It Costs Us Nothing: Post-War Consensus University Press

In Orvin Lee Shiflett’s William Terry Couch and the Politics of Academic Publishing: An Editor’s Career as Lightning Rod for Controversy, there’s a reference to It Costs Us Nothing, a 1948 pamphlet by W. T. Couch. Naturally, I found a copy, finding its arguments unexpected yet relevant to much of our current siloed digital discourse regarding state propaganda, narrative, and consensus. Commentary on it is sparse: a 1948 Washington Post letter, a brief note by Marion Montgomery, and Shiflett’s analysis. Montgomery and Shiflett are worth quoting on the topic:

Marion Montgomery’s editorial note in Modern Age introducing “Regionalism” by Donald Davidson mentions the pamphlet, Montgomery writes:

In the summer of 1982, I wrote William T. Couch, a name familiar to the readers of Modern Age, asking him about the publishing history of Donald Davidson’s The Attack on Leviathan (1938). Couch published the book while Director of the University of North Carolina Press. He went from there to direct the University of Chicago Press, just as World War II was winding down. From Chicago, he became editor-in-chief of Collier’s Encyclopedia, in the early 1950s. My inquiry prompted a number of detailed letters from Couch, retired to Chapel Hill, the letters centering especially on the very active censorship exercised by the political left, especially through its control of the American Library Association. He had opposed that bias, at cost to him. It is a sordid episode, this attempt by the left to determine what is and is not suitable for citizens to read. The media, of course, are much more interested in the attempt by some Fundamentalist mother in Tennessee or Georgia or West Virginia who is trying to have a scrofulous novel or evolutionist textbook removed from a rural high school than in the behind-the-scenes attempt to prevent F. A. Hayek’s Road to Serfdom (1944) from reaching a wider audience.

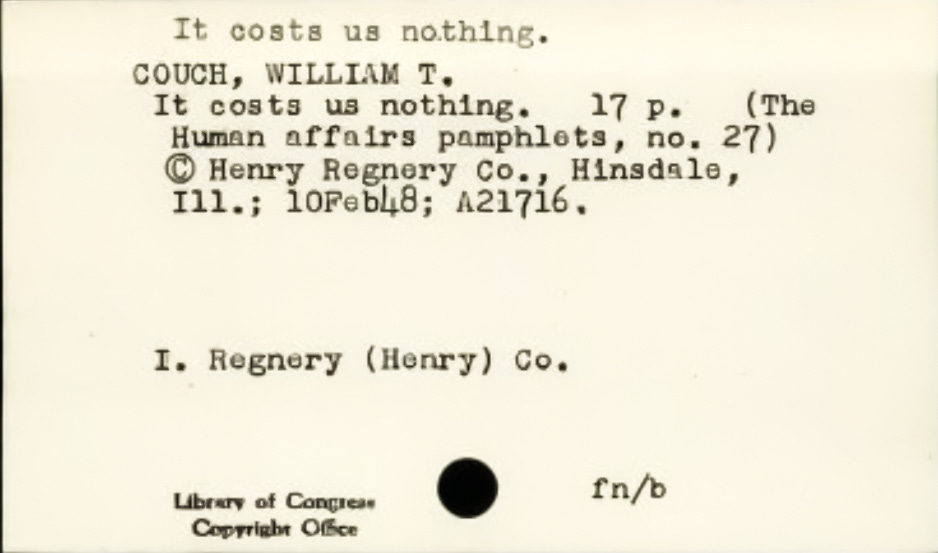

Couch spoke out on such censorship from his increasingly embattled position. The Hayek episode, among others, is recorded in his “Sainted Book Burners” (The Freeman, April 1955), and the role of the American Library Association as pre-publication censor is revealed there. He had already published, with Henry Regnery in 1948, a booklet on the subject, It Costs Us Nothing.

