk-Chain Be Unbroken

The poem closes with an elder’s double-edged pronouncement: “Peace be to all who keep the wilderness. / Cursed be the child who lets the freehold pass.” Through these twin utterances, Davidson crafts a stewardship covenant between generations, which he understood as more than caretaking of physical land. It is also the vigilant tending of memory itself.

As Bradford wrote, our obligation is to “cultivate the arts of memory, and thus hope to preserve to our posterity the bond” that links generations. Davidson’s poem serves both as demonstration and invitation, showing how one might maintain the folk-chain while inviting readers to make similar journeys of remembrance.

The Center That Holds

I’ve written enough, here’s Davidson’s exposition on the folk-chain in “The Center That Holds”:

A section of The Tall Men—which I first published in 1927—is by this measure about a hundred years old, for it embodies what my grandmother told me—my grandmother who was a girl in her late teens, in Chapel Hill, Tennessee, during the Federal occupation of the eighteen-sixties. She saw her young friends, Confederate soldiers in uniform, captured and shot down in cold blood by Federal troopers. She saw them lined up by the roadside, and the rifles levelled. She heard the shots and saw them fall—all but one who broke away and ran—and then was shot, too. She helped “lay out” the bodies for burial. And she told me about it one day when I was a child at her home. Later, when I was endeavoring to define, in a series of long poems, the relationship of a modern Southerner to his past, I remembered what my grandmother had told me and made it part of a poem (“The Sod of Battlefields,” in The Tall Men).

All of us in the South do a great deal of this kind of remembering, within the circle of family and close friends. With a little help from written records—family papers, books, all that we somehow accumulate—we project our memories far back. In another poem of mine (“Hermitage”), in which I try to visualize a colonial ancestor, I deal with this process of memory:

I cannot see him plain, that far-off sire Who notched the first oak on this western hill. And the bronze tablet cannot tell what fire -Urging the deep bone back to the viking wave- Kindled his immigrant eye and drove his will. But in the hearthside tale his rumor grows As voice to voice into the folk-chain melts And clamor of danger brings the lost kin close.

To see how the folk-chain of memory binds us together and comes into dramatic being in story or novel at some unexpected moment, I would offer Andrew Lytle’s novel The Long Night as a distinguished example.

If in this new Reconstruction that we are now enduring, a hundred years after the first, we should accept and apply the advice being given by the new apostles of discontinuity and destruction, we shall have no more writers like Faulkner, Tate, Cabell, Glasgow, Warren, Ransom, Katherine Anne Porter (to name but a few); but our novelists will be the fiction-writing parallels of Ralph McGill and Harry Ashmore, and our poets of some new Beatnik school will be practicing their Southern versions of Howl.

Instead of such degeneration, we have come—as I said back in 1950—“to the moment of self-consciousness . . . the moment when a writer awakes to realize what he and his people truly are, in comparison with what they are being urged to become.” And what does this mean? It means that the Southerner (or any other member of a traditional society, even a fragment of one) does not have to labor to learn some things. We already know, from the start, who we are, where we are, where we belong, what we live by, what we live for. That priceless inheritance is something given to us. But in the thoroughly modernized, anti-traditional society, it is not given; it can be achieved, if at all, only after long struggle. It is exactly what the apostles of the new Reconstruction, in the pseudoscientific language of the modern power-state, are saying we must not have, must give up if we do have it.

But we have not given it up. And so our moments of self-consciousness may become moments of deepest remembrance that lead to the life of the imagination—the poem, the story, the play, the novel. Yet the writer’s imagination only brings into significant form the life of our people who have cherished, through long tradition and rich custom, what makes such imagination possible. In 1903 the great Irish writer, William Butler Yeats, wrote this of the people of the Galway plains:

There is still in truth upon these great level plains a people, a community bound together by imaginative possessions, by poems and stories which have grown out of its own life, and by a past of great passions which can still waken the heart to imaginative action. One could still, if one had the genius, and had been born Irish, write for these people plays and poems like those of Greece... England or any other country which takes its tunes from the great cities and gets its taste from schools and not from old custom, may have a mob, but it cannot have a people... A people alone are a great river, and where a people has died, a nation is about to die. (The Galway Plains)

So said Yeats, and what he said came true for Ireland and for William Butler Yeats. Between the Ireland of Yeats and the South of the past three or four decades, there is, I would say, a stirring likeness. We, too, have been and still are a community bound together by imaginative possessions—a people that has not yet died, a community that, though shaken, battered, and maimed, still lives as a community. What binds us together is, in some considerable measure, what bound the Irish people through the centuries. I remember the very words of the Irish poet George William Russell (Æ), a friend of Yeats, when he stood before a Nashville audience many years ago—the ladies of the Centennial Club and their guests who had come together to surprise Russell with a birthday celebration in his honor. “I will tell you,” said he (in a fine impromptu speech after the presentation of the birthday cake), “why Ireland has a great literature. Because we were poor; because we were backward; because we were downtrodden and oppressed; because we loved our country; because we were religious.” And, hearing that beloved poet as he towered before us with his great brown beard and mighty shoulders, I felt then as I feel now, that he might be speaking for Tennessee, for Virginia, for all the besieged, invaded South, no less than for County Sligo, the River Shannon, Dublin, Tara’s halls.

Notes

I’m not saying anything new, just wanted to share Davidson’s poem and essay.

My sources:

Bradford, M.E. “Donald Davidson and the Calculus of Memory.” Chronicles, 1994-05.

Davidson, Donald. “The Center That Holds.” Southern Partisan 4 (Fall 1984): 17-22. Also published in So Good a Cause: A Decade of the Southern Partisan.

Davidson, Donald. The Long Street: Poems. Vanderbilt University Press, 1961.

Harrigan, Anthony. “Transcendent Memory.” Chronicles, 1987-07.

Kirk, Russell. The Essential Russell Kirk: Selected Essays. Intercollegiate Studies Institute, 2014.

Pratt, William. “Donald Davidson: The Poet as Storyteller.” The Sewanee Review 110, no. 3 (2002): 406–25.

Winchell, Mark Royden. Where No Flag Flies: Donald Davidson and the Southern Resistance. University of Missouri Press, 2000.

"Peace be to all who keep the wilderness / Cursed be the child who lets the freehold pass."

That hits hard.