These pieces, and his letters to me, show a complicated and important topic yet to be sufficiently detailed. The theme might well be the left’s “protective censorship” that has influenced the climate of our political and social thought since World War II. Such a book might well begin with Couch’s struggles with President Robert Maynard Hutchins and his administration at the University of Chicago when Couch was director of that press. The attempt was made by the administration there to prevent the publication of a book containing words embarrassing to the political left, words about Justice Warren’s role in the imprisonment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

The book was at last published, but Couch’s firm stand in the matter cost him his job, though as usual in such matters the public grounds of dismissal were quite different from the buried reasons. There is a book waiting here, then, one which will show heroic attempts by Couch, Henry Regnery, Russell Kirk, and others who were fighting important battles now largely forgotten in a war that continues.

Shiflett says Couch, fed up with Publishers Weekly ignoring his letters and feining ignorance, went to Regnery. That’s how It Costs Us Nothing came to be. Shiflett:

[Couch] had become increasingly infuriated over the collusion between American book trade associations and the United States Department of State that resulted in the incorporation of the United States International Book Association (USIBA) as a non-profit corporation in 1945. The USIBA was a consortium of 145 publishers at its peak membership led by Chester Kerr, head of the Book Division of the United States Office of War Information. For American publishers, the major object of the USIBA was to promote the sale of American books abroad. For the Department of State, the object was to promote American ideals and the spread of American democracy throughout the world. By late 1946, the two objectives were at odds. The State Department put its efforts into elaborate and expensive book shows abroad to bring favored books to the attention of foreign booksellers and an international reading public to the detriment of American publishers interested in opening foreign markets to all the books they produced. American publishers and their trade associations were more interested in expanding international markets for all American books than advertising America by singling out books that promoted American values and United States policies to a world devastated by war. This dissention was fatal and the USIBA was terminated at the end of 1946.

Couch was upset with the USIBA and its tactics, but equally upset with the American Book Publishers Council for lobbying Congress for special treatment. He refused to “have any part whatsoever in any effort to secure support from the Department of State or any other agency of the Federal Government in the effort to get foreign markets for books or anything else.” His particular target was the intimate relationship that he found “thoroughly pernicious between the publishers associations and the U.S. Department of State to develop foreign markets.” The lobbying activities carried on by the publishers associations to influence federal legislation particularly concerned Couch. He was enraged about a proposal from the State Department that would require countries accepting loans from the United States to rebuild after the war to commit part of the money to purchasing books from American publishers through the Marshall Plan.” He was furious over a proposed requirement that publishers submit books to UNESCO to evaluate their “treatment of other nations.” This was pure censorship. The other provisions were simple cultural imperialism. If other countries really wanted American books, they could use the loans to purchase them without being required to do so as a condition for the loans. The efforts of the publishing associations abetted by the State Department were a move toward centralization and statism that were anathema to Couch.

So, here you go:

For the Curious

“An American Publishers’ Group Reports on German, Austrian Book Publishing” Publishers Weekly 155.15, 1949-04-09.

“Books in World Rehabilitation” Congressional Record, Senate 1948-05-25

“Foreign Markets for United States Books” Publishers Weekly 148, September 1, 1945.

“Money Needed by Europe to Implement Marshall Plan” Publishers Weekly 152.14, 1947-10-04.

“The Industry Reports to the Government on Books in World Rehabilitation” Publishers Weekly 153.18, 1948-05-01.

All of the above can be found here.

Books as Weapons: Propaganda, Publishing, and the Battle for Global Markets in the Era of World War II by John B. Hench, Cornell University Press, 2010. (Amazon link)

American Textbook Publishers Institute, Books in World Rehabilitation: A Memorandum for Members of the Congress of the United States, Department of State, Department of the Army, Department of Commerce (1948), (Just purchased in order to archive it.)

Related

Looking at the post-war era, one would be tempted to think that in some cases victory, indeed, ruins.

It is really an interesting time. We are just now getting to the point of where we can see it clearly.